Two years on: Myanmar's enduring post-coup conflict

As the second anniversary of the military coup in Myanmar passes, and military rule prevails, there are few signs that a return to democracy is likely. The security situation in the country has only deteriorated, with resistance groups like the People’s Defence Force (PDF) launching localised insurgencies against military (Tatmadaw) targets in several parts of the country, and escalating attacks in Yangon. Amid challenges to both sides’ respective capabilities a stalemate persists, and any decisive resolution to the conflict seems elusive.

BETWEEN DEMOCRACY AND MILITARY RULE

In recent years, the National League for Democracy (NLD), Myanmar’s most successful political party, had made significant democratic gains. The NLD had secured comprehensive victories in the 2015 and 2020 general elections and Myanmar’s fledgling democracy showed signs of consolidation. By late 2020, NLD leader Aung San Suu Kyi was widely popular and the NLD’s electoral victory had secured a popular mandate for substantial democratic reform.

Yet, with Myanmar’s 2008 Constitution guaranteeing the Tatmadaw 25 percent of parliamentary seats – and control over key institutions such as the Ministry of Defence and the National Defence and Security Council – Myanmar’s ability to transition to democracy was always going to be limited. Despite this, although the constitution ensured that the military’s role in politics was secure, the NLD’s landslide victory was a clear threat to its authority. Eager to stay in power, the military launched a coup against Aung San Suu Kyi’s government in February 2021. Thousands took to the streets in protest, but as the days and weeks passed and as the Tatmadaw stood unwavering, many protesters took up arms.

BUILDING RESISTANCE: SUCCESS AND CHALLENGES

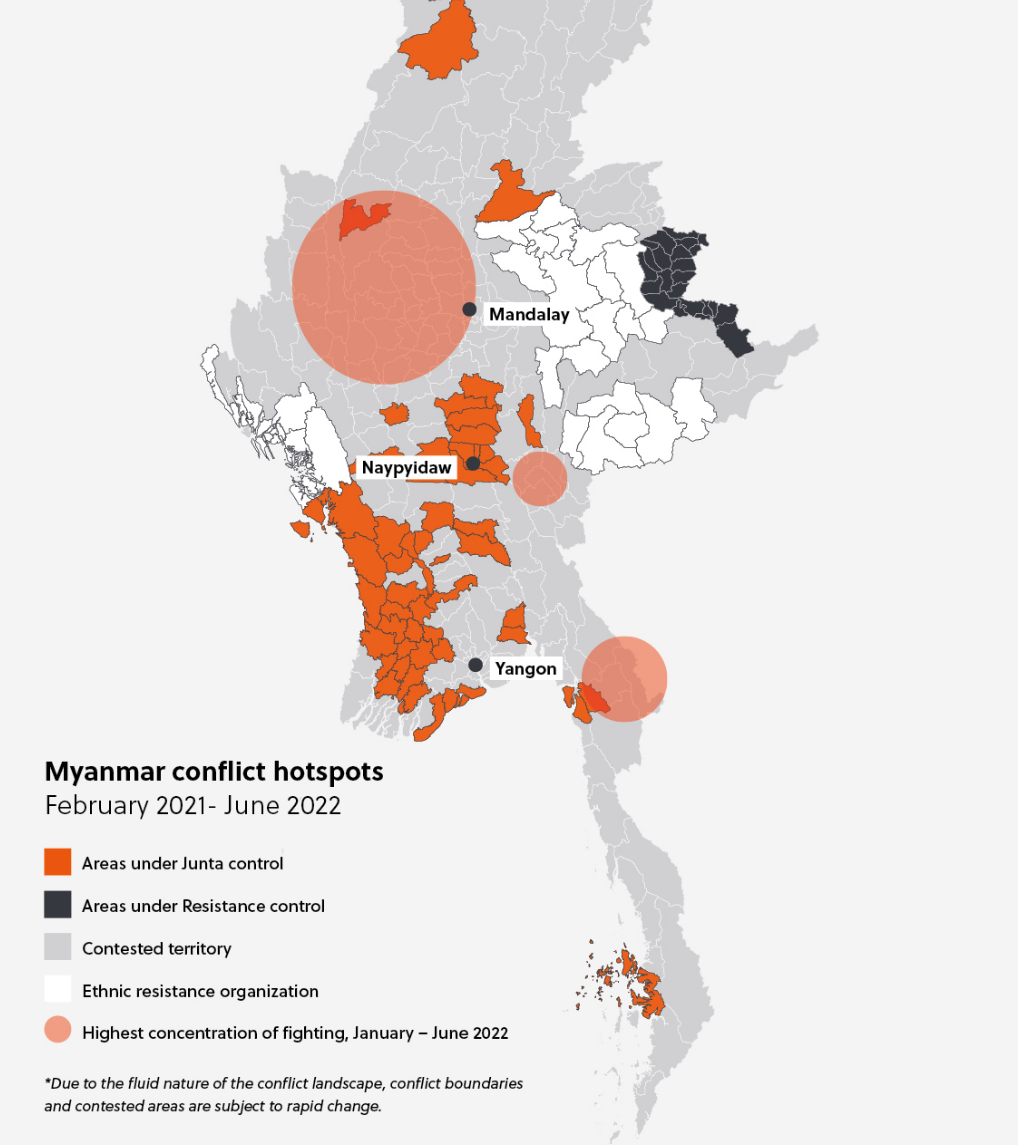

Since the coup, the anti-junta movement has faced severe military crackdowns, with over 2,500 people killed and 16,500 arrested during anti-coup demonstrations. Despite this, the movement has remained resilient, with various resistance groups united against the Tatmadaw’s airstrikes on civilian targets and alleged torture of civilians. The PDF – the armed wing of the shadow civilian National Unity Government (NUG) – has become an increasingly organised force of over 65,000 troops and 250 units operating in several parts of the country, across the northeast, northwest and southwest regions. In some cases, they have further managed to advance into military-held territory, including Mandalay.

These resistance efforts have also re-energised Myanmar’s ethnic armed organisations (EAOs), many of which had waged insurgencies against previous regimes, bolstering the anti-junta movement’s numbers and geographical reach. Battlefield experience among some EAOs, such as the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), has further boosted the movement’s fighting capabilities. Estimates indicate that 220 out of Myanmar’s 330 townships are now heavily contested, and up to 50 percent of the country is under control of various resistance groups. The PDF and urban guerrilla groups have also increased the frequency of attacks in urban centres, such as Yangon, with 121 bombings staged in the commercial hub over the last two years.

The movement still faces significant challenges, including funding issues and a lack of access to resources. The PDF relies entirely on donations, sometimes in the form of online crowdfunding campaigns, and receives weapons from neighbouring countries through underground networks. Meanwhile, the junta’s restrictions on the movement of money have stymied the resistance’s ability to mount higher-impact offensives. The PDF, allied EAOs, and the populations among whom they operate, also remain vulnerable to the military’s increased use of airstrikes and artillery fire; over 150 civilians were killed in strikes in between October 2021 and September 2022 while the conflict has resulted in significant damage to infrastructure. As the conflict drags on, the PDF and EAOs risk losing further resources and resolve.

Alliances between the various anti-junta groups are also increasingly fragile. While the PDF and EAOs have coordinated their campaigns against the Tatmadaw to an extent, decentralisation and myriad ethnic and religious agendas spread across a vast geography have impeded coordination. This has made building a cohesive strategy against the military difficult to achieve, particularly as trust between the PDF and EAOs – many of which are themselves rivals – is absent. And, even with unlikely prospects of a negotiated resolution, the number of stakeholders and their diverse interests will make securing an enduring peace deal challenging.

THE JUNTA'S HEADACHE

Simultaneously, although the Junta has been able to maintain control over most population centres like Mandalay and Yangon, it too is facing mounting challenges. The Tatmadaw has been shunned by much of the international community, with Western sanctions leading major multinational energy corporations, such as TotalEnergies and Chevron, to cease operations in the country. Capital flight has only deepened the cost-of-living crisis and further fuelled anti-junta sentiment. Additionally, the Tatmadaw has struggled to attract new recruits, and many personnel have either defected or deserted. This has prompted an increased reliance on airstrikes, using equipment supplied by Russia and its few remaining international partners. Though militarily better resourced than the PDF and its allies, the Tatmadaw’s steady supply of weapon shipments from Russia is in danger of decline amid Russia’s own armament struggles in the ongoing war in Ukraine.

Despite these challenges, the junta has remained steadfast in its efforts to stay in power. The junta’s plans to hold elections when the current state of emergency ends later in 2023 are widely seen as paying lip service to calls to return to democracy and a means to appease Myanmar’s Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) neighbours. However, elections under the current climate will do little to deescalate the grievances of the PDF and will likely only drive further resistance efforts.