Pledges and Pressures: Unpacking the 2025 NATO Summit

The June 2025 NATO summit in The Hague will be remembered for the bold pledge by member states to raise defence spending to five percent of their respective GDP’s and up from the current two percent target, amid growing US pressure for more equitable burden sharing. While this marks a step toward enhancing NATO’s overall capabilities and self-reliance – particularly among European members – the summit’s focus on reaffirming unity nevertheless leaves several critical issues unresolved. Chief among these is the lack of a unified strategy to counter growing Russian aggression in Europe, ongoing uncertainty over the long-term presence of US forces in the region, and the considerable difficulty many European countries will face in meeting the new spending goal. These challenges also reflect a deeper lack of cohesion within the alliance, hindering strategic clarity and unity of purpose at a time when NATO is confronting some of its most serious threats since the end of the Cold War.

The Russian conundrum

Russia’s slow but steady gains in Ukraine, combined with NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte’s June warning that Moscow could be capable of attacking a NATO member within five years, have heightened security concerns across the alliance. As a result, developing a coherent strategy to counter Russia’s military, political, and hybrid warfare threats emerged as a key priority at the 2024 summit in Washington, DC. But, despite signalling intent to move towards a longer-term, coordinated strategy – and committing to presenting recommendations for this at the 2025 summit – no such framework was announced at the recent gathering. In fact, the issue was deliberately omitted to avoid public disagreements between member states, highlighting persistent divisions within the alliance.

These divisions lie primarily between the US, Canada, and European members over how to assess and respond to Russia’s strategic and military ambitions. While many European leaders have called for tougher sanctions on Moscow, US Secretary of State Marco Rubio warned that increased pressure could push Russia further from the negotiating table. Since the summit, President Donald Trump has hardened his stance, threatening in July 2025 to impose secondary tariffs on countries that continue trading with Russia if no peace deal is reached with Ukraine by early September. Yet these moves remain largely unilateral and fall short of a unified, alliance-wide response, offering little reassurance to European leaders - especially those on the eastern flank who are most exposed to the risk of Russian aggression.

Russia’s slow but steady gains in Ukraine, combined with NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte’s June warning that Moscow could be capable of attacking a NATO member within five years, have heightened security concerns across the alliance.

A US drawdown?

In addition, uncertainty surrounding the future of the US military presence in Europe remains largely unresolved. Central to any credible deterrent against a potential Russian attack on a NATO member is the assurance that the US – with its unmatched military capabilities – would lead the alliance’s defence. Yet, in the early months of his presidency, Trump suggested he might not defend NATO members that failed to meet their defence spending obligations. With his recent statement at the summit indicating that US commitment to NATO and its collective defence is “ironclad,” the lack of certainty around whether this commitment will remain conditional on meeting the agreed spending goals remains a source of concern in European capitals.

In recent months, the US has also repeatedly signalled a shift in strategic focus toward the Indo-Pacific. The outcome of the June summit offered little clarity on this direction, with further details expected following a Pentagon review of current deployments later in 2025. European NATO members increasingly expect a reduction in US forces in the region and are already preparing scenarios that may involve the withdrawal of between 10,000 and 20,000 of the roughly 80,000 US troops currently stationed on the continent. Remaining US forces would take on more of a support role, requiring European members to assume greater responsibility for frontline defence. European officials have expressed concern over the alleged limited communication from Washington regarding the timeline and nature of any withdrawal, which complicates efforts to bridge potentially significant shortfalls in European defence capabilities during such a transition.

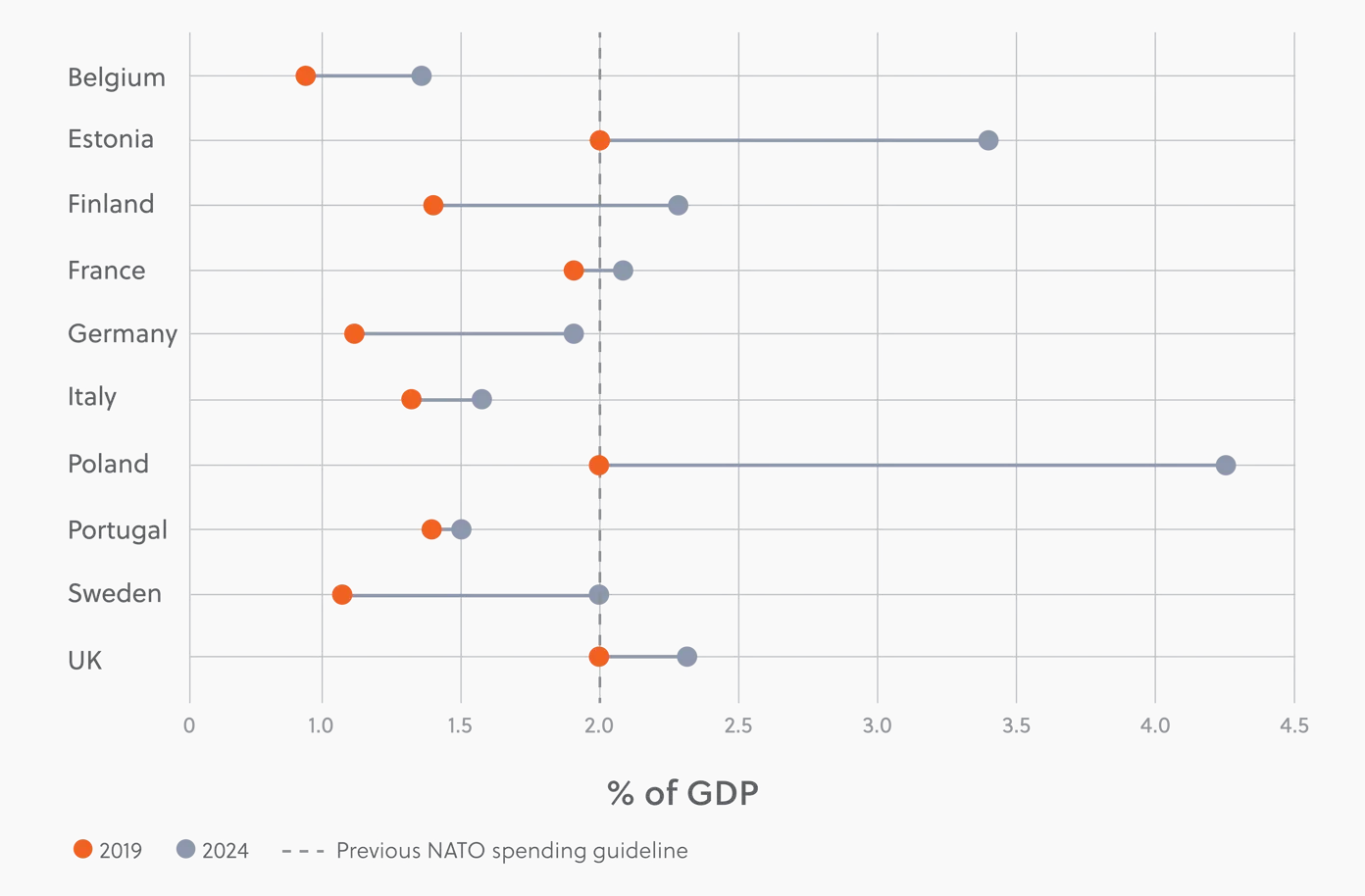

NATO defence spending as share of GDP: 2019-2024

Continental challenges

The growing Russian threat and lingering uncertainty over the long-term US military posture in Europe have been key drivers of agreement among European NATO members to increase defence spending. With the exception of Spain, which secured a last-minute exemption, all NATO members have pledged to meet the new spending targets by 2035. Under these targets, 3.5 percent of GDP will go toward core defence, including on military assets such as equipment, and 1.5 percent toward non-military defence-related areas, such as strengthening the resilience of critical infrastructure.

Yet, this display of political will is likely to face significant challenges on the domestic front in the years ahead. Many European NATO members continue to grapple with economic pressures and public pushback; Italy and Belgium, for example, have struggled to meet the previous 2 percent target, while growing defence budgets had already sparked unrest across Europe even before the 5 percent target was agreed, particularly in countries burdened by high levels of public debt. In April 2025, tens of thousands protested in Rome, demanding that funds allocated to defence instead be directed toward improving the country’s struggling healthcare and education systems. Similar protests have taken place in other member states, including Belgium, the Netherlands, and Spain, suggesting further hikes will be met with growing discontent.

With the possibility of a Russian attack on a NATO member within the next decade, the urgency of building a robust European defence-industrial base is clear. However, a sharp increase in defence spending does not automatically translate into greater military capability, and any significant improvement in reducing reliance on the US will likely take years. Fragmentation across European militaries continues to hinder integration efforts, and national priorities still dominate procurement decisions, leading to incompatible weapons systems, overlapping projects, and fractured supply chains. For example, European armies currently operate 12 different models of main battle tanks, and multiple variants of artillery systems. To boost interoperability, European allies will need to develop a coordinated strategy focused on multinational projects and joint procurement, ensuring that increased spending results in sustainable and effective military strength. Yet so far, there has been little meaningful progress toward achieving this.

Unanswered questions

Despite the historic pledge to raise defence spending, the summit concluded with more questions than answers. The final declaration was notably brief and vague, offering little in the way of a concrete strategy, or a clear agenda for the 2026 summit. Much will depend on the trajectory of regional geopolitical developments and key relationships over the next year – such as the US administration’s foreign policy stance, Putin’s strategic calculations, and whether European member states are willing and able to remain committed to their spending goals. All of this leaves Europe’s security landscape, and the future and effectiveness of NATO as a collective defence pact, on uncertain ground.