The state of war: Armed conflicts in 2022

STATUS QUO

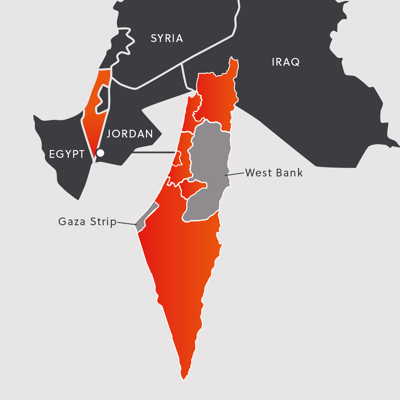

ISRAEL-PALESTINE

The Israeli-Palestinian peace process has remained frozen since 2014, with no major push from the international community to urge the two sides to negotiate. Senior Israeli leaders and their Palestinian counterparts continue to accuse one another of obstructing peace efforts. Amid major and longstanding disagreements, in May 2021, a land dispute in Sheikh Jarrah, East Jerusalem, prompted violent protests and riots in Israel and the West Bank, culminating in yet another war between Israel, and Hamas, which controls the Gaza Strip. The war killed more than 250 Palestinians and a dozen people in Israel. Israeli airstrikes caused significant destruction in the Gaza Strip, while Hamas’ indiscriminate rocket attacks damaged public and private property, particularly in southern Israel. Although neither side is eager to provoke a sustained conflict, the 2021 flare-up, the fourth major conflict between the two parties since 2008, is an important reminder of simmering tensions. 2022 is likely to see Hamas focus on reconstruction efforts in Gaza while a disparate coalition government in Israel could see a refocus on domestic affairs. Yet, given the conflict remains unresolved, occasional retaliatory actions between the two parties will remain an ever-present threat.

The Israeli-Palestinian peace process has remained frozen since 2014, with no major push from the international community to urge the two sides to negotiate. Senior Israeli leaders and their Palestinian counterparts continue to accuse one another of obstructing peace efforts. Amid major and longstanding disagreements, in May 2021, a land dispute in Sheikh Jarrah, East Jerusalem, prompted violent protests and riots in Israel and the West Bank, culminating in yet another war between Israel, and Hamas, which controls the Gaza Strip. The war killed more than 250 Palestinians and a dozen people in Israel. Israeli airstrikes caused significant destruction in the Gaza Strip, while Hamas’ indiscriminate rocket attacks damaged public and private property, particularly in southern Israel. Although neither side is eager to provoke a sustained conflict, the 2021 flare-up, the fourth major conflict between the two parties since 2008, is an important reminder of simmering tensions. 2022 is likely to see Hamas focus on reconstruction efforts in Gaza while a disparate coalition government in Israel could see a refocus on domestic affairs. Yet, given the conflict remains unresolved, occasional retaliatory actions between the two parties will remain an ever-present threat.

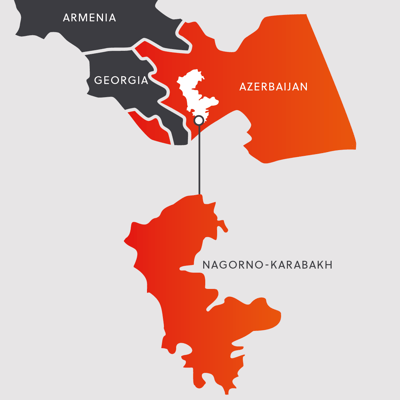

NAGORNO-KARABAKH

In the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh region, the longstanding conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, will continue to result in cross-border shelling and limited casualties in 2022. However, a major war like the 2020 conflict is not on the cards. The September-November 2020 war was the most significant flare-up since the 1990s, in which at least 6,000 troops from both sides were killed. A ceasefire brokered by Russia is largely holding, though occasional violations indicate that the underlying tensions remain. A militarily weaker Armenia will be hesitant to participate in another war in the short-term, but the conflict is far from resolved and 2022 is likely to see a continuation of ceasefire violations. The question will be whether sustained violations will be enough of a catalyst to spark renewed fighting within 2022.

In the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh region, the longstanding conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, will continue to result in cross-border shelling and limited casualties in 2022. However, a major war like the 2020 conflict is not on the cards. The September-November 2020 war was the most significant flare-up since the 1990s, in which at least 6,000 troops from both sides were killed. A ceasefire brokered by Russia is largely holding, though occasional violations indicate that the underlying tensions remain. A militarily weaker Armenia will be hesitant to participate in another war in the short-term, but the conflict is far from resolved and 2022 is likely to see a continuation of ceasefire violations. The question will be whether sustained violations will be enough of a catalyst to spark renewed fighting within 2022.

POTENTIAL ESCALATION

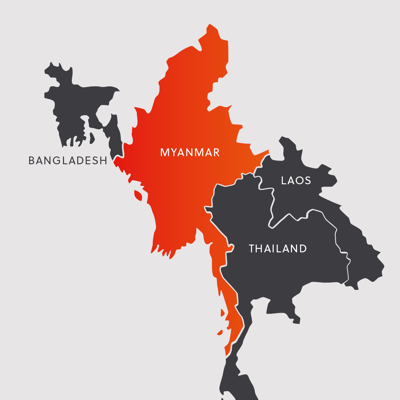

MYANMAR

The security situation in Myanmar is likely to worsen in 2022. Since the February 2021 military coup, there have been countrywide protests against the junta, which has responded with force, killing close to a thousand people in the last year. Protests and related industrial strikes, and the military’s heavy-handed response, have resulted in significant commercial disruptions. Furthermore, anti-junta elements operating under the People’s Defence Force (PDF) have carried out asymmetric attacks (such as low-impact bombings and shootings) against the military in several parts of the country, including Mandalay, Chin and Kachin states. These attacks have also targeted many telecommunication towers, and other government-linked infrastructure, with the aim to destabilise the military’s rule. In some cases, PDF units have collaborated with armed separatist groups that are engaged in a longstanding insurgency against the Myanmar army, including the Chin National Army and the Kachin Independence Army. These groups will continue to pose a formidable security challenge to the military in 2022. Although they remain incapable of removing the junta from power, Myanmar is likely to experience flare-ups of violence this year.

The security situation in Myanmar is likely to worsen in 2022. Since the February 2021 military coup, there have been countrywide protests against the junta, which has responded with force, killing close to a thousand people in the last year. Protests and related industrial strikes, and the military’s heavy-handed response, have resulted in significant commercial disruptions. Furthermore, anti-junta elements operating under the People’s Defence Force (PDF) have carried out asymmetric attacks (such as low-impact bombings and shootings) against the military in several parts of the country, including Mandalay, Chin and Kachin states. These attacks have also targeted many telecommunication towers, and other government-linked infrastructure, with the aim to destabilise the military’s rule. In some cases, PDF units have collaborated with armed separatist groups that are engaged in a longstanding insurgency against the Myanmar army, including the Chin National Army and the Kachin Independence Army. These groups will continue to pose a formidable security challenge to the military in 2022. Although they remain incapable of removing the junta from power, Myanmar is likely to experience flare-ups of violence this year.

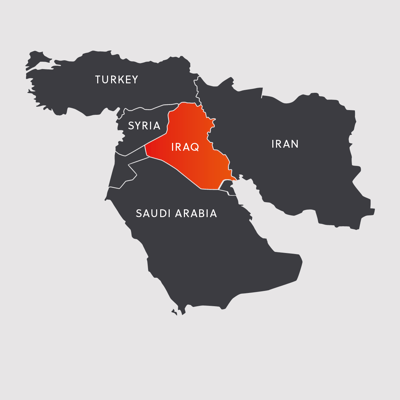

IRAQ

The security situation in Iraq will remain precarious and potentially worsen in 2022. The proxy war between Iran and the US, and others, will continue to play out in the country. Iran-backed militias likely retain the intent to target US diplomatic and military assets in rocket attacks, while the November 2021 assassination attempt targeting Prime Minister Mustafa Al Khadhimi highlights the threat to government personnel and interests. These militias have also encouraged violent protests in Baghdad, after political parties representing them performed poorly in October general elections. Tensions between Iraqi nationalist factions, who performed well in the general elections, and Iran-backed factions who claim the poll was fraudulent, are likely to persist into 2022. The longstanding tensions between the Iraqi central government and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) over issues such as revenue sharing and territorial control will further complicate Iraq’s security landscape. These bitter disputes have created a security vacuum in parts of Iraq, allowing the Islamic State (IS) insurgency – which primary manifests in hit-and-run attacks, roadside bombings, and kidnappings against security forces and civilians – to gain momentum over the past year. There are indications that IS – which is primarily active in governorates north of Baghdad – is bolstering its presence in southern Iraq, as demonstrated by the rare terror attack in Basra in December 2021. This will mean Iraq will face an array of conflicts in the coming months.

The security situation in Iraq will remain precarious and potentially worsen in 2022. The proxy war between Iran and the US, and others, will continue to play out in the country. Iran-backed militias likely retain the intent to target US diplomatic and military assets in rocket attacks, while the November 2021 assassination attempt targeting Prime Minister Mustafa Al Khadhimi highlights the threat to government personnel and interests. These militias have also encouraged violent protests in Baghdad, after political parties representing them performed poorly in October general elections. Tensions between Iraqi nationalist factions, who performed well in the general elections, and Iran-backed factions who claim the poll was fraudulent, are likely to persist into 2022. The longstanding tensions between the Iraqi central government and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) over issues such as revenue sharing and territorial control will further complicate Iraq’s security landscape. These bitter disputes have created a security vacuum in parts of Iraq, allowing the Islamic State (IS) insurgency – which primary manifests in hit-and-run attacks, roadside bombings, and kidnappings against security forces and civilians – to gain momentum over the past year. There are indications that IS – which is primarily active in governorates north of Baghdad – is bolstering its presence in southern Iraq, as demonstrated by the rare terror attack in Basra in December 2021. This will mean Iraq will face an array of conflicts in the coming months.

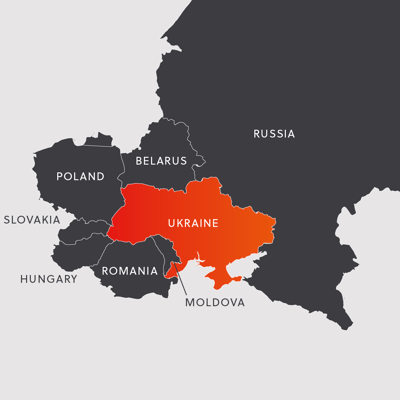

EASTERN UKRAINE

In eastern Ukraine’s Donbas region, government troops and pro-Russian separatists (backed by Russia, both materially and militarily) have been engaged in conflict since April 2014. The 2014 and 2015 Minsk agreements, which called for an immediate and comprehensive ceasefire, have effectively failed and the conflict is now in stalemate. Eastern Ukraine continues to be the stage for the renewed rivalry between western powers and Russia. Accordingly, a clear and immediate resolution to the conflict is unlikely given that the drivers of this war are, at least in part, determined by broader geopolitical posturing. Russia is set to continue to coerce Ukraine against increasing its western alignment. In fact, in late 2021, Russia deployed more than 100,000 troops and hundreds of tanks, self-propelled artillery and even short-range ballistic missiles near the Ukrainian border. Russia’s actions are largely rooted in its demand for legal guarantees that Ukraine will never join NATO or host its missile systems, which Ukraine is highly unlikely to accept. The threat of increased Russian military involvement in Donbas has heightened tensions in the region and renewed fears of an escalation in fighting over the coming months.

In eastern Ukraine’s Donbas region, government troops and pro-Russian separatists (backed by Russia, both materially and militarily) have been engaged in conflict since April 2014. The 2014 and 2015 Minsk agreements, which called for an immediate and comprehensive ceasefire, have effectively failed and the conflict is now in stalemate. Eastern Ukraine continues to be the stage for the renewed rivalry between western powers and Russia. Accordingly, a clear and immediate resolution to the conflict is unlikely given that the drivers of this war are, at least in part, determined by broader geopolitical posturing. Russia is set to continue to coerce Ukraine against increasing its western alignment. In fact, in late 2021, Russia deployed more than 100,000 troops and hundreds of tanks, self-propelled artillery and even short-range ballistic missiles near the Ukrainian border. Russia’s actions are largely rooted in its demand for legal guarantees that Ukraine will never join NATO or host its missile systems, which Ukraine is highly unlikely to accept. The threat of increased Russian military involvement in Donbas has heightened tensions in the region and renewed fears of an escalation in fighting over the coming months.

LIKELY DE-ESCALATION

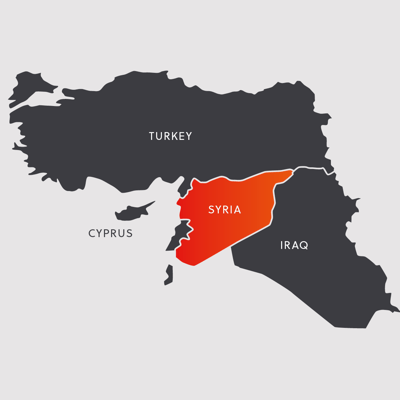

SYRIA

In Syria, the decade-old civil war appears to have reached a stalemate, with anti-regime rebels and Kurdish groups controlling most of northern Syria, and the Bashar Al Assad regime being in control of the rest of the country. Towards the end of 2021, Turkey had vowed to launch yet another offensive against Kurdish groups in north-eastern Syria, although a large offensive appears unlikely due to the presence of US and Russian troops in these areas. In north-western Syria, Syrian and Russian warplanes continue to carry out occasional airstrikes on rebel-held Idlib and surrounding areas, but a major offensive – which risks provoking a Turkish military response like 2019-20 – is not expected. These factors suggest that despite the volatile security landscape, Syria’s current fault lines, particularly its three territorial zones of control, will likely only become more entrenched in the coming year, with little resolution to the stalemate on offer.

In Syria, the decade-old civil war appears to have reached a stalemate, with anti-regime rebels and Kurdish groups controlling most of northern Syria, and the Bashar Al Assad regime being in control of the rest of the country. Towards the end of 2021, Turkey had vowed to launch yet another offensive against Kurdish groups in north-eastern Syria, although a large offensive appears unlikely due to the presence of US and Russian troops in these areas. In north-western Syria, Syrian and Russian warplanes continue to carry out occasional airstrikes on rebel-held Idlib and surrounding areas, but a major offensive – which risks provoking a Turkish military response like 2019-20 – is not expected. These factors suggest that despite the volatile security landscape, Syria’s current fault lines, particularly its three territorial zones of control, will likely only become more entrenched in the coming year, with little resolution to the stalemate on offer.

SIGNIFICANT UNCERTAINTY

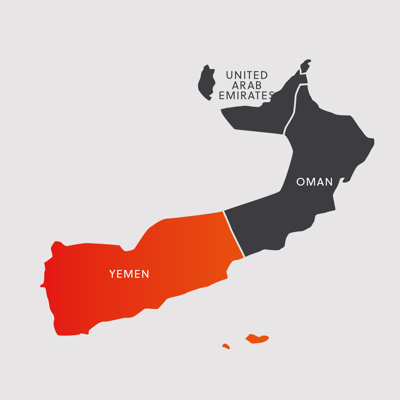

YEMEN

The political and security dynamics in Yemen remain deeply complex. The conflict between the Houthis and Yemeni government forces backed by the Saudi Arabia-led military coalition rages along several frontlines, including Ma’rib, Hodeidah and Taiz. And, in southern Yemen, there remains a mutual distrust between the government of President Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi and the UAE-backed separatist group, the Southern Transition Council (STC), despite a shaky alliance between them. While there is a potential for a war fought on two fronts, developments in the strategically significant Ma’rib Governorate will be the key determinant in Yemen’s future. Ma’rib Governorate is the last government stronghold in northern Yemen and the Houthis have been trying to capture it since February 2021. If Ma’rib should fall to the Houthis, the victors could advance towards Aden. Such a move will only prolong the conflict, due to fierce resistance expected from government forces, the STC and Saudi Arabia. Furthermore, the UAE could be drawn back to the battlefield to secure its own strategic interests in the south. Accordingly, all signs point to yet another complex year for Yemen’s protracted war.

The political and security dynamics in Yemen remain deeply complex. The conflict between the Houthis and Yemeni government forces backed by the Saudi Arabia-led military coalition rages along several frontlines, including Ma’rib, Hodeidah and Taiz. And, in southern Yemen, there remains a mutual distrust between the government of President Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi and the UAE-backed separatist group, the Southern Transition Council (STC), despite a shaky alliance between them. While there is a potential for a war fought on two fronts, developments in the strategically significant Ma’rib Governorate will be the key determinant in Yemen’s future. Ma’rib Governorate is the last government stronghold in northern Yemen and the Houthis have been trying to capture it since February 2021. If Ma’rib should fall to the Houthis, the victors could advance towards Aden. Such a move will only prolong the conflict, due to fierce resistance expected from government forces, the STC and Saudi Arabia. Furthermore, the UAE could be drawn back to the battlefield to secure its own strategic interests in the south. Accordingly, all signs point to yet another complex year for Yemen’s protracted war.

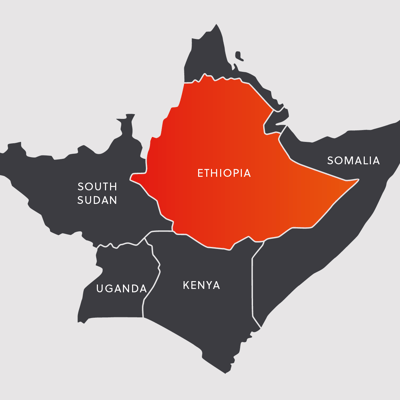

ETHIOPIA

Like Yemen, the conflict in Ethiopia could go in several directions in 2022. In November 2020, the Ethiopian army seized control of Mekelle, the capital of Tigray Region, in less than a month, removing the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) from power. However, Tigrayan forces regrouped in the following months, and by June 2021, they recaptured much of Tigray, including Mekelle. They have since formed alliances with several rebel groups, including the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA), captured territory in the neighbouring Amhara and Afar regions and vowed to seize Addis Ababa. Despite repeated international calls for a ceasefire, neither side has shown any interest in backing down. The TPLF’s capture of Dessie and Kombolcha, two strategic towns in Amhara Region, had raised concerns about the group marching to Addis Ababa, a concern only partially placated by the government’s recapture of the cities in early December. With an all-out victory unlikely for either side, Ethiopia risks being pulled into a protracted conflict in the coming year.

Like Yemen, the conflict in Ethiopia could go in several directions in 2022. In November 2020, the Ethiopian army seized control of Mekelle, the capital of Tigray Region, in less than a month, removing the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) from power. However, Tigrayan forces regrouped in the following months, and by June 2021, they recaptured much of Tigray, including Mekelle. They have since formed alliances with several rebel groups, including the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA), captured territory in the neighbouring Amhara and Afar regions and vowed to seize Addis Ababa. Despite repeated international calls for a ceasefire, neither side has shown any interest in backing down. The TPLF’s capture of Dessie and Kombolcha, two strategic towns in Amhara Region, had raised concerns about the group marching to Addis Ababa, a concern only partially placated by the government’s recapture of the cities in early December. With an all-out victory unlikely for either side, Ethiopia risks being pulled into a protracted conflict in the coming year.

LIBYA

Libya had seen a decline in war since June 2020, when Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA) retreated from Tripoli, having launched an offensive to capture the city in 2019. Yet, the 18-month peace processes designed to pave the way for December 2021 elections were marked by familiar challenges over the legitimacy of the newly formed government authorities. Ultimately, longstanding divisions along political, ideological, and tribal lines continue to hamper longer term peace efforts in the country, with rival political stakeholders and their militia backers eager to secure greater influence within Libya’s new political structure. 2022 is likely to be characterised by significant uncertainty as new leaders seek to bring their former adversaries alongside. Yet, with oil revenue allocations and administration set to be revised, the lucrative security contracts for oil facilities up for grabs and a failure to secure the withdraw of foreign mercenaries from the country in 2021, opportunities for new disputes backed by old tensions are ever present.

Libya had seen a decline in war since June 2020, when Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA) retreated from Tripoli, having launched an offensive to capture the city in 2019. Yet, the 18-month peace processes designed to pave the way for December 2021 elections were marked by familiar challenges over the legitimacy of the newly formed government authorities. Ultimately, longstanding divisions along political, ideological, and tribal lines continue to hamper longer term peace efforts in the country, with rival political stakeholders and their militia backers eager to secure greater influence within Libya’s new political structure. 2022 is likely to be characterised by significant uncertainty as new leaders seek to bring their former adversaries alongside. Yet, with oil revenue allocations and administration set to be revised, the lucrative security contracts for oil facilities up for grabs and a failure to secure the withdraw of foreign mercenaries from the country in 2021, opportunities for new disputes backed by old tensions are ever present.