Striking Gold: Militancy, Mining and Political Uncertainty in Mali

BUILDING AN INTENT TO STRIKE

Al Qaeda-aligned groups have previously demonstrated the capacity to target foreign-owned commercial interests in the Sahel. Al Mourabitoun was behind the January 2013 assault on the Tigantourine gas facility in In Amenas, Algeria, and the May 2013 attack against a French-owned Uranium mine in Arlit, Niger. More recently, in May 2016, AQIM again claimed to have attacked the French mine in Arlit in an assault orchestrated by the group’s southern outfit, Al Nasser. While the Nigerien government denied the attack had taken place and the French company declined to comment on the incident, it demonstrated a renewed intent to target higher profile commercial operations in the region, having come several weeks after a rocket attack on an oil facility in Krechba, Algeria, claimed by the group. This intent has now been cemented in the latest AQIM statement and we expect renewed attempts to target business entities going forward.

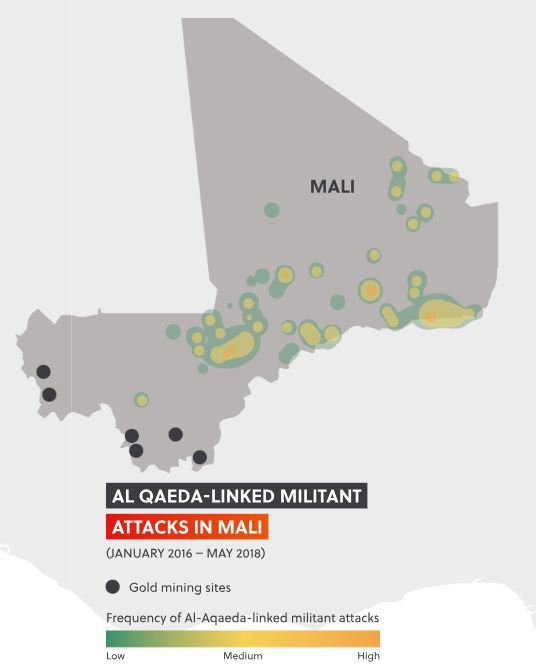

AQIM’s sub-Saharan Africa presence is most established in northern Mali, where Jamaat Nusrat Al Islam wal Muslimeen (JNIM), an Al Qaeda-linked coalition of Mali-based groups, has capitalised on absent government and entrenched smuggling networks in the Gao, Kidal and Timbuktu regions to bolster its insurgency. JNIM, and its various predecessors, have been linked to numerous attacks in the north. Since In Amenas, these have almost exclusively targeted UN, French and Malian security positions, leaving Mali’s mining regions in the southern and western parts of the country seemingly insulated from the threat. Past attacks have taken the form of improvised explosive device attacks, mortar and rocket attacks, kidnappings, suicide bombings and 168 attacks involving assaults, ambushes or assassinations. While these attacks serve JNIM, and others’, agenda in fighting against Malian and foreign military operations, an attack on a commercial mining facility would bring significant international attention to their campaign.

GETTING INTO POSITION

Since 2016, there has been a clear southward migration of the Islamist militant threat into central and southern Mali as well as into Burkina Faso – regions outside of these groups’ traditional areas of operation. Of the 250 Islamist militant attacks recorded in Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso in 2016, for example, approximately 20 percent of attacks occurred in Mali’s central and southern Mopti, Sikasso and Segou regions. Sikasso hosts at least four prominent gold mine complexes. The following year, this percentage increased. By the end of 2017, of the 276 attacks recorded in Mali and the West African region, more than 30 percent took place in central and southern Mali. More recently, between October 2017 and February 2018, JNIM claimed responsibility for an average of 12 attacks per month, having maintained a clear focus on Mali’s Mopti region since March 2017.

The inclusion of the Malian group Katiba Macina in the JNIM alliance has increased the group’s access to the southern regions of Segou and Mopti due to its ties with Fulani communities based there. As a result of high-level communal connections, JNIM has benefitted from local community support through intelligence gathering and the use of networks for logistical support. Recent links to the Fulani in particular, who do not maintain the same Arab lineage of the Tuareg tribes, has allowed militants to easily infiltrate central and southern Mali communities.

By the end of 2017, of the 276 attacks recorded in Mali and the West African region, more than 30 percent took place in central and southern Mali.

TESTING CAPABILITIES

These groups have not only increased their geographical spread within Mali and Burkina Faso, but their attacks have also become more brazen. The recent 2 March 2018 attack on the French embassy and military headquarters in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso demonstrated a higher level of tactical knowledge and growing capacity to target more high-profile assets. During the attack, which has since been claimed by JNIM, militants on foot attacked the French embassy while simultaneously detonating a suicide vehicle-borne improvised explosive device (SVBIED) at a military headquarters, reportedly targeting a meeting room used by members of the G5 Sahel, a regional block comprising Burkina Faso, Mali, Mauritania, Niger and Chad. Attacks on strategic infrastructure have also increased in recent months. For example, in March 2018, 30 suspected Islamist militants attacked the construction site of a dam located in Djenné, in the central Mopti Region. Although the militants evacuated the site employees, including South Korean nationals, they also set the construction site on fire. The dam project was expected to go online in July this year and the attack will result in the delay in irrigation supplies for 500km2 of land.

This increase in intent and capabilities, coupled with a clear southward migration on the part of Islamist militants, should not be ignored by mine operators in Mali’s Sikasso and Kayes regions. Furthermore, this increase, coupled with AQIM’s May warning, should be considered by all commercial operators in the wider Sahel region, from Mali to as far south as Côte d’Ivoire. Although lessons have been learnt since In Amenas and foreign companies are more aware of the requisite risk management needs of these operating environments, there remains cause for concern amid these changes in the operating environment. Monitoring the evolving threat environment is paramount to staying ahead of risks to business.

TROUBLE AHEAD

Mali is entering a period of political uncertainty ahead of a presidential election on 29 July. The political landscape in Mali is highly fractured and although the incumbent president, Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta (President Keïta), has confirmed he will seek a second term in office, his reputation has been severely damaged by the rise of Islamist militancy in the country under his rule. Meanwhile, insecurity in the north of Mali may prevent elections from taking place there; this is unlikely to appease Tuareg leaders eager to secure promises of increased autonomy and political representation guaranteed in the June 2015 peace deal. The deal aimed to end the Tuareg rebellion that broke out in 2012, but tensions among the warring parties remain high. A failure to hold elections in the north will delegitimise the election results and may encourage Tuareg groups, particularly those already wavering in their commitment to the July 2015 deal, to rearm against the government. Islamist militant groups have already demonstrated their ability to capitalise on insecurity in the north in 2012, when AQIM and its domestic affiliates piggy-backed off Tuareg campaigns to secure their own territorial gains in the 2013-2015 civil war. Now, political uncertainty, coupled with government plans to revise Mali’s mining codes, will make the coming months increasing difficult to navigate. Despite initial negotiations with mining firms over the proposed mining code amendments, a ruling administration pressured by the upcoming election, as well as increasingly aggressive Islamist militants, may look to implement unilateral reforms in the key sector as a sign of strength to the electorate.

While mining in Mali is becoming increasingly precarious on several fronts, Al Qaeda-affiliated groups will be ready and waiting to strike. Already, under a more aggressive Al Qaeda leadership, with leader Ayman Al Zawahiri calling for continued jihad in the Maghreb in the wake of the 2 March attack on the French Embassy, AQIM is positioning itself to carry out more sophisticated assaults on infrastructure and extractive facilities as Mali’s operating environment becomes more vulnerable. Furthermore, Mali’s precarious northern environment offers AQIM and its affiliates a safe haven from which to threaten the wider Sahel region, as already evident in the Islamist insurgency in northern Burkina Faso. These groups are capable of expanding their threats southward, and this will present a future problem for other West African states, who may not be on the same security footing as Mali.