Ripping off the Band-Aid: Understanding the Resurgence in Somali Piracy

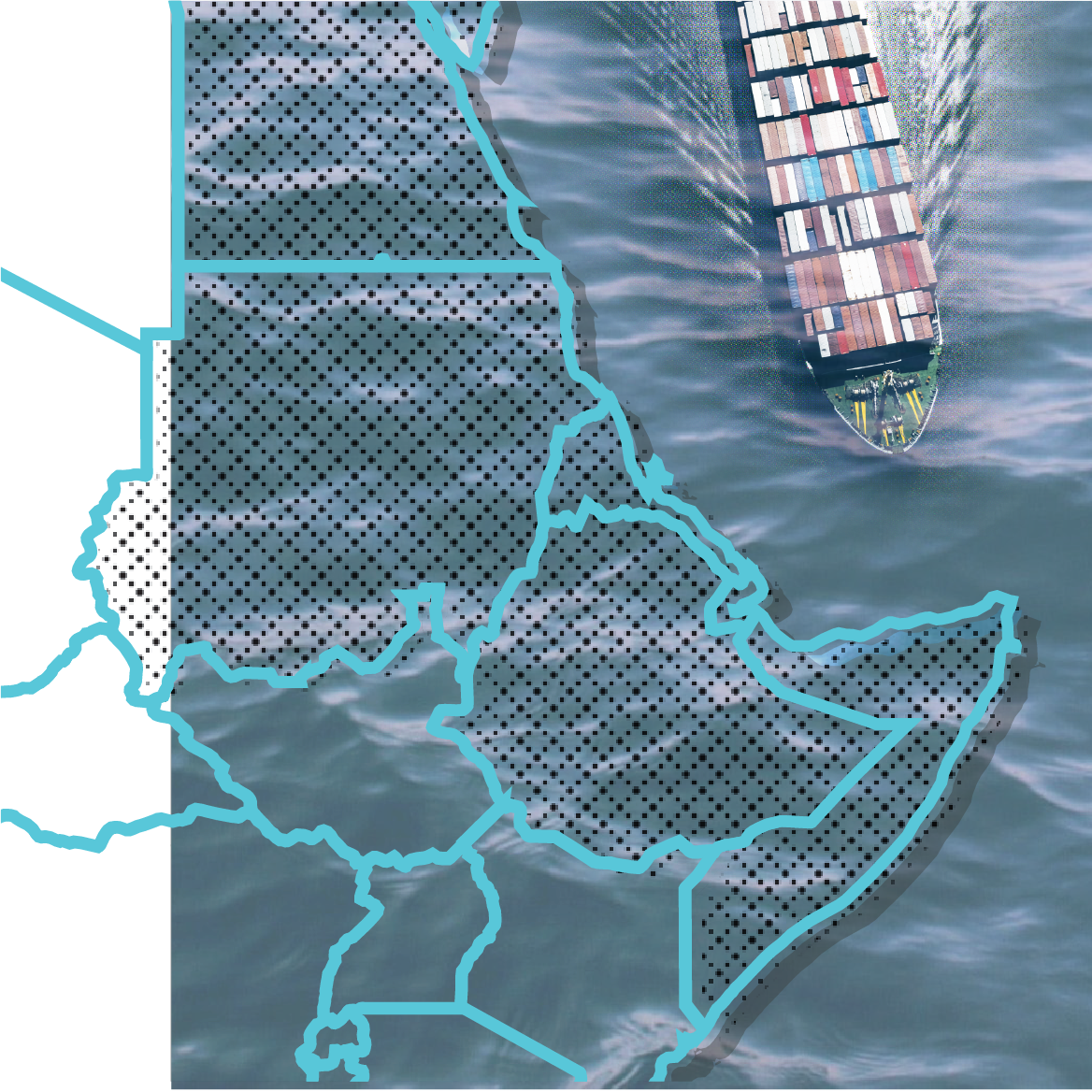

Somalia-based pirates attacked five commercial vessels off Somalia’s coast between March and May 2017, marking the first series of successful attacks in five years. At its height in 2011, Somalia-based piracy cost the global shipping industry close to USD 7 billion annually, according to the International Maritime Bureau. By 2016, internationally coordinated naval and private counterpiracy measures had effectively reduced this cost, comprising losses due to attacks as well as insurance premiums, armed guards and other protection measures, to USD 1.3 billion. While successful, these measures have created a false sense of security as commercial shipping firms, as well as naval forces, have recently scaled back security operations. This grave miscalculation, which ignores the onshore drivers of Somali piracy, has made ships vulnerable once more.

While statistics claim there were no successful pirate attacks off Somalia in 2016, they conceal the fact that the number of failed and suspicious incidents in the region actually increased, according to NGO Oceans Beyond Piracy. Armed security teams reportedly deterred at least 11 attacks against commercial vessels and small-scale attacks on local vessels continued unabated, indicating a persistent threat.

At its height in 2011, Somalia-based piracy cost the global shipping industry close to USD 7 billion annually.

Yet, costly international naval efforts have been reduced in recent months, as evidenced by the December 2016 end of the NATO-led ‘Operation Shield’. Private companies have also scaled back expensive private security measures, including armed guards and the employment of Best Management Practices (BMPs). These cutbacks have made ships more vulnerable to this persistent threat. When the Comoros-flagged MT ARIS 23 was attacked on 13 March 2017, the first successful attack in five years, the slow-moving tanker was preparing to cut through the Socotra Gap. This route is ill-advised by BMPs, but is a cost-cutting and time-saving alternative. Furthermore, there were no armed guards onboard.

Onshore drivers of maritime crime, including piracy, partially explain why this threat has persisted. Economic hardship has facilitated recruitment for pirate gangs, which operate with near impunity in the governance vacuum that exists across Somalia, including parts of Puntland. Since 2012, pirates have diversified their criminal activity to include contraband smuggling but have also turned to piracy when afforded the opportunity. Although there has been some success in fostering local capacity in addressing piracy, with local leaders reportedly facilitating the release of the MT ARIS 23 allegedly without ransom payment, this local pushback has yet to be engrained. Achieving this will become increasingly difficult however, particularly as onshore hardships are due to worsen as drought endures in the region. With the onshore causes of piracy unaddressed, it is therefore too early to peel back counterpiracy measures.