Kenya Waits

The Kenyan Supreme Court’s announcement that the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC), Kenya’s election body, had “failed, neglected or refused to conduct the presidential election in a manner consistent with the dictates of the constitution” was unexpected. While the country awaits the Court’s full ruling, and the subsequent election re-run, investors are wondering what impact the decision will have on Kenya’s political and economic stability.

RENEWED RISK OF POLITICAL INSTABILITY

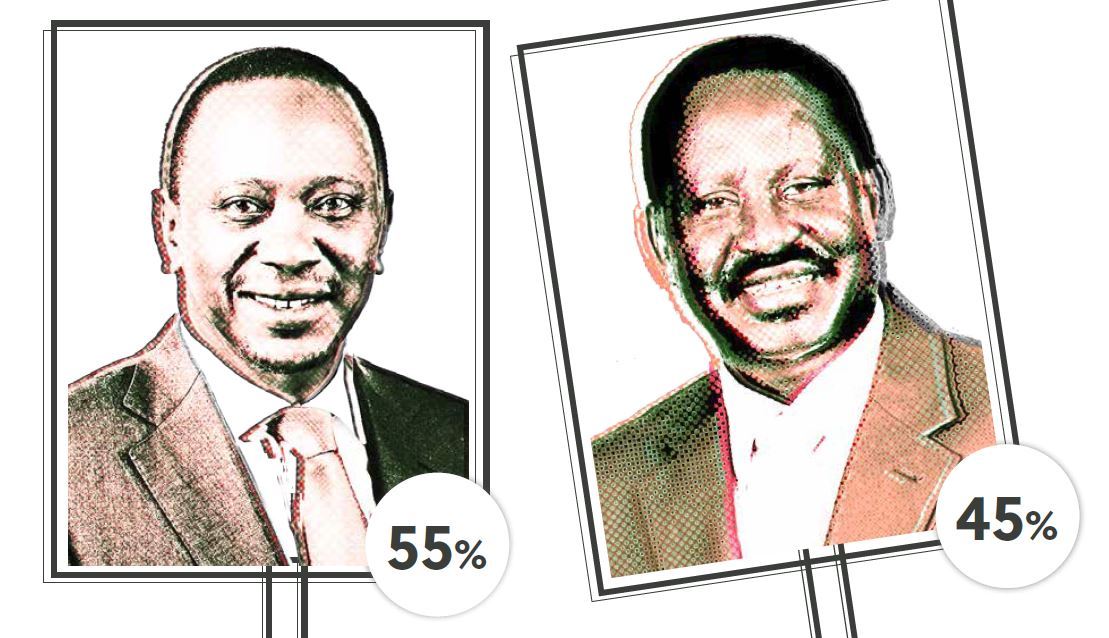

Whilst appearing to confirm concerns that the IEBC was biased in its conduct during the election, the Supreme Court’s judgement is a clear sign of the Kenyan judiciary asserting independence from the executive, setting a precedent for governance and the rule of law in the region. Despite previous criticism of the Court, opposition candidate Raila Odinga, who had lost August’s election with around 45% of the popular vote, praised the judgement. The incumbent, and victor with around 55% of the vote, President Uhuru Kenyatta, also initially accepted the ruling.

Both candidates, however, have subsequently voiced stronger rhetoric. Kenyatta stated that he “will revisit” and “fix” the Supreme Court if elected, and Odinga has challenged the scheduled date of 17 October for the re-run, alleging that it was set without consultation, and that he will not take part “without legal and constitutional guarantees”.

The re-run also raises practical difficulties: August’s polls were reportedly the world’s second most expensive, costing nearly USD 480 million, and the logistics of organising another election within two months will prove costly. Both presidential contenders also need to refill their election war chests. These practical concerns, and the contenders’ increasingly ill-tempered rhetoric, are fuelling fears of a resumption of the ethnic and political violence that has marred previous Kenyan elections.

Violence sparked directly by the election is not the only risk. During October’s campaign, both candidates remained largely tight-lipped on the insecurity generated by flashpoint issues of land tenure and property rights, which have been exacerbated by a drought in the north impacting cattle herders. AlShabaab, in neighbouring Somalia, also still poses a persistent threat, and counter-terrorism marks one of the few clear policy differences between the presidential contenders: Kenyatta has said that Kenyan troops will remain as part of the African Union AMISOM force until Somalia is stable, while Odinga has called for a phased troop withdrawal.

August’s polls were reportedly the world’s second most expensive, costing nearly USD 480 million

A ROBUST TECHNOLOGY-DRIVEN ECONOMY UNABLE TO SHAKE OFF CORRUPTION

Fears of instability, and the unexpectedly prolonged political uncertainty, are expected to slow Kenya’s economic growth in the short term. Shares on Nairobi’s Securities Exchange dropped 2% following the Court’s ruling. Nevertheless, Kenya’s economy remains well positioned, not having suffered the same weak growth as the region’s largest energy exporters. GDP growth was nearly 6% in 2016, in comparison with the sub-Saharan Africa average of 1.3%, and is forecast by the IMF to remain strong, averaging 5.9% annually between 2017 and 2021. Challenges remain in reducing Kenya’s fiscal deficit, estimated to be 8.3% in the fiscal year to June 2017, and in mitigating the effects of drought in northern Kenya; however, the government reports to have secured lending to meet its borrowing plans of around USD 1.5 billion for 2016-17, and a potential Eurobond issuance in late 2017 indicates that investors remain confident of Kenya’s prospects.

Part of this economic confidence can be attributed to Kenya’s enthusiastic embrace of technology, leading to its label as Africa’s ‘Silicon Savannah’, and its production of such innovations as M-Pesa, now the world’s largest mobile payment system, and M-Akiba, soon to be the world’s first sovereign bond sold exclusively through mobile platforms. This phenomenon was reflected in the election: the August poll was Kenya’s most technology-driven yet, from the use of biometric voter registration to eliminate ‘ghost’ voters, to the transmission of results from polling stations via mobile phones. Technology even played a part in the Supreme Court’s ruling, when Chief Justice David Maraga pointed to the IEBC’s failure to use both an electronic transmission system to relay vote records, and a public portal for tallying the results.

Fears of instability, and the unexpectedly prolonged political uncertainty, are expected to slow Kenya’s economic growth.

Yet there was a darker side to this high-tech democratic exercise, with the murder of the IEBC’s head of technology prior to the vote. Kenya’s economic vibrancy is likewise marred by its Achilles heel: endemic corruption. The Supreme Court judgement sends a powerful message to Kenya’s governing class that the judiciary is prepared to stand up to the executive, but Kenya has a long way to go in tackling graft. Tentative progress has been made in recent years: in 2016, Kenya signed up to the East African Community Code of Conduct for Ethical Business Practices, and its Parliament passed the Kenya Bribery Bill, which criminalised facilitation payments, and established rules for gifts that public officials can accept. Yet enforcement is weak and trials rarely result in prosecutions. Although the government has brought corruption charges against several high-ranking individuals since 2015, President Kenyatta’s inner circle remains untouched. In the latest scandal, in May, the US Embassy in Kenya suspended USD21 million in aid through Kenya’s Ministry of Health, citing concerns of corruption and weak accounting procedures. The next weeks and months will be crucial for Kenya. How the country responds to the Supreme Court decision, both politically and economically, will determine whether Kenya can conquer its challenges of insecurity and corruption.