From militants to ministers: The changing threats of kidnapping and extortion in Afghanistan

The Taliban’s takeover in Afghanistan in mid-August has raised concerns about how the threats of kidnapping, wrongful detention and extortion will evolve in an already uncertain security environment. Although the Taliban’s victory has ended the civil war, the lack of professionalism and respect for human rights within the Taliban itself, and a resurgence of the Islamic State militant group, mean the security situation for both locals and foreign nationals in country remains volatile. The Taliban may have de jure control of Afghanistan, but in reality their control is far from centralised and far from complete – the country remains a high-risk operating environment. Even if the political will to enact meaningful security improvements emerges, an already unlikely prospect for the time being, a faltering economy and endemic corruption are likely to undermine the new government’s ability to do so.

Here we provide a guide to the evolving threats of kidnap, wrongful detention and extortion in Afghanistan under Taliban rule.

THE TALIBAN

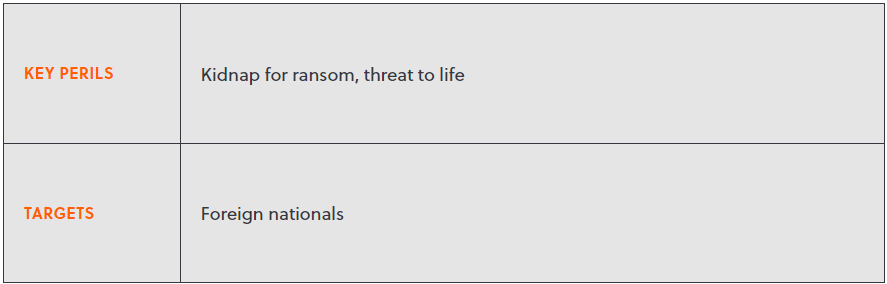

The new government is unlikely to pursue traditional kidnap for ransom activities, at least not in a centrally sanctioned manner.

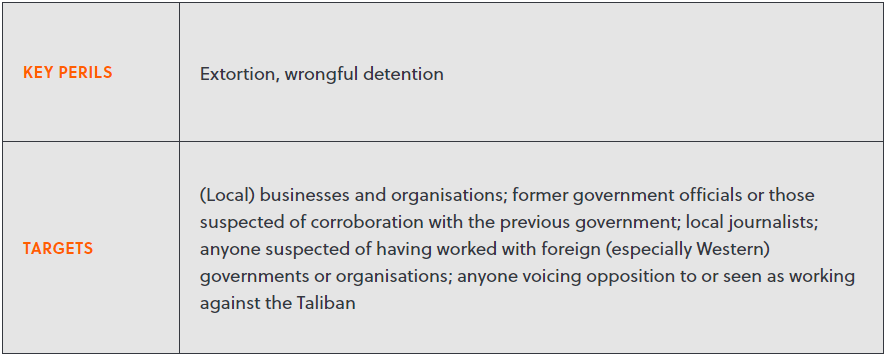

However, it remains to be seen how much control the central government in Kabul will have at the provincial or sub-provincial levels. On the one hand, consolidating power will mean appeasing a more modernised and liberalised society than the one they presided over 20 years ago. On the other it will, at least in the short term, entail a business-as-usual approach to the extensive ‘taxation’ and extortion schemes the group has run in the past. As a result, wrongful detention or threats to life may become less prominent perils, particularly for foreign operators and attacks against dissidents or opponents of the regime are likely to be increasingly covert. Yet, with the need for extortion fees and taxes to prop up the Taliban’s finances, at least until the economy can stabilise, local and foreign businesses will remain under threat of extortion for the foreseeable future.

THE ISLAMIC STATE

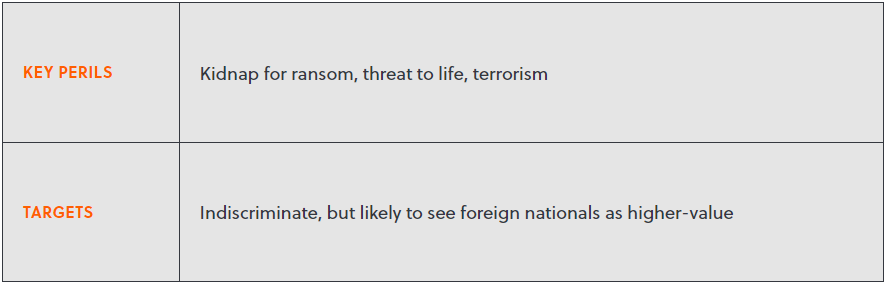

The Taliban has a fractured relationship with other Islamic militant groups. With an established presence of an estimated 2,000+ fighters in the country, Islamic State-Khorasan (IS-K) is a prominent threat actor, mainly targeting Taliban fighters and security forces.

Although there is little information available regarding the group’s kidnapping activities, they likely retain a high intent to target foreign nationals in kidnappings for ransom or political gain. IS-K will likely stage opportunistic attacks – for instance targeting foreign journalists, aid workers or others transiting through their area of operations.

There is also an indirect threat stemming from IS-K’s intent to target both the Taliban and foreign nationals. As evidenced by the attack on Kabul airport in August 2021, the group can carry out high-casualty attacks, including in Kabul. High profile events such as official conferences, high-level meetings or public ceremonies, present an attractive target for IS-K.

AL QAEDA

The Taliban retain close ties with Al Qaeda, which has an estimated 200-500 fighters in Afghanistan across 15 of its 34 provinces.

Many of the recently announced cabinet have worked with Al Qaeda in the past, and it seems unlikely that the Taliban would (or even could) cut ties with the group. At the very least, because of the two groups’ intertwined histories, it would likely be an internally divisive decision, and at worst, Al Qaeda could respond to the rebuff by turning its extensive military expertise and organisational capabilities against the Taliban. Retaining close ties with Al Qaeda may also help the Taliban in combating other groups such as IS-K. And, in truth many low-level combatants serve both groups, so the separation is somewhat arbitrary.

However, particularly on the international front the Taliban will want to distance themselves from Al Qaeda (or even publicly denounce them), which unlike the Taliban, is seen as a major terrorist threat internationally. Their affiliation with the sitting government is likely to somewhat temper Al Qaeda’s willingness to stage attacks in Afghanistan. Yet, this relationship is likely to prove increasing precarious for both parties. In the past Al Qaeda has specifically called for the kidnappings of foreigners in Afghanistan, and with this intent likely to persist, there is no guarantee that the Taliban can or will prevent such attacks on Afghanistan soil.