By hook or by crook: The crime / terror nexus

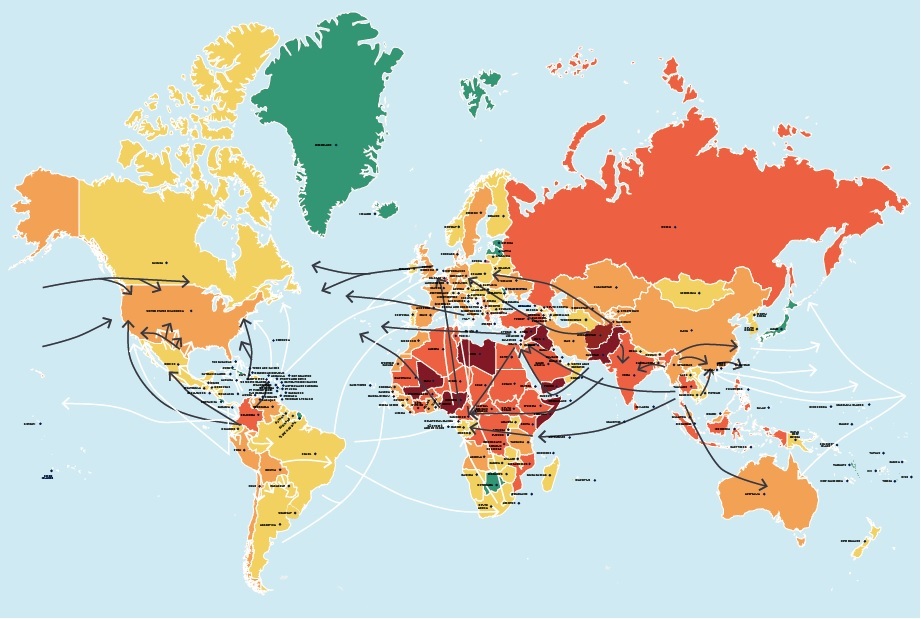

Terrorist groups have long leveraged ties to organised criminal groups to support their respective campaigns. These ties have ranged from direct or indirect involvement in illegal activities to fund terrorist activities, through to providing access to weapons and other materials required to orchestrate attacks. Across the globe, terrorist organisations including Al Qaeda affiliates, Colombia’s Ejército de Liberación Nacional (ELN) and even the Arakan Army in Myanmar, have relied on illegal activities to sustain their campaigns. One group has been able to capitalise on the symbiotic relationship between terrorism and crime at unprecedented levels. Prior to the fall of the Caliphate in Iraq and Syria, Islamic State (IS) is reported to have generated over USD 6 billion in revenues in 2015, the majority of which involved illicit activities. Yet, even with the fall of the IS Caliphate in 2017, the systemic ties between terrorist groups, crime organisations and their individual members persist. In fact, in 2019 the UN Security Council claimed that the ties between transnational organised crime and terrorist groups are increasing. In response, in July this year, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 2482, calling on member states to increase their efforts to dismantle links between international terrorism and organised crime.

A key challenge in addressing these ties is their diverse nature. The interactions between terrorist groups and crime organisations vary considerably, from individuals alternating between the role of militant and criminal on the ground, to terrorist groups using illicit channels to gain access to money and illegal provisions such as weapons. Certain groups have also adopted their own criminal practices to directly fund operations, side-lining established criminal organisations.

In 2019 the UN Security Council claimed that the ties between transnational organised crime and terrorist groups are increasing.

A means to an end

One of the most common forms of interaction between terrorists and their criminal counterparts is purely operational. Criminal organisations offer access to firearms and other weapons, as well as access to counterfeit documentation and smuggling routes to move personnel. By their very nature, terrorist organisations are inherently dependent on the criminal underworld to do their covert bidding. Such interaction between terrorist and criminal groups is largely opportunistic and fleeting, fluctuating in response to demand and supply.

Yet, while crime organisations supply a means to an end, several terrorist organisations have cut out the middle man, instead gaining direct access to lucrative illegal markets. The Taliban in Afghanistan remains a prominent example here. The Taliban’s production and trafficking of heroin generated at least USD 3 billion in revenue in 2016. In the last three years, poppy production in Afghanistan has soared as the Taliban have expanded their control over the drug market. Illicit poppy production now covers at least 328,000 hectares of land, in comparison to 74,000 hectares when US and British forces invaded Afghanistan in 2001. The Taliban have extorted poppy farmers to fund their insurgency for years. However, in 2019 top Afghan officials stated that the Taliban are increasing direct involvement in production of heroin and morphine, establishing and managing laboratories in areas under their control.

A family affair

Individual members of terrorist groups and criminal organisations further cement the crime / terror nexus on the ground. In remote areas such as the Sahel, individuals maintain transient roles of both ‘militant’ and ‘trafficker’, while simultaneously relying on close, trusted familial and tribal ties to carry out their respective activities. The infamous Al Qaeda commander, and later the head of the now defunct Al Mourabitoun, Mokhtar Belmokhtar, was a well-known drug trafficker. Meanwhile, Al Qaeda’s regional player, Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) has provided protection to cocaine convoys and charged drug traffickers transit fees for areas under its control in the Sahel. While Al Qaeda’s regional leadership has changed hands and new players like Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) and IS in the Greater Sahel (ISGS) have come to the fore in recent years, relationships between these terrorist groups and their trafficking counterparts have persisted.

Redemption

At its height in 2015, IS represented the ultimate success story of the crime / terror nexus. While the group was able to leverage criminal activity in areas under its control through bank looting, extortion, and the control of oil and gas reservoirs, it also sought to diversify its funding through organised crime channels outside of its territory. This involved human trafficking, illegal oil trade and the smuggling of antiquities. Despite its territorial losses, the group is believed to have maintained at least some of its financial holdings. Its ties to criminal activity form a large part of this, including the extortion along oil-supply lines in areas where IS affiliates operate, and the continued trafficking in antiquities. This monetary backing, coupled with lower operational costs in the wake of the failed caliphate, means that IS remains in a financial position to survive as a clandestine transnational terrorist group unless its organised crime lifelines are severed.

Outlook

With the crime / terror nexus here to stay, international players engaged in counter-terrorism initiatives will need to do more to cut these financial lifelines. While the passing of Resolution 2482 is a step in the right direction, it brings with it new complexities in determining the jurisdiction of who will be responsible for combating such illegal activity. In the interim, global terrorist organisations remain in a position to continue to leverage relationships with their criminal counterparts.