Ultimate price: The cost of environmental activism

They even succeeded in watering down the blah, blah, blah,” says Greta Thunberg, the Swedish environmental activists, about the new global climate pact agreed at the recent UN Climate Change Conference in Glasgow. Her disappointment echoes that of thousands of environmental activists around the world, frustrated with governments’ and corporations’ lack of urgency or ambition to tackle the climate crisis. These activists held near daily protests in Europe and elsewhere, as world leaders negotiated in Glasgow. In fact, the relaxation of Covid-19 restrictions has seen the return of environmental protests this year, after a lull in such activities for most of 2020. Fridays for Future, Extinction Rebellion, and other movements and groups are starting to stage protests and civil disobedience activities are at a level that has not been seen since 2019.

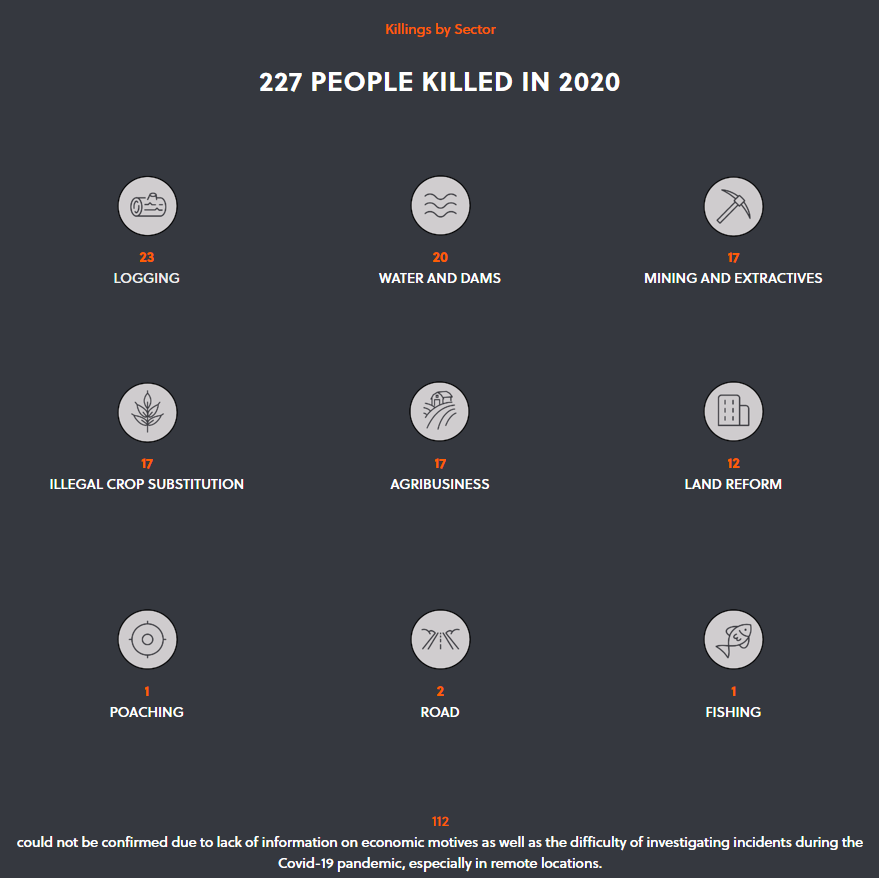

For most of these activists, who are largely operating in developed countries, partaking in protests and other disruptive acts carry limited risks. At the very worst, they are arrested and prosecuted for illegal activities. In other parts of the world, however, especially in developing countries with a weak rule of law, activists face much harsher consequences for trying to protect the environment, which is often directly linked to their livelihoods. In 2020 alone, 227 environmental defenders were killed worldwide, an average of more than four people a week. Many activists also experience physical attacks (including sexual violence), death threats, criminalisation and arrests, smear campaigns, censorship, and other attempts to silence them, which are harder to quantify.

DEADLIEST YEAR, EVERY YEAR

Over the past five years, the number of people killed has increased steadily, with each new year being the deadliest in history, barring a drop in 2018. The killing of 227 people in 2020, the highest on record, contrasts with a decline in most crimes around the world last year due to various Covid-19 restrictions. In some countries, such as Colombia, restrictions made it easier for perpetrators to kill activists in their homes. More than a third of those killed around the world were indigenous peoples, defending their lands, livelihoods, and local environments against legal and illegal business ventures and criminal groups. Global Witness, an international NGO, estimates that the actual number of environmentalists killed every year is higher, due to several reasons including underreporting, government restrictions on independent media, and the difficulty of collecting data in conflict zones.

MOST DANGEROUS COUNTRIES FOR ENVIRONMENTALISTS

Of the 227 murders that occurred last year, 165 took place in Latin America, which has long been the most dangerous region for environmental defenders, where many criminal gangs and paramilitarily groups operate with a high level of impunity. Colombia, for the second year in a row, is the world’s deadliest country for environmentalists (65 murders), followed by Mexico (30), the Philippines (29), Brazil (20), and Honduras (17). While the local context is different in every country, a common thread running through these jurisdictions is the authorities’ inability or lack of political will to hold perpetrators to account. In some cases, governments have not only turned a blind eye to the activists’ plight but also enacted policies that are detrimental to them. For example, in June 2020, the Philippines government adopted a controversial anti-terrorism law that is reportedly being used by the authorities to label environmental and other activists as terrorists or communist rebels. In Brazil, President Jair Bolsonaro has consistently weakened environmental protections while championing deforestation of the Amazon, undermining indigenous rights in many cases. This, according to his critics, has encouraged attacks on environmental defenders and indigenous activists. There are also many cases of governments directly engaging in violence against activists.

COUNTING THE COSTS

Attacks on environmental defenders is not only a tragedy for the victims and their families – it can also be bad for business, in terms of both reputational and financial damages. In an academic study published in December 2020, researchers analysed 354 assassinations connected to mining and extractive minerals projects around the world in a 20-year period. They found that the killing of activists can have a notable impact on the share price and the bottom line of a mining company.

If a company’s name is mentioned in international media in relation to a murder, within ten days, the study showed, it experiences a median loss of more than USD 100 million in market capitalisation. This shows the significance of publicising abuses committed against environmental defenders, even if local authorities fail to administer justice. It also demonstrates that if companies are more proactive about trying to prevent these killings and other abuses against environmentalists, they can protect themselves from certain risks, notwithstanding the ethical considerations.

THE STUDY FOUND THAT IF A COMPANY’S NAME IS MENTIONED IN INTERNATIONAL MEDIA IN RELATION TO A MURDER, WITHIN TEN DAYS, IT CAN EXPERIENCE A MEDIAN LOSS OF MORE THAN USD 100 MILLION IN MARKET CAPITALISATION.

Nevertheless, there are many companies that are not well-known, and are not publicly listed or reliant on PR-savvy international investors. There are also murders that are simply not reported, let alone being connected to a company. The media and the market are not able to hold the perpetrators accountable.

AARHUS CONVENTION: ONE STEP IN THE RIGHT DIRECTION

Despite the lack of justice and accountability, some governments are starting to pay attention to the crisis. In October 2021, the EU and 46 countries that ratified the UN’s 1998 Aarhus Convention adopted a legally binding agreement to protect environmental activists. The new agreement establishes a post for a special rapporteur on environmental defenders, likely based at the UN, who will be able to provide a rapid response to alleged violations as stipulated under the Aarhus Convention. The special rapporteur will have many tools at their disposal to help activists in danger, such as issuing immediate and ongoing protection measures, releasing public statements, and bringing urgent cases to relevant human rights bodies for action.

The obvious limitation of this landmark agreement is that none of the countries where environmental activists were killed in 2020 are signatories to the Aarhus Convention, which was only ratified by European and Central Asian countries. Many developing countries – who are reliant on natural resource exploitation and large infrastructural projects to fill state coffers and drive economic growth – are unlikely to sign any legally binding agreement to protect environmentalists. Until this changes, “watering down the blah, blah, blah” will not be the only concern for environmental defenders. In some cases, they may end up paying the ultimate price.