The state of political violence: A sad state of affairs

THE COMEBACK COUPS

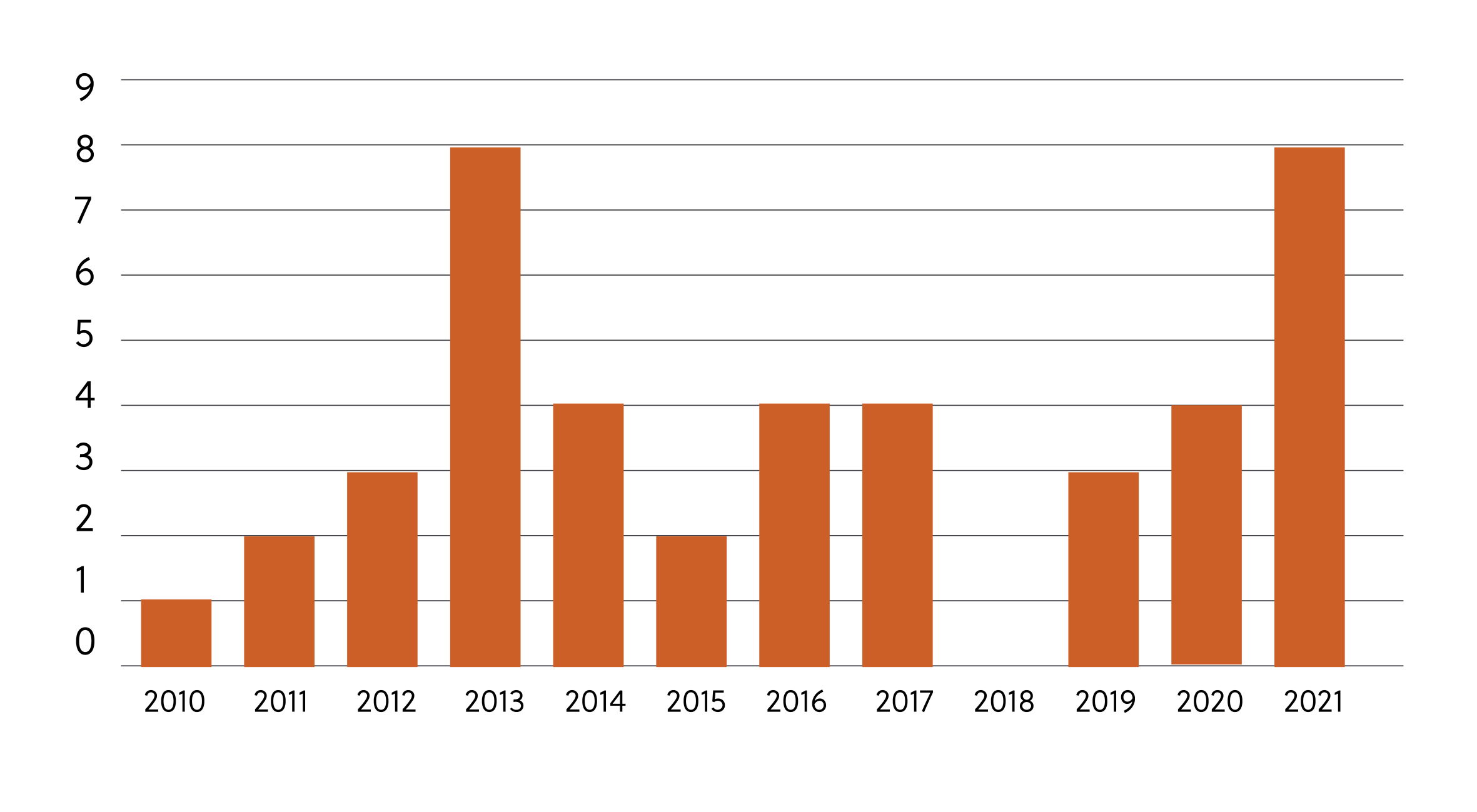

Coups d’état have made a comeback over the past few years, with 2021 being a standout year of five successful coups alone. Since the start of 2020, coups and coup attempts have been reported in the Central African Republic, Chad, Guinea, Mali, Myanmar, Sudan and elsewhere. The return of the military ousting of government, particularly in Africa, has prompted the African Union to identify “unconstitutional changes of government” as one of Africa’s most pressing security threats, with the February 2021 Myanmar coup a stark reminder that this threat is also present elsewhere.

NO GOOD DEED GOES UNPUNISHED

Of course, every country is different and the drivers of a military overthrow of a regime are manifold. However, there are a few common threads that run through the most recent coups, and coups historically. Across Chad, Guinea and Sudan the respective administrations of Idriss Déby, Alpha Condé and Omar Al Bashir were characterised by the erosion of democratic principles and practices where the ballot box no longer presented citizens with a legitimate opportunity for change. In his final election victory in 2015, for example, Al Bashir of Sudan secured 94 percent of the vote; Déby won 79 percent in Chad's April 2021 election, and Condé secured 60 percent and a third term in office in Guinea’s October 2020 vote – easy wins when factoring in that opposition parties were either barred from participating or their supporters were driven away from voting stations. This monopolisation of the political space had been enforced not only through fraudulent elections, but also the unpopular and at times unlawful extension of presidential term limits.

Specifically, since the turn of the century, long serving leaders in 20 African countries have attempted to relax or remove presidential term limits, much to the frustration of their citizens. And, recognising the failings of the democratic system that corrupt leaders used to cling to power, citizens have turned to the streets to voice their disgruntlement. Mass demonstrations calling for regime change preceded coups in Sudan and Guinea, with the military – themselves keen to secure a piece of the power pie – at the ready to intervene on the citizens’ behalf. Meanwhile, military stakeholders in Myanmar and Mali took it upon themselves to overthrow the government, taking advantage of weak institutions to roll back recent democratic gains.

Perhaps proving that there is no such phenomenon as a ‘good coup’, the political transitions in these countries have not paved the way for democratic reform as many citizens had hoped, instead offering little in the way of transition. And, despite claims to the contrary by transitional governments that a return civilian rule in pending, as the weeks and months have passed, it has become increasingly clear that the promise of democracy in these countries has proved false.

OF PROMISES AND PLANS

That said, interim leaders have been eager to secure and maintain some kind of legitimacy for their newfound authority, with coup leaders in Sudan, Mali and Guinea looking to bring international stakeholders and citizens alongside amid promises of an (eventual) return to civilian, and more importantly, democratic government. Recent coup leaders have agreed to extended transition periods under the genuine commitment or guise of ensuring a peaceful and fair transfer of power. In Chad, the Transitional Military Council which assumed power following the death of Déby in a skirmish with rebel forces in April, committed to an 18-month transition period, while in Mali, the latest coup leaders in June said they would respect their predecessors’ deadline to hold elections by February 2022, although this has since been delayed. Sudan is still technically in the middle of its 39-month transition despite suffering yet another coup in November 2021. Yet, while these promises have been penned in detailed implementation plans and timetables, they bring with them little in the way of certainty. As the second coup in Mali in under a year and the second coup in Sudan in under three years show, these countries remain highly vulnerable to further political instability.

OF THE PEOPLE, BY THE PEOPLE, FOR THE PEOPLE

With transitional governments, and their military backers, failing to usher in reform, people have once more gathered in the streets, this time to denounce the absence of democratic commitments from their newest leaders. Post-coup demonstrations have been seen in Sudan and Myanmar, where – despite exercising their right to secure a just civilian government – civilians have been met with a strong(er) arm of the law, with military stakeholders no longer working alongside the people but against them. Clampdowns on protesters and the opposition as well as activist arrests have become commonplace.

In Myanmar, persistent popular demonstrations and an ongoing civil disobedience campaign point to continued threats to the Tatmadaw junta, with the UN claiming the country is on the road to civil war. Over a year since the country’s general elections were rejected by the Tatmadaw – an important catalyst to the February coup – anti-coup activists are now turning to sabotage to undermine the military regime with over 400 telecommunication towers destroyed in the country in late 2021, for example. Meanwhile, in Sudan, thousands of protesters continue to reject the latest coup and the November reinstatement of Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok, indicating waning support for the 39-month transitional arrangement in place until December 2022 and a likely turbulent year for the country. Mali and Guinea may fare better on the political front if headway is made in securing civilian rule once more, but with military stakeholders in both countries likely to exercise substantial power in 2022, little can be guaranteed in the way of stability or reform.

COMPROMISED ELECTIONS, COMPROMISED DEMOCRACY

While coups present an outright threat to democracy, disputed elections pose a different type of challenge. Of course, some disputes are more objectively justified than others. Setting aside the cases where elections are a veneer for authoritarianism – think the widely condemned presidential elections in Belarus in October 2020 won by Aleksandr Lukashenko with 80 percent of the vote – other types of disputes pose a serious threat to the trust in democracy. Most visibly, disputed elections can result in violence, political uncertainty and a long recovery to stability. For this reason, Kenya’s 2022 general and presidential elections will be closely watched. But equally insidiously election disputes can gradually damage trust in the legitimacy of democratic processes and institutions, including the independence and strength of the judiciary. The US 2020 presidential elections show that even where the rule of law is upheld, vocal or widespread questioning of the fairness of elections can cause lasting trembles. Widening partisan rifts will be on display in the November 2022 US midterm elections. The US 2020 polls have also had an impact in Brazil, where Jair Bolsonaro is taking a leaf out of Donald Trump’s playbook ahead of the October 2022 election, by already questioning the legitimacy of the vote count.

DEMOCRACY PUT TO THE TEST

2022 will prove an interesting year on the political front for many jurisdictions and may prove an important test for the health of democracy across the world. There are many deadlines this year which will be crucial in moving the needle on for the global state of democracy, and determining whether we will see increased democratisation or further backslide. Be it gauging militaries’ appetite for handing power back to the people, cunning candidates swinging key polls, or simply the people taking matters into their own hands, 2022 will certainly see a return of political violence as a key risk on the global stage once more.

- DEMOCRACY LITMUS TESTS 2022 -

AUGUST: KENYA

Kenyans will head to the polls to elect a new president in August 2022 as Uhuru Kenyatta faces the end of his second and final term. Kenya has seen significant election related unrest in the past. In 2007, more than 1,000 people died in election related violence following disputed polls; and in 2017 after the presidential contest between Kenyatta and his then competitor, now turned ally, Raila Odinga, uncertainty lasted until the two buried the hatchet months after the polls. Since then, the two have grown close, cementing their pact through a proposed constitutional amendment which has been rejected in the courts and elsewhere criticised for being a guise to entrench their power. Kenyatta and Odinga’s key opponent is Kenyatta’s deputy president William Ruto, seeking to cast himself anti-establishment advocate of the poor and working class, although his credentials on these fronts is questionable. Regardless of the outcome, the stage is set for hotly contested elections and justifiably heightened fears over the fallout.

OCTOBER: BRAZIL

Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro will be heading into an election year without much reason for optimism. By all indications he faces an uphill struggle in his campaign. The pandemic-sceptic faces multiple challenges, including a Senate-led investigation in October 2021 which suggested the president should face charges for “crimes against humanity” over his handling of the pandemic (among other things). Bolsonaro’s approval ratings have plummeted. Preparing for a loss or a close race, Bolsonaro is already raising questions about the integrity of voting systems and infrastructure. Entering 2022, opinion polls show Bolsonaro trailing international favourite and former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. But Lula’s own credentials are tarnished, not least by a criminal conviction (though later overturned) on corruption charges in 2017. So, the race may yet be a close one. In the meantime, as the polls draw near, pro- and anti-government protests are likely to be a prominent feature of the 2022 landscape.

NOVEMBER: USA

Joe Biden will see a major test to his presidency in the November 2022 midterm elections for both houses of Congress; 34 of 100 seats in the Senate and all 435 House of Representatives seats are up for grabs. There is a lot going against Biden and his Democratic Party. To start, his approval ratings have dipped over issues such as runaway inflation and the hasty retreat from Afghanistan. Moreover, Democrats’ control over the Senate is razor thin and fragile. Beyond this, Republican control of state legislatures has allowed the party oversized influence over electoral redistricting, which in some states are set to strongly favour that party. While some of these new districts are likely to end up in the courts, they may not be resolved in time for the midterms. Now, while some Republicans cried foul over the 2020 elections, Democrats are increasingly frustrated over legal obstacles to what they view as fair representation. There is no doubt that the US is in for a prolonged period of deep polarisation.