The high cost of learning: Violent extortion plagues schools in Peru's La Libertad Department

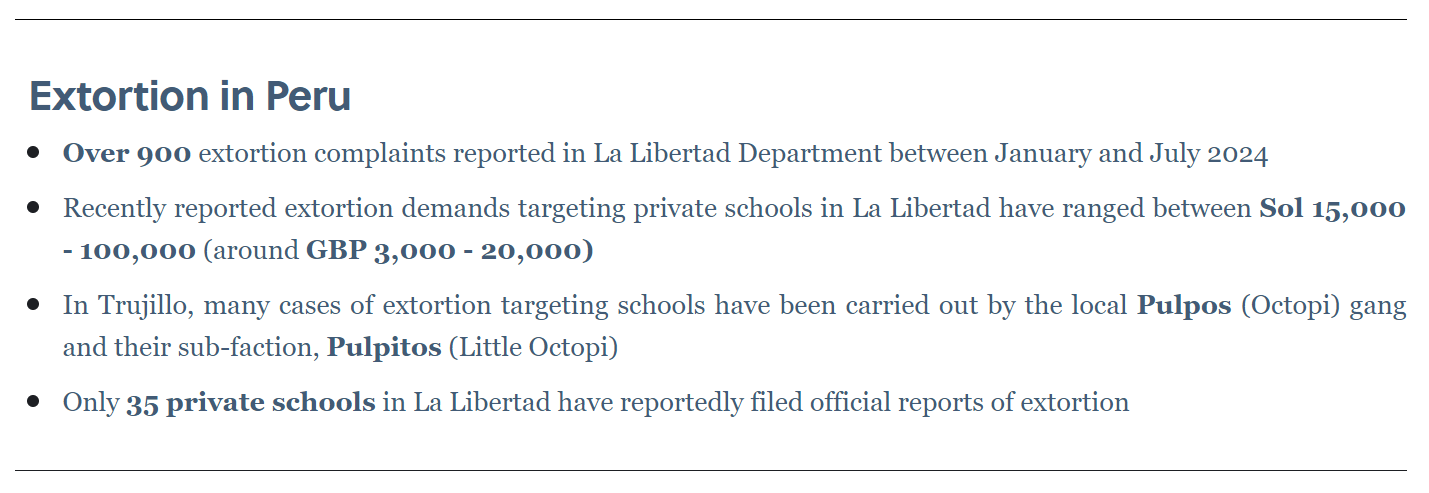

Amid a rise in organised crime in recent years, extortion has proliferated across all spheres of Peruvian society. Although there is longstanding precedent for criminal groups to target schools – including teachers and facilities – Peru’s deteriorating security environment and political instability has contributed to an increasingly permissive environment for such crimes to flourish. In the La Libertad Department and wider region, located in northwestern Peru, where this dynamic is prevalent, at least 150 schools have faced extortion, and 27 have suffered reprisal attacks by gangs in 2024 alone. Criminals have also directly intimidated leadership of these institutions, including politicians and business people.

With the lure of regular, higher tuition fees, and donations from wealthy patrons, private and international schools are particularly attractive targets. Criminals leverage threats of violence against children (especially in such a high concentration) to pressure school leadership into paying high extortion demands, and prevent them from reporting these events to authorities. Indeed, several such institutions confess to underreporting extortion incidents due to concerns over retaliatory attacks.

Violent Retaliation

In line with a national trend indicating the growing use of homemade explosive devices in extortion cases, schools in affected areas, like the city of Trujillo in La Libertad, have been subject to a number of reprisal attacks involving various types of grenades, bombs and other explosives. Criminals have also employed shooting attacks against facilities during class hours. This has threatened not only physical safety of the buildings’ occupants, but also these schools’ ability to operate. One school has suffered three attacks in 2024, two of which involved dynamite, and one in which criminals fired on the school’s entrance, prompting the institution to switch to virtual classes. Authorities have placed at least 20 schools in Trujillo under military protection since June 2024, while the wider La Libertad region has faced states of emergency, including restrictions on movement and assembly.

An illusive solution

Officials in La Libertad attribute growing extortion and associated violence to several factors, including increasing regional migration from Venezuela and Colombia, which has brought with it some criminal elements who have set up their own extortion rackets, and turf wars between Trujillo’s Pulpos gang and multiple rivals. They have called for additional military deployments, but security forces remain significantly under-resourced and are occasionally – including in Trujillo – implicated in extortive practices themselves. With a somewhat reactive strategy reliant on the indefinite deployment of military personnel to schools, this does little to address the root causes, or to protect associated individuals, like school directors, who continue to be directly threatened by violence, including at their homes.

Amid worsening political instability spurred by corruption, political infighting, and deteriorating institutions, national authorities are also ill-equipped to address the escalating organised crime situation that has enabled extortion to thrive. Proposed laws like Bill 5891, which would, in practice, promote greater impunity for criminals and restrict the criteria under which offenses could be considered ‘organised crime,’ threatens to further limit the toolkit to combat this phenomenon. Meanwhile, arrests of minors as young as 11 and 16 for staging violent attacks against schools signals further complexity in tackling and prosecuting such cases.

In the absence of a comprehensive strategy to deal with organised crime in the country, there are few signs that extortion against education institutions will abate. In the coming year, as wider security and political challenges persist, private schools will remain extremely vulnerable to exploitation by criminal groups.