Packs of Lone Wolves? The Global Far Right

A Shifting Threat

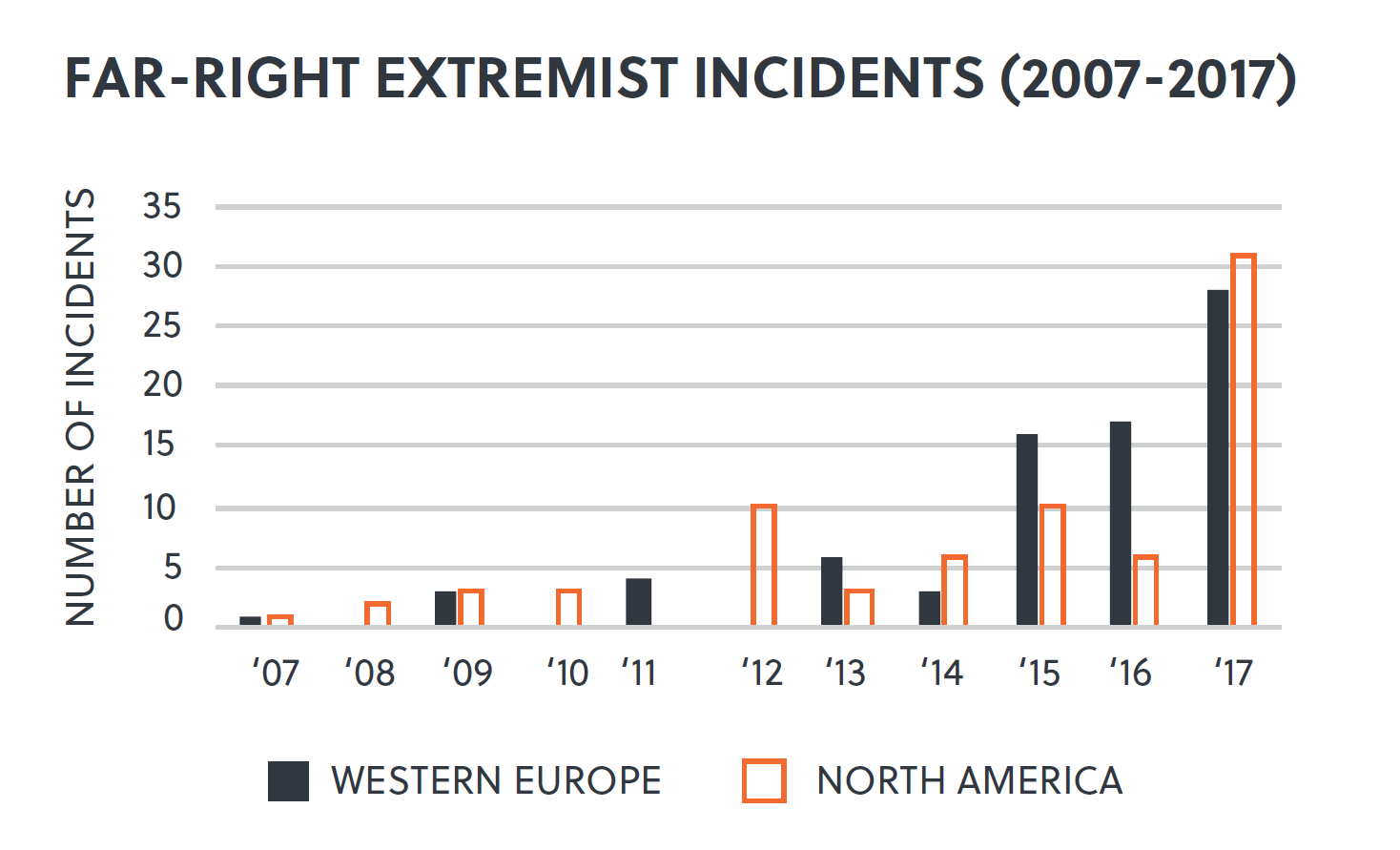

Many Western politicians and intelligence agencies are concerned about the growing terrorist threat posed by far-right and white supremacist extremists. While maintaining that Islamist militancy continues to pose the greater threat worldwide, many security agencies note that the number of far-right plots and attacks increased in recent years in North America and Western Europe. According to the Global Terrorism Database, Western Europe recorded 28 far-right incidents in 2017 compared with a single incident in 2007.

In the UK, for example, four of the 18 terrorist plots foiled by local law enforcement in 2018 were linked to far-right extremists. Meanwhile, UK authorities report that of the 7,318 referrals to the Prevent Counter-Radicalisation Programme between 2017 and 2018, 1,312 were linked to the far right, an increase of 300 percent from 2013. Indicative of the seriousness with which UK authorities take the growing threat, they announced in October 2018 that MI5, Britain’s domestic security agency, would take responsibility for monitoring domestic right-wing extremism. Police had previously been responsible for the task. The switch now means that, in the UK, rightwing extremism is officially designated an issue of national security as opposed to a law enforcement one.

Propaganda of the Deed

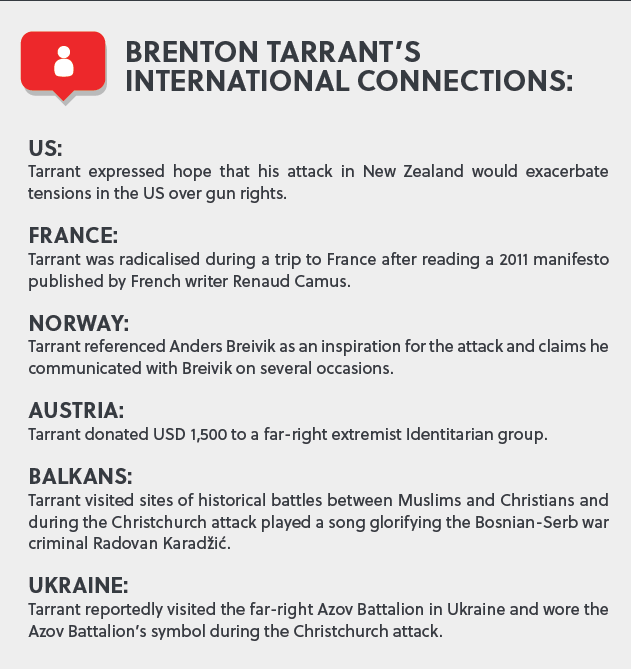

To date, most successful right-wing attacks have manifested as mass shootings carried out by lone actors. In most cases, the perpetrators attempted to spread their message through online networks. Analysts and scholars often refer to terrorist acts as a form of “propaganda of the deed,” or attempts to galvanise others into similar politically motivated actions. The internet opens up an array of opportunities for violent actors, including rightwing extremists, to reach global audiences. The March 2019 mass shootings at two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand, are the most recent example of this phenomenon of maximising coverage through social media. When Australian Brenton Tarrant, the perpetrator, shot and killed 50 people attending Friday prayers, he live-streamed the attack on Facebook for 17 minutes before moderators blocked it.

Facebook subsequently removed 1.5 million copies of the attack video from the platform. In the video, Tarrant referred to online meme culture, for example, by telling viewers to “subscribe to PewDiePie,” a YouTube star with an audience of over 90 million subscribers. These measures were seemingly designed to increase interest in the attack, and thereby inspire similar violent acts, ensuring it remained in the news cycle for as long as possible.

Following the lead of other far-right lone actors, such as Norwegian Anders Breivik, Tarrant published a manifesto online. In it, he railed against Muslims and immigration and again referred to online meme culture. The use of memes — a common online tactic — in the manifesto blurs the distinction between edgy pop culture and outright bigotry.

Evidence indicates that far-right lone actors are using the internet to form loosely organised networks.

Social media platforms, such as Twitter and Facebook, as well as online forums and chat rooms are increasingly used to amplify political messaging. Some gaming forums, for example, allow users to form private groups to talk about topics of mutual interest, and far-right groups then use these to share ideological talking points and in-jokes. These views generally go unchallenged, as most members of the groups already subscribe to the same ideological point of view, creating an echo chamber in which extremist political messaging becomes entrenched and normalised. These forums have the potential to connect disaffected far-right individuals from across the globe.

Global Networks?

Beyond simply inspiring one another through online propaganda, there is evidence that far-right lone actors are using the internet to form loosely organised networks. The most prominent example to date is provided by National Action, a prohibited far-right neo-Nazi terror group based in the UK. National Action initially used encrypted messaging applications and other social media platforms to communicate with sympathetic youths across the UK. After the group was banned in 2016, a Midlands cell of National Action refused to disband, and used Telegram to start forming what its own members described as “white jihadist cells.”

While there is little evidence to suggest far-right extremists have successfully created cross-border networks with other groups for organising attacks, several recent cases highlight how global links have reinforced, inspired and facilitated terror attacks by far-right lone actors. National Action has repeatedly referenced Anders Breivik, described by a leader of National Action as “the hero Norway deserves.” Meanwhile, Brenton Tarrant stated in his manifesto that he had become radicalised during a trip to France in 2017, where he read a thesis by a French right-wing writer which showed him that “in every French city, in every French town, the [Muslim] invaders were there.”

Private online forums, where members' ideologies tend to be uniform, create an echo chamber for entrenched extremist messaging.

Hand in hand with the proliferation of new technologies and platforms, opportunities for people to connect with like-minded individuals from across the globe have increased. Typically, the development of online communities around shared passions is harmless. In some cases, however, political extremism becomes the glue connecting particular online communities, potentially radicalising individuals for whom violence becomes a possible outlet for their beliefs.