Oil, oil, oil: The price of Libya's transactional politics

Amid a deteriorating local economy and at a time of rising global fuel prices, Libya’s oil exports are more crucial than ever. Yet, a protracted political crisis, disputes over the distribution of oil revenues and the reliance on local militias to secure oil infrastructure have led to a string of disruptions to oil production in post-revolution Libya. Oil as a financial life-line has meant its use as a bargaining chip in political powerplays has become commonplace. Now, with Libya in the midst of its latest political crisis, this system of transactional politics appears unwavering, with further disruptions to oil exports, and the inevitable impacts on the national economy, global oil supplies and commercial shipping operations at Libyan ports, increasingly likely.

NEW PLAYERS, OLD GAMES

Since 2011, rival political stakeholders have contested control over the country, and with it, control of Libya's oil infrastructure and revenues. With oil exports accounting for approximately 60 percent of the country’s GDP, they have long offered political stakeholders an influential bargaining chip during times of political disputes. This holds true for Libya’s latest powerplay between the Tripoli based Government of National Unity (GNU) and Sirte headquartered Government of National Stability (GNS). Having failed to hold elections in December 2021, the GNU’s mandate has now expired, and while outgoing leader Abdul Hamid Dbeibhah has refused to step down from office, GNS prime minister-designate Fathi Bashagha is keen to establish a new administration. Libya is thus once more divided between two rival governments and the control of its oil exports and revenues is being contested once more.

The protracted political crisis in Libya has also meant that no single stakeholder has a monopoly over the use of force. Instead, territorial control is divided among numerous militias, some of which are also tasked with securing national oil infrastructure. This has led to an arrangement in which militias align themselves with political stakeholders in return for lucrative security contracts. While convenient, this has made the country’s oil operations inherently vulnerable to political headwinds, with militias able to bring operations to their knees at the will of their political backer, or vice versa. Regional stakeholders such as the Petroleum Facilities Guard (PFG), controlled by the self-declared Libyan National Army (LNA), frequently join forces with local actors to amplify pressure on the government, disrupting oil flow and staging protests at oil facilities to push a particular agenda.

Oil as a financial life-line has meant its use as a bargaining chip in political powerplays has become commonplace.

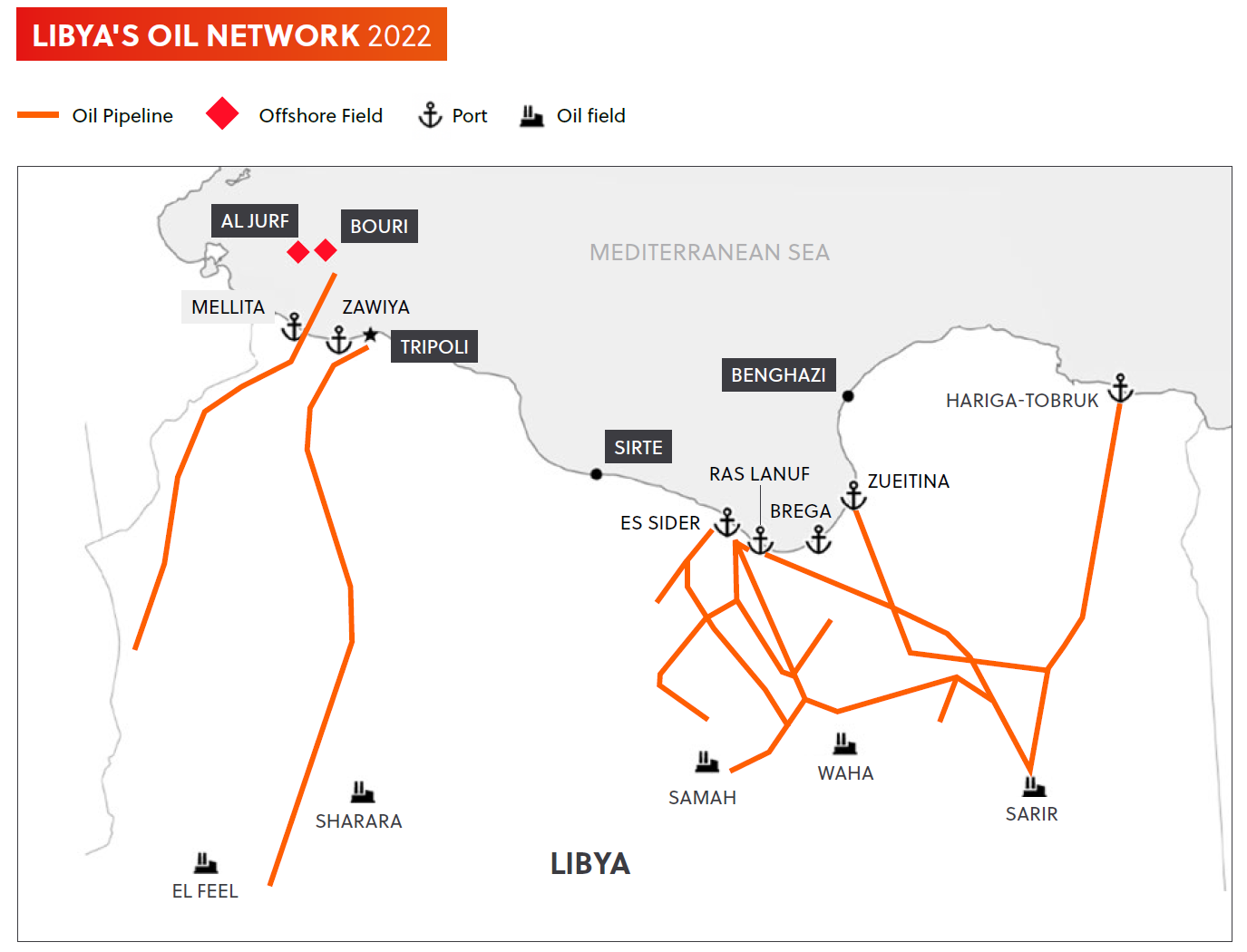

Already amid this latest political crisis, over USD 3.5 billion in revenue has been lost in recent months following prolonged blockades and protests at several oil fields, including the El Feel and Al Sharara facilities and at ports such as Zueitina, Marsa Brega and Mellitah, between April and July 2022. During the unrest, local protesters in southern and eastern Libya, largely aligned with LNA commander Khalifa Haftar, occupied the sites and demanded Dbeibhah step down from power in Tripoli. The demonstrators also demanded the resignation of Mustafah Sanalla, chairperson of the National Oil Corporation (NOC) – the state-owned entity responsible for Libya's oil production – over longstanding disputes regarding the distribution of oil revenues throughout the country. Haftar had recently pledged his support for Fathi Bashagha and used his influence among protesters to leverage their long-standing grievances with the Tripoli government to further his as well as Bashagha’s agenda. Disruptive measures were lifted in July following the removal of the NOC board, including Mustafa Sanalla, by Dbeibhah, who replaced Sanalla with Farhad Bengdara, an ally of Khalifa Haftar. The move was likely an attempt by Dbeibhah to appease Haftar, who persuaded protesters and militias to allow the reopening of affected oil fields.

TURBULENT TIMES AHEAD

Despite Libya’s oil production returning to full capacity following the end of the three-month blockade, the country remains divided, and oil production is likely to encounter further challenges in the near term. Until elections occur, the ongoing dispute between Dbeibhah and Bashagha is unlikely to be resolved, with the fractious political landscape only becoming more volatile. With a consolidation of the security forces unlikely under a divided government, militias will continue to hold sway over Libya’s oil and its exports.