No easy fix: The security crisis in Burkina Faso

Zambian-born Irish conservationist Rory Young was on a routine anti-poaching patrol in the Pama Reserve in eastern Burkina Faso on 26 April, accompanied by Spanish journalist David Beriáin and the documentary filmmaker Roberto Fraile. They were working on a film on the illegal wildlife trade and travelling in a group of 40 people, including security personnel, before suspected Islamist militants attacked and kidnapped them. Two days later, local government officials confirmed that the hostages had been killed.

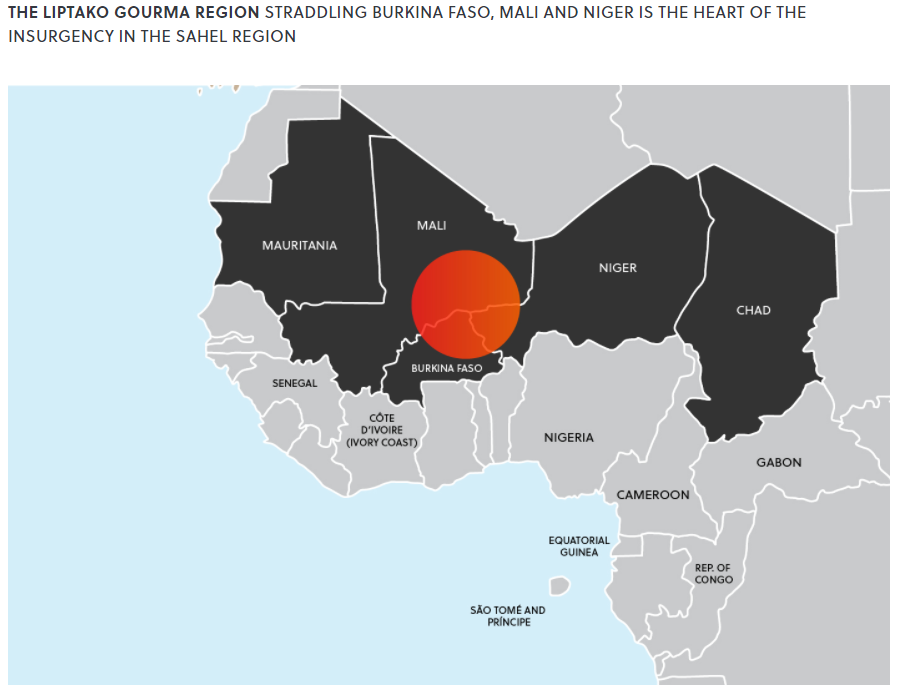

By early June, Burkina Faso’s security challenges were once again in the global spotlight. On 5 June, militants attacked Solhan village in Yagha Province, killing at least 160 people in what has become the highest-casualty terrorist attack in Burkina Faso’s history. President Roch Kaboré has since held emergency meetings to discuss ways of addressing the crisis. However, the government still lacks the security resources necessary to tackle the insurgency sweeping through northern, central, and eastern parts of the country since 2015.

Compared to foreign nationals, locals remain far more vulnerable to kidnapping.

HIGH-PROFILE KIDNAPPINGS

The incident in April was the latest in a series of high-profile kidnappings targeting foreign nationals in Burkina Faso since 2015. Although many kidnapping incidents go unclaimed or unreported, Islamist militant groups are the main perpetrators, namely the Jama’a Nusratul Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM), Islamic State West African Province (ISWAP), Ansaroul Islam, and their affiliates.

Kidnapping remains a major source of revenue for these groups in the wider Sahel, which typically demand large ransoms for foreign nationals and can keep hostages for extended periods. Although kidnapping foreign nationals loosely fit within these groups’ objectives, the reported kidnapping incidents in Burkina Faso since 2015 have mainly been the consequence of opportunistic attacks by groups affiliated with JNIM or Ansaroul Islam. Most foreign victims are those who are more likely to be operating in high-risk or remote areas such as employees of mining companies or aid workers. The existence of travel security arrangements is far from being a guarantee of safety; soldiers and forest rangers who were guarding Young’s anti-poaching patrol, for example, were outnumbered and outgunned by militants.

Compared to foreign nationals, locals remain far more vulnerable to kidnapping, with government officials, community leaders, Christian religious figures, businesspeople, and other civilians being the main targets. They may be kidnapped for ransom, but also to subjugate local communities.

PERSISTENT TERRORISM THREAT

In addition to kidnapping, locals must contend with escalating terrorism, which contributed to a significant portion of at least 1,400 conflict-related fatalities since 2015. Militant groups routinely attack local and international security forces and civilians, although commercial operations have not been spared. In a major attack in November 2019, for example, militants targeted a Canadian mining company’s vehicle convoy in Est Region, killing 37 people and injuring 60 others. And in January 2016, an attack on Splendid Hotel in the capital Ouagadougou claimed the lives of multiple foreign nationals. Alleged deals between the government and armed groups as well as Covid-19 restrictions on movement have resulted in a dramatic drop in conflict-related fatalities, from 413 people in March 2020 to just 41 in March this year. But, this reprieve was temporary; there have been seven major attacks in quick succession since April, including the highest-casualty terrorist attack in Burkina Faso’s history.

Most foreign victims are those who are more likely to be operating in high-risk or remote areas such as employees of mining companies or aid workers.

OUTLOOKSince the attack in Solhan, President Roch Kaboré has held emergency talks with government and opposition parties to discuss ways of tackling the crisis, although no immediate solutions are on the cards. The military – which is plagued by a lack of equipment, training, and funding, despite military assistance from France and the US – no longer has a presence in many conflict-prone areas, particularly in the north. France’s recent decision to end Operation Barkhane, its counter-terrorism operation in the Sahel, will also further embolden regional militant groups. Even at the height of Operation Barkhane, these groups have proved highly adaptive to such measures, leveraging their local networks and knowledge of the terrain. Until the government can supress the insurgency, focusing on governance and socio-economic dynamics as much as it focuses on security response, Young, Beriáin and Fraile are highly unlikely to be the last foreign victims of Islamist militancy |