Blood in the water: Joseph Kabila’s unsettling return to Congo

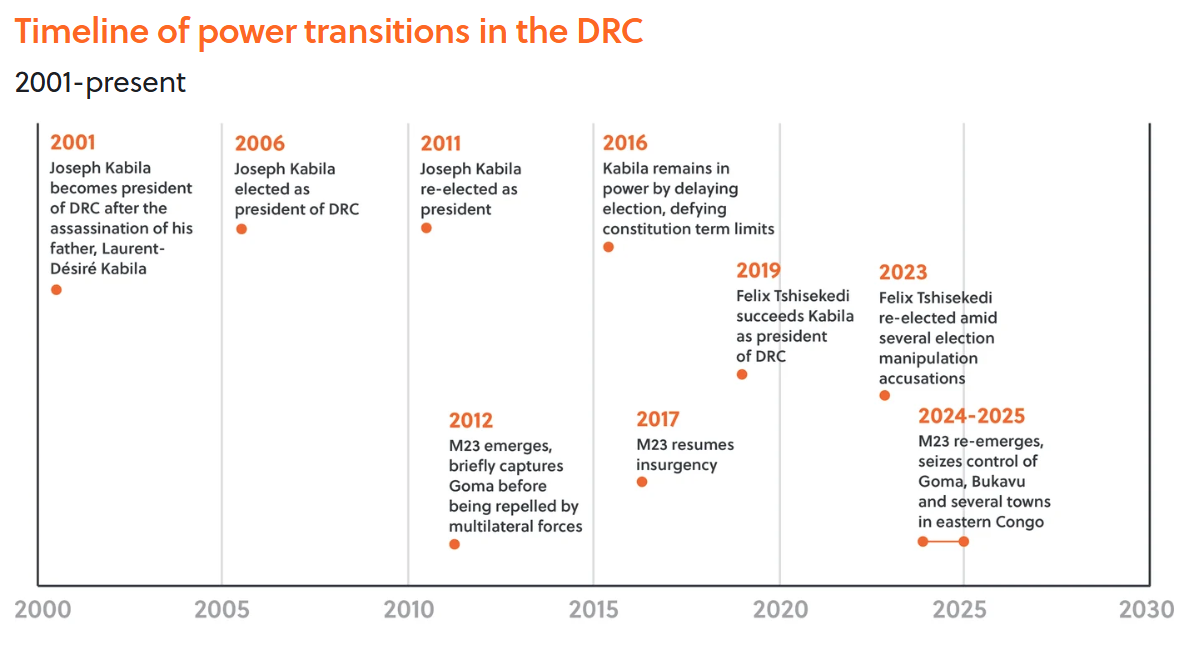

After two years abroad, former president Joseph Kabila (2001-2019) emerged in the M23-controlled city of Goma, capital of North Kivu Province, amid widespread rumours of a political comeback. Despite not confirming or denying said rumours, Kabila promptly began a fledgeling political campaign, taking meetings with local religious leaders allegedly aimed at resolving the ongoing war in eastern Congo. This, swiftly followed by current president Félix Tshisekedi’s attempts to suppress Kabila’s reach, have revealed deep-seated schisms within the DRC’s broader political environment. The ensuing political jostling threatens to exacerbate the ongoing political instability and the security crisis in eastern DRC.

A crisis of confidence in Kinshasa

Kabila’s return comes at an especially difficult time for the incumbent government, which struggles to maintain its control over the country and security situation. Tshisekedi’s administration has also found itself under the magnifying glass of international observers over the president’s 2023 re-election. Reports of irregularities and voter intimidation have cast a long shadow over his reported 70 percent vote share that year. Key opposition parties also remain critical of the sitting president, recently rejecting his attempts to form a multiparty ‘Government of National Unity’ and denouncing Tshisekedi’s proposal to review the country’s constitution as a ploy to extend his rule beyond term limits. Losing significant support, Tshisekedi finds himself in a notably weaker position as Kabila’s domestic political campaign begins to take shape.

Kinshasa’s response to Kabila’s return has signalled just how aware the administration and Tshisekedi are of their precarious grip on legitimacy and areas outside of the capital, perhaps fearing that – despite the banning of his party, the Parti du Peuple pour la Reconstruction et la Démocratie (PPRD) – Kabila will help bolster opposition against the government. The senate’s late May decision to revoke Kabila’s immunity and expose him to prosecution over links to M23, and a ban on media coverage of the former president until at least late August (largely ignored by the PPRD) further underscores this sentiment.

A new power in the East?

Kabila’s return also threatens to complicate fragile peace efforts in eastern Congo, with the government and Rwanda – accused of backing M23 – having just recently signed a provisional peace agreement on 19 June. As a major (albeit polarising) political figure, Kabila’s presence in Goma – including late May talks with religious leaders in the presence of M23’s spokesperson – lends a veneer of legitimacy to M23’s rule. While Kabila’s representatives have taken pains to clarify that it is not an alliance despite the common goal of unseating Tshisekedi, there nevertheless appears to be an understanding between himself and the rebel group. M23 has shifted its stance from conquerors to rulers in Goma and Bukavu, the respective capitals of North and South Kivu, redeploying militants for policing, courts and immigration enforcement. The group’s growing consolidation of power and governance in the mineral-rich region could strengthen its position in negotiations, reducing the likelihood of a peace agreement that is favourable to the government. This would be a significant setback for Kinshasa, which has long feared the rise of alternative centres of power in the east due to decades of secessionist movements and rebellions—particularly because of the risk of permanently losing control over key mineral resources.

Meanwhile, as Kabila positions himself as a voice of peace and M23’s control entrenches, concerns have grown around loyalty issues within the DRC’s armed forces in the east, including after the government’s arrest of 29 mostly senior military officers accused of associating with the former president. The military has long struggled with separate chains of command due to successive failed implementations of Disarmament, Demobilisation and Reintegration (DDR) programmes fillings its ranks with poorly trained former rebels, and has further relied on local militia groups to fight against M23. However, the potential attraction of switching sides could facilitate further instability within the military that could leave the force even weaker in its fight against the ongoing insurgency.

Kabila the disruptor

Kabila’s decision to head to Goma rather than Kinshasa likely reflects his recognition that he currently lacks the support to establish a base in the capital. However, this does not diminish the significance of his return. A disruptive figure in Congolese politics, Kabila’s re-emergence adds another layer of instability to an already fragile environment – one that has unsettled officials in Kinshasa and threatens to exacerbate the ongoing crisis in the east.