Elections crossroads in Latin America: Chile, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Venezuela head to the polls

In November, elections swept Latin America. While some yielded surprising results, others followed a more predictable path. With Chile, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Venezuela still reeling from the social and economic impact of Covid-19, political stability will remain elusive in the coming year, as new and incumbent governments adapt to a post-pandemic environment.

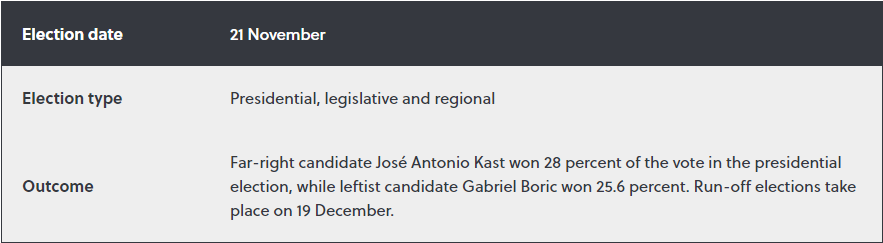

CHILE: NARROW RESULTS PROMPT UNCERTAINTY FOR DECEMBER RUN-OFF ELECTION

Chile’s elections took place amid a constitutional rewrite and ongoing protests over persistent socio-economic inequality.

Anti-government sentiment has increased since mass-protests in late-2019, fuelled by dissatisfaction over the Sebastián Piñera government’s inability to cushion the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on poor and middle-income communities. Grievances coincided with a re-emerging scandal over Piñera’s alleged corrupt deal in a local mining project. The Senate is unlikely to vote to convict Piñera, but such scandals highlight the underlying cause of social unrest – the uneven distribution of wealth between Chile’s political elite and the general population. This will continue to drive Chilean politics in the coming year.

Prospects for Chile’s post-election economic stability are also uncertain, particularly due to regulatory concerns in the mining sector. The draft constitution calls for stricter regulations on water, mineral and community rights, potentially undermining the sector’s regional competitiveness. Additionally, a controversial copper mining bill continues to make its way to the Senate, aiming to increase the government’s share of profits through higher mining taxes.

OUTLOOK

The close contest between Kast and Boric in the poll indicates that the population remains split in terms of candidate preference. But the subsequent run-off in December promises further political and economic uncertainty in the months ahead, regardless of who is elected. While Kast will likely retain much of the current economic and political status quo, including a pro-business stance and policy continuity in strategic sectors like mining, he is unlikely to pursue significant socio-economic change, the demand for which prompted protests and a constitutional overhaul in 2019. This could again instigate demonstrations by student groups, feminist collectives and other activists. Conversely, Boric may attempt to liberalise Chile’s political environment and roll back some of the more unpopular economic policies of the Piñera administration, although he will likely face resistance in parliament, potentially driving civil unrest among his constituents if he fails to implement promised reforms. Boric has also campaigned on a platform of ecologism and reducing mining emissions, but has not clarified on how he intends to tackle the mining sector. This confusion has already shaken investor confidence in the sector.

Other issues will drive further unrest, including inflation, a lack of access to affordable services and any discontent over the draft constitution. Such grievances will likely result in more protests and clashes with carabineros in urban centres in the coming months. Anger over corruption persists, and anti-government sentiment could escalate if new corruption scandals emerge.

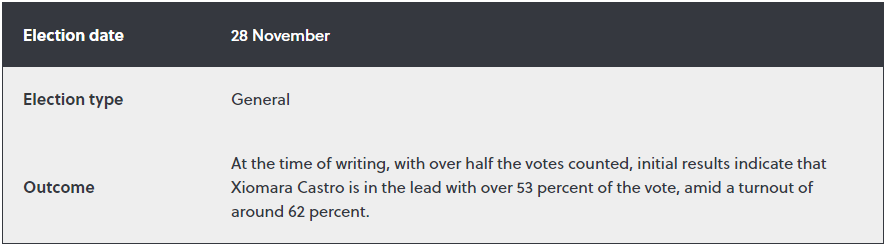

HONDURAS: A TURN TO THE LEFT

Since the coup against former President Manuel Zelaya in 2009, Honduran elections have been characterised by a lack of credibility, widespread disinformation campaigns, and high levels of politically-motivated violence. Between December 2020 and October 2021, there have been 27 murders, 18 acts of coercion, six threats, 11 assaults against political figures and activists, and at least one kidnapping. Such violence was evidenced in the recent assassinations of Cantarranas' mayor and opposition candidate, Francisco Gaitan, and Luis Casaña, a candidate for councilman in San Luis city. Both were fatally shot on 14 November during respective election rallies. Meanwhile, government-circulated disinformation surrounding electoral candidates prompted the UN coordinator in Honduras to warn against inciting hatred and violence via social media. Against the backdrop of opposition and voter intimidation, it is almost surprising that Castro, a member of the Libertad y Refundación (Libre) opposition party and spouse of former president Zelaya, secured an election victory.

OUTLOOK

The Castro government will face some opposition from the conservative Partido Nacional’s (PNH) supporters, who are likely to reject her socialist policies. These include switching diplomatic ties from Taiwan to China, as well as a proposed constitutional rewrite. But despite the usually fragmented opposition’s decision to unite behind Castro for the election, she will face significant difficulties in implementing such radical policies in Congress, particularly as each opposition bloc will likely default to infighting and pursuing their own agenda. Persistent corruption and economic mismanagement also means that Honduras lacks the fiscal capabilities to address ongoing socio-economic issues worsened by the pandemic. This includes an inherited energy crisis, and public debt that the International Monetary Fund expects to rise to 58.7 percent of the GDP in 2021. Medical experts have also warned that the country will face a fourth wave of Covid-19 infections after elections amid insufficient efforts to secure voting stations, which will hinder efforts at economic recovery in the coming months.

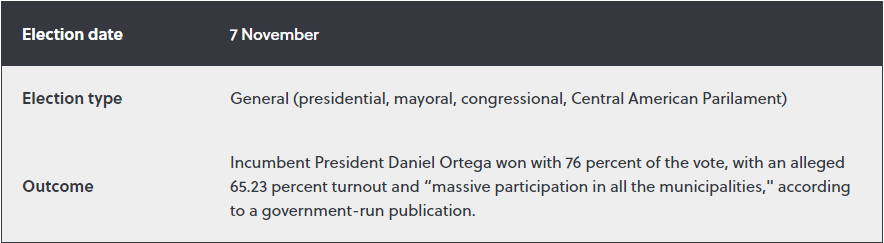

NICARAGUA: OPPOSITION CRACKDOWN YIELDS A PREDICTABLE OUTCOME

The vote took place following Ortega’s crackdown on opposition candidates. At least six candidates were detained ahead of elections, leaving five weak challengers to the incumbent president. Ortega also rounded up prominent critics, opposition leaders and activists, placing them under investigation for alleged national security concerns.

The government further leveraged its soft power resources in the form of mass-disinformation and misinformation campaigns. Social media platforms like Facebook and Instagram claimed to have removed over 1,000 government-backed accounts that served to amplify pro-government and anti-opposition content. Despite supposedly high participation rates, Urnas Abiertas, a civil electoral observatory group, reported abstention rates of over 80 percent.

OUTLOOK

2022 is unlikely to see a significant change in Nicaragua’s political or security landscape. President Ortega, now in his fourth consecutive term, has again demonstrated that challenges to his incumbency will not be tolerated. The military remains loyal to the government and fear of another crackdown, as was the case in 2018, will contribute to opposition activists’ reluctance to demonstrate in the coming year. Should anti-government sentiment drive another round of retaliatory protests, the associated crackdown will likely be swift and violent, manifesting as mass arrests, forceful dispersion and likely casualties. Ortega’s continued rule may offer a measure of political certainty and policy continuity, but widespread poverty, including food insecurity, will continue to strain regional resources as Honduran citizens look to exit the country in the coming year.

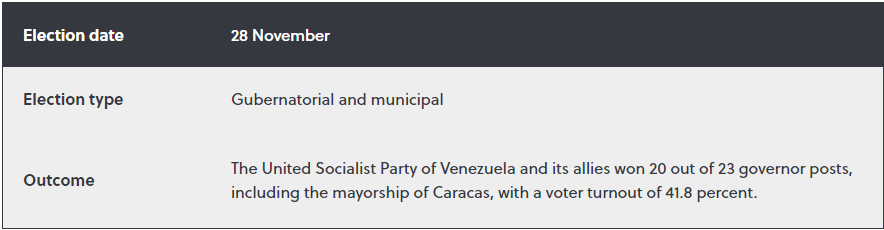

VENEZUELA: MADURO CLINGS TO POWER SURROUNDED BY SOCIO-ECONOMIC COLLAPSE

There was some optimism for the integrity of the poll when opposition parties re-entered elections after boycotting since 2018. Even the National Electoral Council, Venezuela’s highest election authority, yielded to international pressure and added two opposition members to its five-member board. But these developments were dampened by opposition candidates’ lack of resources and inability to unite over an agenda beyond seeking regime change

OUTLOOK

Venezuela’s socio-economic landscape will remain unstable as Maduro clings to power in 2022. Opposition factions’ defeat will further decrease the potential for any significant democratic reforms or competition in the 2024 elections, although widespread protests over poor service delivery will persist amid continued economic collapse and hyperinflation. With the National Assembly and military largely loyal to Maduro, it is unlikely that opposition supporters will be able or willing to mount a second attempt at a revolution, given the ultimate failure of former congress leader Juan Guaidó’s efforts, which had international backing. Prospects for improvement in Venezuela’s socio-economic situation are slim as Maduro lacks the will to implement structural change.