Complex Emergencies: Conflict and disease in the eastern DRC

CONFLICT AND EBOLA

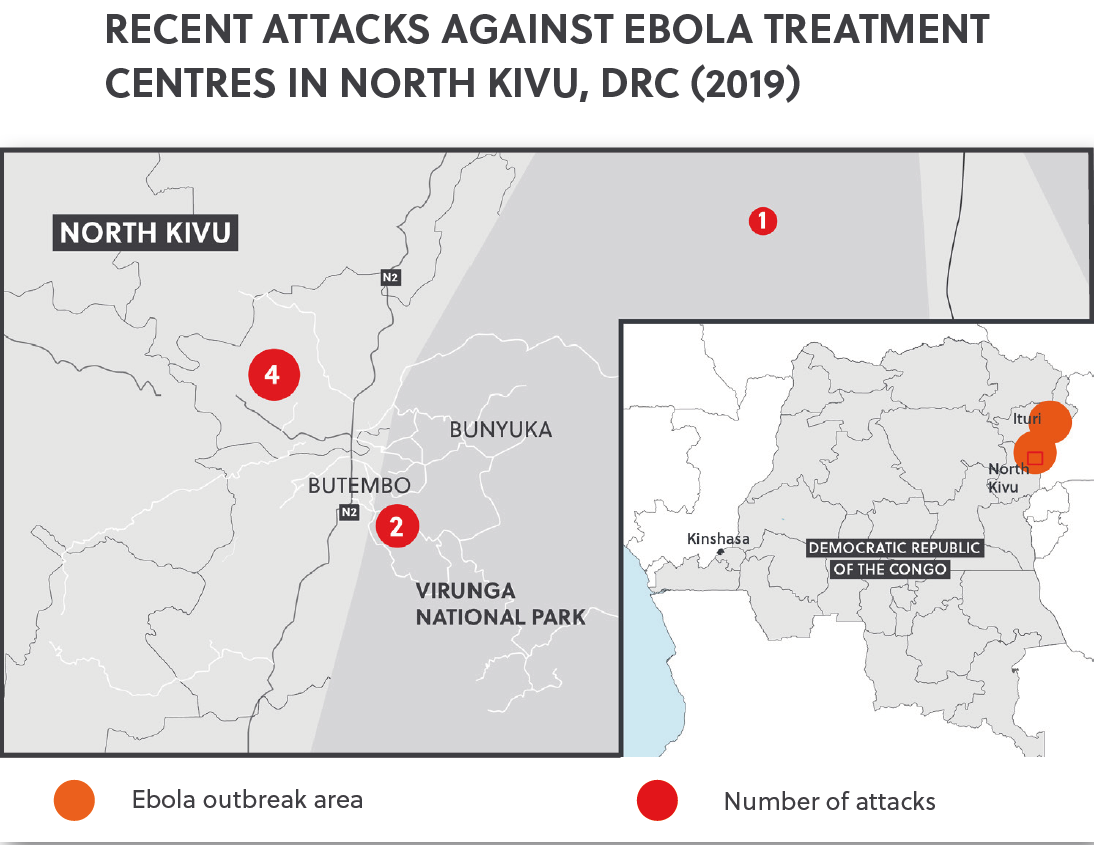

Over the past month, clashes between militant groups and security forces have increased in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), specifically in the North Kivu and Ituri provinces. While fighting is not new here, coinciding attacks on medical treatment centres combating the ongoing Ebola outbreak in Butembo and Beni in particular have exacerbated the situation. Since January 2019, there have been 42 attacks on health facilities and at least five healthcare workers have been killed thus far. These attacks have forced non-governmental organisations such as Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) to close treatment centres, suspend response operations and evacuate international staff. In May, local medical responders threatened to strike unless security measures were improved.

WHO IS RESPONSIBLE?

Over 100 rebel groups operate in the eastern DRC. While the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), an Islamist militant group known for attacks on security forces and communities alike, receives much media attention, various smaller militia operate throughout the region. The attacks against medical centres point to renewed activity by the community militias, known collectively as Mai-Mai. For example, on 27 February, a nurse and a police officer were killed when Mai-Mai militia clashed with security forces after setting fire to an Ebola treatment centre in Butembo. Following this, on 9 March, security forces killed one Mai-Mai militiaman and injured another after a separate attack on a treatment centre in Butembo.

Initially formed to defend communities during the DRC’s civil wars, these groups today comprise loosely connected subgroups and ethnic factions, each independently controlled by a leader. Given the autonomy exercised by individual leaders, it is often difficult to determine the exact intent of each Mai-Mai group. Yet, in recent months several Mai-Mai groups have come to threaten Ebola response operations.

WHY TARGET EBOLA RESPONSE OPERATIONS?

Rebel attacks against medical and other facilities are fairly common in the DRC and are typically linked to rebels seeking to loot supplies. While such a motive cannot be discounted in the latest attacks, coinciding rhetoric by Mai-Mai leaders as well as in local media reports, points to a more targeted campaign. Specifically, the World Health Organisation has warned that the Ebola outbreak has become politicised. The latest Ebola outbreak coincided with the general election in December 2018, which was postponed in Butembo, Beni and nearby Yumbi over concerns that a high concentration of people at voting stations would aid in the spread of the virus. Local stakeholders claim the voting postponements were a government ploy to prevent people from voting. Meanwhile, security forces, co-opted to aid coordinated vaccination programmes in 2017 and 2018, have been accused of intimidation, sowing mistrust among communities. This mistrust has been worsened by the medical need to burn the deceased to stop the spread of disease.

Misunderstandings and cultural beliefs are also likely contributing drivers of the attacks. On 19 April, Mai-Mai militia attacked a Butembo-based clinic in the Catholic University of Graben, which aids the World Health Organisation’s operations. According to witnesses, the attackers claimed that the outbreak had been fabricated, and that doctors caused patient deaths. Furthermore, Mai-Mai chieftains often control the ability of aid groups to access afflicted communities and are likely to exert some influence over community perceptions of treatment centres and staff.

THREAT TO AID AGENCIES AND HEALTH WORKERS

Amid this emerging intent to target Ebola response operations, health workers and humanitarian personnel are increasingly vulnerable to attack. The security vacuum in Ebola-affected areas, a consequence of a limited government presence, has further exacerbated this insecurity. Temporary clinics are particularly vulnerable as these facilities tend to be unguarded, while community leaders typically only allow a small number of aid workers to access affected communities, often without security escorts. Confrontations between security forces and attackers pose a further threat of damaging vital infrastructure and medical equipment.

OUTLOOK

The conflict in the eastern DRC is protracted and entrenched. Despite government and international efforts to resolve the now splintered war, fighting in the region continues to fluctuate as new rebel groups form and new localised agendas develop. Combating an Ebola outbreak in such a complex environment was always going to prove challenging. However, the latest attacks, which are unlikely to cease, present yet another obstacle to preventing the spread of disease.