Ukraine in Africa: Lessons from the Mali miscalculation

On 27 July, Tuareg rebels claimed they had killed 47 Malian soldiers and 84 mercenaries from the Russian private military company Wagner during clashes near the Malian town of Tinzaouaten. With reports from afar that Ukraine had allegedly helped the Tuareg coalition, the Cadre stratégique permanent pour la paix, la sécurité et le développement (CSP-PSD), involved in the attack, Mali and its neighbour Niger were quick to sever ties with Kyiv. The extent of Ukraine’s support for the rebels is up for debate, but the incident highlights that the consequences of the Russia-Ukraine conflict are far-reaching. Since the start of the war, Kyiv has sought to bolster its diplomatic efforts and other initiatives in Africa, which some have argued is a clear attempt to disrupt Russia’s influence on the continent. However, as the fallout from the Mali incident shows, there are clear risks attached to doing so in a manner that matches Russia’s increased military involvement on the continent rather than pursuing a more diplomatic path.

Ukraine plays catch up

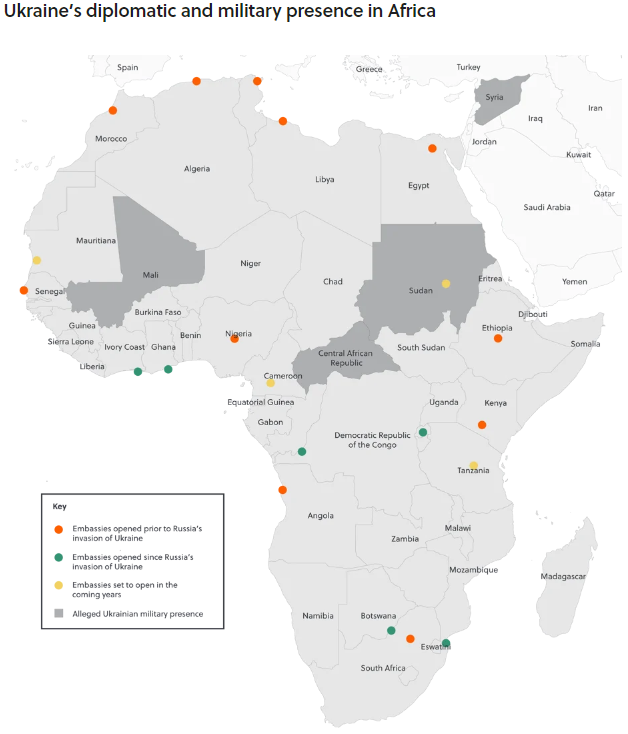

Before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Ukraine had limited reach within Africa, having opened only eight embassies on the continent since gaining independence in 1991. In contrast, Russia has been able to retain legacy ties between African liberation movements and the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), and in recent years, it has provided military support to help prop up military juntas and authoritarian governments such as those in Mali and the Central African Republic, as well as paramilitary organisations like the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in Sudan.

Ukraine’s diplomatic efforts in Africa, meanwhile, have only recently gained momentum following Russia’s invasion. Kyiv’s strategy now includes the establishment of new diplomatic missions – such as the six new embassies opened in 2023, including in Rwanda, Mozambique, and Botswana – and continuing the delivery of Ukrainian grain to countries like Sudan, Somalia, and Ethiopia as part of the humanitarian campaign “Grain from Ukraine.” Additionally, Ukraine is focusing on expanding economic cooperation in the continent, particularly in the agricultural and technology sectors.

Kyiv will be hoping these efforts bear fruit, considering its vested interest in strengthening ties on the continent. The long-standing policy of non-alignment in several African states has led many to avoid taking sides in the Russia-Ukraine conflict. For instance, following the invasion, only 28 of the 54 African member states voted to condemn Russia’s actions in the UN General Assembly, while 17 abstained. With African countries comprising a sizeable bloc in the UN, there is a clear diplomatic objective for Ukraine to expand its footprint and build a network of allies in Africa. Further, considering Egypt is the only African country ranking among Ukraine’s top 10 trading partners, there are also economic opportunities to improving and growing ties with African players.

Following Russia’s lead?

The benefits of Ukraine’s increased presence in Africa are evident, but attempting to mirror Russia’s strategy of deepened military involvement carries significant risks. Already, the incident in Mali has damaged Ukraine's reputation in West Africa. This was highlighted by the response of regional governments, particularly Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), which emphasised the need to avoid a new proxy conflict and stated Ukraine’s alleged involvement amounted to "foreign interference that threatens peace and security". Additionally, the volatile and unpredictable security situation in countries like Mali makes choosing sides a challenge and Ukraine’s alleged support for the CSP-PSD has had unintended consequences. Days after the attack, reports emerged that the Al Qaeda-affiliated group Jama'at Nasr Al Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) had fought alongside the rebels. The negative regional response and the revelation of an internationally designated terrorist group’s involvement in the attack likely prompted Ukraine’s foreign ministry to later deny it had a hand in the operation. However, by then, Russia had already capitalised on the situation, and has accused Ukraine of supporting terrorist groups and opening a second front on the continent.

Still finding its feet in Africa

Ukraine’s miscalculation in Mali suggests it is still finding its footing in formulating a clear, coherent, and constructive African policy. A series of media reports, citing Ukrainian intelligence sources, claim that Ukraine has targeted Russian and Wagner forces in countries including the Central African Republic, Sudan, and even Syria over the past year through special forces operations, drone attacks, and collaborations with local groups. While these reports have not been independently verified, they suggest that some elements within the Ukrainian administration, particularly in the security services, are eager to demonstrate their ability to strike Russian interests beyond the Ukrainian battlefield, especially in regions where Russia has invested heavily and maintains a strong presence. However, the risks associated with this approach seem to conflict with the more methodical and cautious strategy adopted by Ukraine’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, led by Dmytro Kuleba, over the past two years. The challenge for Ukraine will be to ensure coordination across the government, safeguarding the hard-earned gains of Kuleba’s approach from being undermined by incidents like the Mali blunder.

Ukraine’s miscalculation in Mali suggests it is still finding its footing in formulating a clear, coherent, and constructive African policy.

The long road ahead

Admittedly, a long-term strategy of engaging in measured diplomacy will take time to yield meaningful results. Kuleba himself has said that Ukraine is yet to see a return on its investment. Additionally, Kyiv will have to overcome the obstacles of sustained Russian support in parts of Africa, or policies of non-alignment in others, before this can have a real impact on Ukraine’s needs at home. While these obstacles are formidable, overcoming them and maintaining the diplomatic course avoids the damaging downsides of trying to play Russia at its own game of military interventionism.