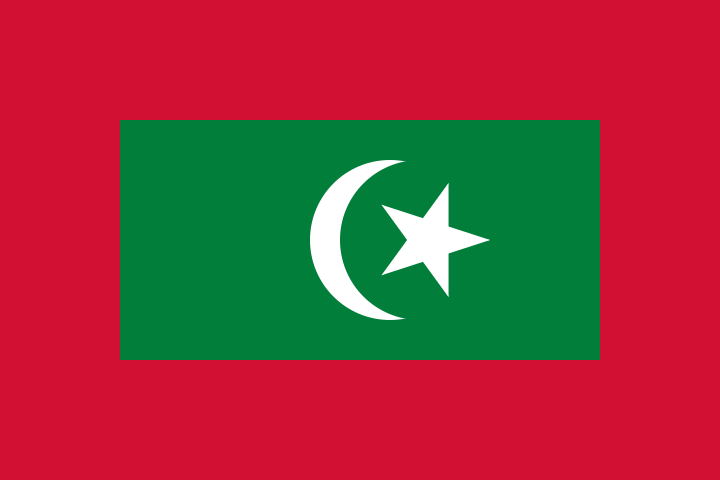

Tug-of-war: The Maldives and Sino-Indian competition in the Indian Ocean Region

India has thus far limited itself to diplomatic options, such as refusing to meet a Maldivian special envoy shortly after the state of emergency was declared. Nevertheless, China was adamant that India should not intervene in Maldivian affairs, and briefly deployed eleven warships to the eastern Indian Ocean, allegedly as a warning to India. While India did not directly respond to the incursion, as the Chinese ships withdrew shortly afterward, it has announced it will hold naval exercises in the region in March, including joint drills with China’s rivals such as Vietnam.

For China, the Maldives’ geographical position in the centre of the Indian Ocean makes it a valuable staging post for Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative. The initiative is a development strategy focused on creating a China-centred global trading network through various ambitious infrastructure development schemes, primarily in Central Asia and the Indian Ocean region. It was enshrined into the ruling Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) constitution at the 19th National Congress in October 2017, signalling Chinese President Xi Jinping’s centralisation of domestic power, and increasing the pressure on him to ensure the initiative’s success. The CCP generates political legitimacy through China’s continued economic growth and development, making the success of the Belt and Road Initiative a key concern and strategic objective for the Chinese government.

For New Delhi, China’s interest in countries such as the Maldives seems designed to encircle India, and could potentially undermine its access to global shipping routes. China’s long-standing partnership with Pakistan, India’s arch-rival, is an added concern. Pakistan is a key partner in the Belt and Road initiative and Beijing has committed approximately US$ 60 billion to Pakistani infrastructure development initiatives, including a port construction project in Gwadar, Balochistan. As such, India is currently pursuing closer relations with the United States (US), Japan and Australia – a collection referred to as the democratic quad – to jointly counter China’s regional influence. In February 2017 these countries announced their intention to establish an alternative to the Belt and Road; although, the specifics of this plan have yet to be hammered out. The four countries have also announced plans to cooperate on maritime security issues.

Given the incompatibility of Chinese and Indian interests in the region, the Indian Ocean will continue to be a source of geopolitical tension for both countries. Both will nevertheless do their utmost to avoid a direct military confrontation, as they are growing economies, and as such are dependent on Indian Ocean shipping routes for imported energy and access to markets for their manufactured goods. A military confrontation would jeopardise this flow. However, this dependency breeds anxiety, and both China and India will continue to keep a wary eye on each other, while jostling for influence with regional states in an attempt to gain geopolitical advantage.

Given the incompatibility of Chinese and Indian interests in the region, the Indian Ocean will continue to be a source of geopolitical tension for both countries.