To the ballot box: Key trends shaping 2024's election landscape | Political Violence Special Edition 2024

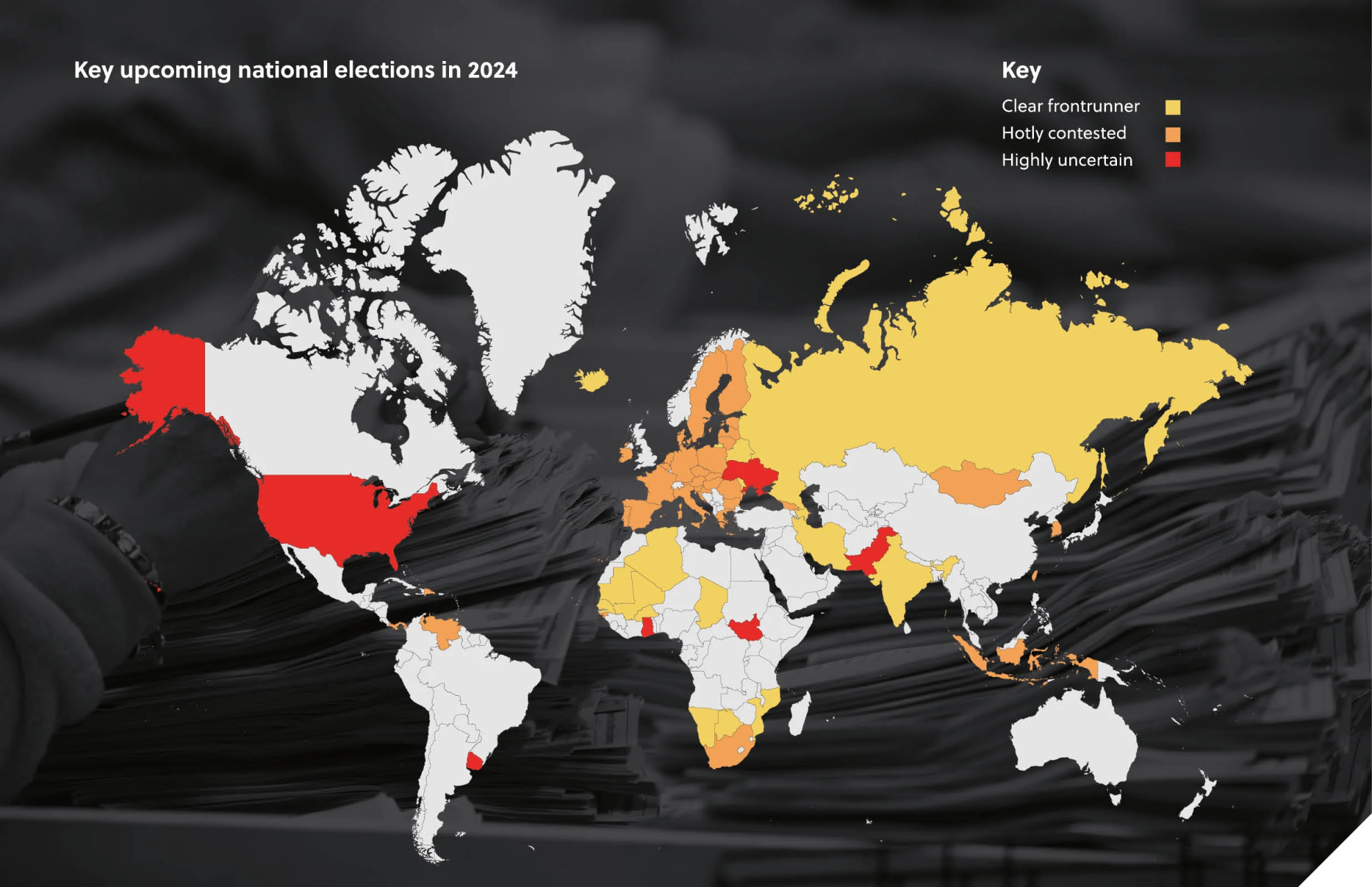

2024 is set to be the biggest election year in history, with over 70 countries going to the polls in some form, over 40 national elections taking place, and over 2 billion eligible voters taking part. Yet, with the world facing both geopolitical and economic headwinds, the outcome of many of these elections will be determined as much by their domestic contexts as by the global one. The ‘rise of the right’ is on the cards once more for several countries as voters confront the realities of domestic economic pressures, while other countries face an undecided electorate that could see increasingly fragile coalition governments attempt to take the wheel in the coming year. Meanwhile, for some, the prospect of an election will offer little in the way of real change as political heavyweights seek to secure a veneer of legitimacy to their grip on power. The year ahead will inevitably be one where the race to the polls, and determining the eventual victor, will keep election watchers guessing and potentially surprised at the result.

A return of the right (again)?

The end of 2023 saw right leaning libertarian Javier Milei secure victory in Argentina’s presidential elections, followed shortly by far-right populist Geert Wilders’s Party for Freedom (Partij voor de Vrijheid, PVV) win in the Netherlands in what has been termed an apparent return of the right in global politics. Although one swallow does not a summer make, with electoral setbacks to right-wing parties in Spain and Poland in 2023, these elections in Argentina and the Netherlands have set the stage for renewed focus on the right versus the left fight in upcoming votes. Nowhere is this likely to be more evident than the year of politicking that awaits the US ahead of the 5 November 2024 presidential election. Polling data suggests that voters anticipate a rematch between President Joe Biden and his predecessor Donald Trump, and as these opposing candidates fight it out over the coming months, increasingly aggressive rhetoric from their more hardline supporters is likely. Their campaigning comes at a time of growing political divisions in the country across a range of critical issues, from civil rights, social security and healthcare, to (foreign) defence spending and economic recovery. These, and other issues, all have the potential to encourage further widespread public demonstrations to which the US has become increasingly accustomed in recent years. With the election toward year-end – and a year is a long time in politics – the US faces several months of uncertainty. And, with the US’s political future determined as much by policy as it is by the president of the day, in the absence of strong alignment between the White House and Congress, such uncertainty will extend well beyond voting day.

Yet, the US is not the only jurisdiction navigating the growing divide between left and right. In the coming year, Europe will also offer a new battlefield for the potential return of the right. With key issues such as migration, the energy transition, the war in Ukraine and economic pressure continuing to dominate public debates, far-right parties have gained popularity on the continent. Giorgia Meloni has concluded her first year as Italian prime minister, the Sweden Democrats propelled to the second-largest party in parliament and while the centre-right National Coalition Party (NCP) secured a narrow victory in Finland’s April 2023 vote, the right-wing populist Finns Party leapfrogged the Social Democratic party into second place, forming a government coalition with the NCP and pushing the government agenda firmly to the right. Now, attention has turned to the outcome of the European parliamentary elections, scheduled for June 2024, where polling suggests far-right European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) and Identity and Democracy (ID) group will also enjoy some gains. An all-out victory for the far right is unlikely, but the growing popularity of these parties and the policies they advocate could see centre-right European People’s Party (EPP) coopt some of the more radical positions espoused by such players.

Undecided voters and coalition governments

For some countries, previous election guarantees may not withstand the challenge of 2024. In South Africa, the long-governing African National Congress (ANC) will face its largest challenge at the ballot box since 1994. The ANC’s declining popularity following enduring corruption, poor economic performance, and crumbling national infrastructure, has continued. It now looks increasingly likely that the ANC will fall below the 50 percent threshold for a majority government for the first time in South Africa's 30-year democracy. In the absence of a serious contender from South Africa’s main opposition parties such as the Democratic Alliance (DA) and the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), an ANC-led coalition government appears to be the most likely outcome of the May 2024 vote. While the election itself risks a surge in political violence comprising disruptive protests and political assassinations at the local level, particularly in hotspot areas in KwaZulu-Natal, the post-election period could be similarly volatile. Potential coalitions between parties like ANC/EFF and DA/ANC face major hurdles due to deep policy divides on issues such as land expropriation and economic empowerment policies. These rifts, coupled with inter-party disputes and mutual distrust, pose significant barriers to effective cooperation at a national level. Moreover, smaller parties' political opportunism has prompted fractious alliances at the municipal level over the past decade and raises concerns about their role in a national coalition's stability

and effectiveness.

These rifts, coupled with inter-party disputes and mutual distrust, pose significant barriers to effective cooperation at a national level.

Meanwhile, for Indonesia, coalition politics may offer a calmer way forward. The upcoming February poll will see a tough race between Defense Minister Prabowo Subianto from the Gerindra party, Governor of Central Java Ganjar Pranowo (of the nationalist Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle, PDIP) and former governor of Jakarta and independent candidate Anies Baswedan. Though Baswedan enjoys the backing of incumbent President Joko Widodo, there is yet to be a clear frontrunner. The race is likely to spark increased polarisation among the electorate that will need to be reconciled either through a balanced coalition or a particularly accommodating winner.

All to remain the same?

In other countries, upcoming elections enjoy clear favourites – though upsetting surprises cannot be ruled out. India’s governing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, is likely to secure a majority win by leveraging the vast support base that Modi has built through his personality politics, Hindu nationalism, and economic policies of welfare handouts and government subsidies. Nevertheless, Modi and the BJP have faced substantial economic challenges in recent years. Food and fuel prices have remained stubbornly above Reserve Bank targets in the years since the Covid-19 pandemic, and unemployment reached a two-year high of just over 10 percent in October 2023, with a high proportion (42 percent) of joblessness concentrated among educated youth. At the same time, prospects for a new opposition coalition seem promising. A united coalition of 28 opposition parties – under the acronym INDIA (Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance) – will seek to disrupt Modi’s third bid for office. Led by Rahul Gandhi from the Indian National Congress, the coalition is looking to leverage social issues, by promising a slew of welfare reforms, from healthcare and pensions to free electricity and bus fares. Civil unrest and acts of political violence have long been common features of all stages of India’s electoral and political processes and are likely to make a repeat appearance. In the months leading up to the polls, political rallies will abound, sectarian and Islamophobic rhetoric will escalate, and rival parties and factions will clash, as political and sectarian groups try to disrupt the playing field for their rivals.

Elsewhere, however, the opposition challenge is likely to be strongly quelled. Russia’s President Vladimir Putin won’t see much of a challenge to another term. Having pushed through the constitutional amendments that allow him to stay in office until at least 2036 and purportedly enjoying much support, Putin is widely expected to remain in office and, as such, continue the war in Ukraine and his belligerent posturing on the global stage. Meanwhile, elevated tensions in the Middle East off the back of the Israel-Hamas conflict have cast a shadow over preparations for Iran’s upcoming legislative elections. Many reformists are hopeful that with the elections coming in the wake of widespread protests in the country in 2022, Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and election authorities would be tempered in their efforts to disqualify less conservative candidates, but such moves could very well be impacted by events in Gaza and the regional and global response to them.