There's an app for that: Express kidnapping takes new form in Brazil

Widespread kidnapping for ransom began in Brazil in the 19th century, when gangs of cangaceiros – the Brazilian answer to Robin Hood – roamed the hinterland extorting wealthy landowners. In the early 20th century, a less romantic breed of kidnapper appeared, targeting Brazil’s new industrial elite for financial gain or political aims. Ideological kidnapping reached its apex in 1969, when Marxist guerrillas snatched the US ambassador from his car in Rio de Janeiro, exchanging his life for the release of 15 political prisoners. By the late 1980s, Brazil’s transition to democracy and broader wealth resulted in the decline of these showpiece abductions, and the emergence of a new type of kidnapping targeting urban professionals, tourists, and expatriates.

The constant churn in digital payment apps and their prioritisation of ease-of-use means their users are likely to remain a favoured target for kidnappers.

These so-called ‘express kidnappings’, in which victims were hustled to ATMs and forced to drain their bank accounts or briefly held until their families paid for their release, became endemic in Brazilian cities during this period. In the first eight months of 1991, Brazil experienced more than 80 prominent kidnappings, with many more express kidnappings going unreported. That year, Brazilians paid an estimated USD 30 million in all kinds of kidnapping ransoms. Some express kidnappings escalated into murder or violence. More often than not, they were rote, almost routine. By the late 2000s, the express kidnapping phenomenon was in decline due to increased legitimate job opportunities for urban slum dwellers, police crackdowns, new limits on ATM transactions, and increased security consciousness among targeted groups.

AN UNWELCOME RETURN

Now, express kidnappings are making a comeback. In the first six months of 2021, São Paulo, Brazil’s most populous state and the source of a third of its GDP, reported a 40 percent rise in kidnapping cases on the previous year, with state police investigating over 100 kidnapping incidents. This surge is being driven by an unlikely source: cashless digital payment apps, which enable users to instantly transfer funds via their mobile phones. These platforms have proved popular in Brazil, where traditional banks have a reputation for being slow, officious, and socially exclusive. As a result, the Instituto Locomotiva, an economic think tank, calculates that 34 million Brazilians lack access to basic banking services. In October 2020, the Banco Central do Brasil launched its own digital payment platform, PIX, to take advantage of the growing availability of cheap smartphones in order to open up digital banking to the country’s working classes. PIX proved a huge success, with approximately 100 million Brazilians now estimated to use the platform. Unfortunately, the features that make PIX attractive to its users also make it an increasingly lucrative revenue source for Brazil’s tech-savvy criminal gangs.

VOLUME OVER VALUE

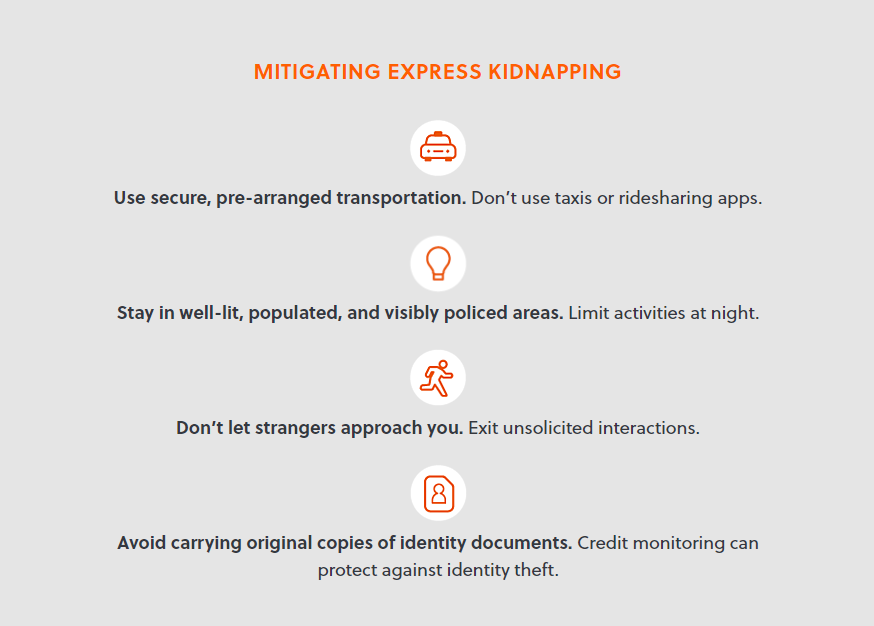

Like digital banking apps themselves, these kidnappings are disruptors on established models. Victims are accosted by their attackers, sometimes disguised as taxi drivers or police officers, and taken to isolated locations or driven around. Whereas the previous generation of express kidnappers had to transport their victims from ATM to ATM, with the attendant risk of detection, victims are now held and forced to make mobile transfers to digital accounts. Usually, the victim is released after a short time, although any kidnapping carries considerable tail risk of violence or death, particularly if things do not go to plan, or if perpetrators are challenged by police. In May, at least 25 people were killed in Rio and dozens of bystanders injured during a shootout sparked by a raid on a kidnapping gang. Often, the kidnappers will also steal identity documents, which are used to open a new set of digital bank accounts, causing ongoing difficulties for the victim. By the time the authorities are alerted, the stolen money has been withdrawn and the kidnappers have vanished. While affluent Brazilians, tourists, and expatriates continue to be favoured targets, the popularity of payment apps has increased the pool of potential victims, with criminals prioritising volume over value.

NO EASY FIXES

In September 2021, PIX announced several changes to decrease the platform’s utility to kidnappers, including a USD 200 transfer limit at night, when kidnappings are most likely to occur, and a minimum waiting time between transfers. Nonetheless, the constant churn in digital payment apps and their prioritisation of ease-of-use means their users are likely to remain a favoured target for kidnappers. App developers have resisted further regulation, arguing that security features that frustrate kidnappers increase the risk of kidnappings ending violently. On a broader level, the entrenchment of parallel criminal power structures that many Brazilians feared during the crime wave of the 1990s has come to pass, driven by a lost decade of economic stagnation, persistent inequality, and now Covid-19, which has killed almost 600,000 Brazilians and harshly underscored the ineptitude of the country’s institutions. Approximately five million Brazilians have fallen out of the middle class during the pandemic, and 80 percent of Brazil’s poorest people are now living on less than half their pre-pandemic income. Until Brazil’s deep structural challenges are addressed, they will continue to drive crimes of opportunism and desperation. Of these, digitally facilitated kidnappings are only the latest grim innovation.