The economics of unrest: Turkey's misguided economic policies and the potential for popular protests

A deteriorating global economy, the war in Ukraine and congested supply chains are causing rising prices around the world. In Turkey, however, the financial crisis – while compounded by external pressures – has its roots in far deeper structural issues initiated by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. The economic policies pursued by Erdoğan, focusing primarily on GDP growth, have resulted in periods of hyperinflation and currency depreciation several times over the past five years, directly impacting the spending power of citizens.

MISPLACED ECONOMIC POLICIES

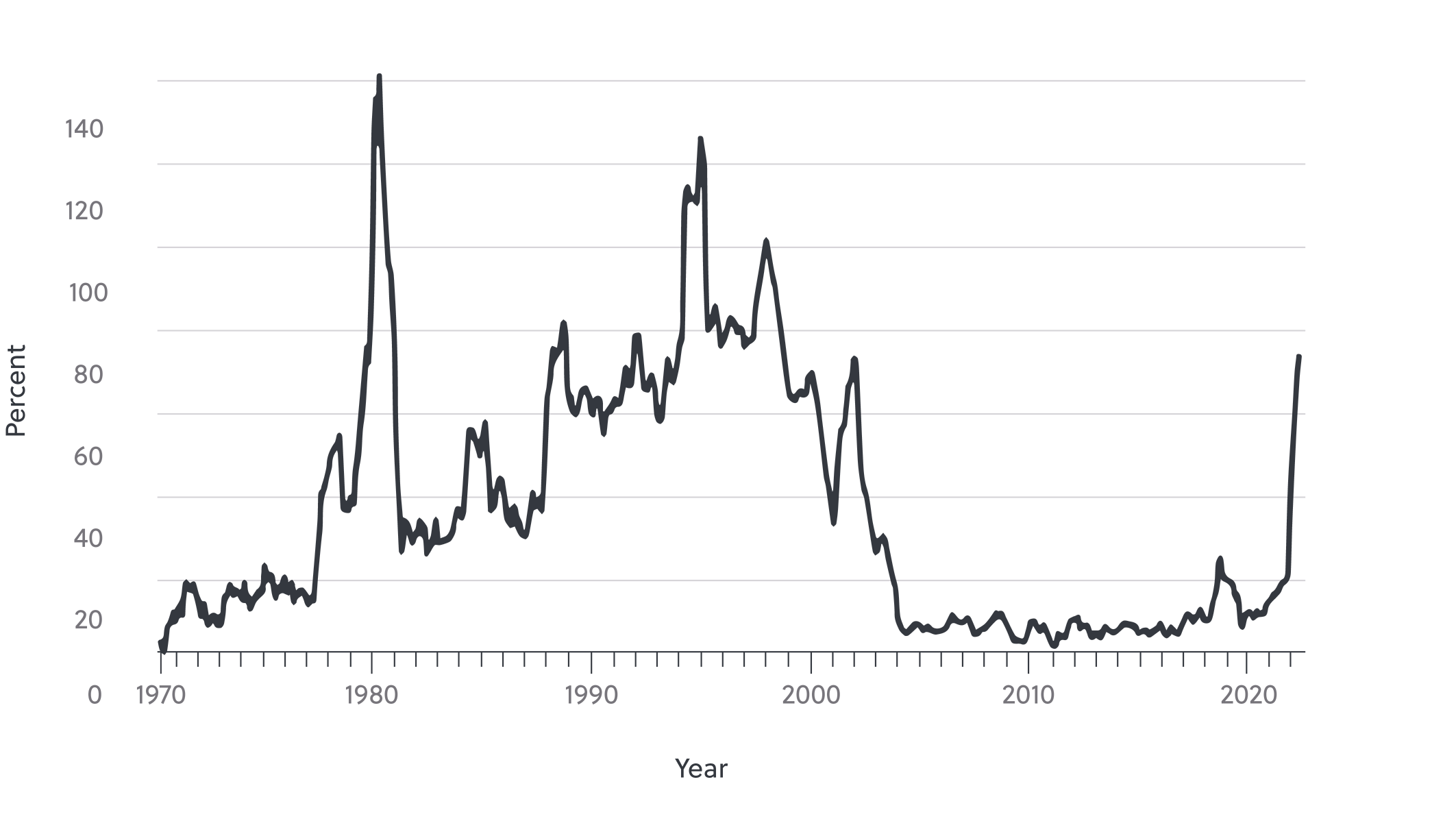

The global context aside, two main facets of Erdoğan’s policy have significantly contributed to the country’s current economic crisis. The first is that Erdoğan insists that low interest rates will boost economic growth and stem inflation. While this has resulted in rapid GDP growth, it has also led to a near 40 percent depreciation of the Turkish Lira against the dollar and, as at the end of 2021, inflation levels of 36 percent. Erdoğan’s low interest-rate ambitions have resulted in multiple changes to the Central Bank's leadership, as well as the loss of the bank's autonomy. At the time of writing, the Central Bank has decided to maintain interest rates at 14 percent, despite Erdoğan calling for interest-rate cuts to resume, but it is unclear whether the bank will be able to hold this position.

With inflation reaching a shocking 73.5 percent year on year in May, the spending power of Turkish citizens is plummeting.

Secondly, Turkey is heavily dependent on foreign imports and investment, particularly in the energy sector. Severe depreciation of the Lira, exacerbated by global inflationary pressures, means that the import of basic goods such as oil, gas, meat, fertiliser and metals has become extremely expensive. Erdoğan believes that a weak Lira will boost exports. But, with Turkish exports exports heavily reliant on imported raw materials and intermediate products for their production, and with inflation driving up production costs, currency depreciation is proving more damaging than good. Moreover, Turkey’s dependence on foreign loans, again coupled with hyperinflation and a depreciating currency, has meant that servicing international debt has become increasingly expensive, placing further strain on the economy and its financial institutions.

With parliamentary and presidential elections in June 2023, Erdoğan will be eager to avoid Turkey’s economic collapse. However, his policy appears to be to wait out the adverse global economic conditions, more inclined toward short-term measures that will placate investors rather than implementing long-term economic reform. In the meantime, soaring inflation is making the cost of basic necessities like energy, food and transport increasingly near intolerable for many Turkish citizens.

RISING RESENTMENT

With inflation reaching a shocking 73.5 percent year on year in May, the spending power of Turkish citizens is plummeting. In early February, anger spread across social media, and thousands took to the streets in protest against the steep increases that threaten businesses and households alike. It is increasingly likely that we will see sporadic protest action and demonstrations in the coming months, as inflation continues to soar, and opposition leaders shore up support ahead of the general election scheduled for June 2023.

Furthermore, resentment towards the over 3.6 million Syrian refugees living in Turkey is growing as the economic crisis deepens, and has the potential to drive further unrest. Some local nationals are increasingly blaming refugees for job shortages and rising rental prices, and polls suggest that the majority of Turkish citizens want refugees to be sent home. Although this discontent is currently restricted to social media, opposition leaders, particularly those on the far right, have been stoking this resentment through propaganda slogans and videos as a means to secure popular backing ahead of the 2023 vote.

LOOKING AHEAD

Although the Turkish economy has gone through several similar dips in the past years, the severity of the current financial crisis is undoubtedly worse than in 2018, and inflation shows no signs of slowing down. This is likely to remain a key driver of protest action in the coming months. Thus far, Erdoğan’s government has been successful in clamping down on mass action – as was on 31 May at a rally marking the anniversary of the 2013 anti-Erdoğan “Gezi” demonstrations, when police arrested 170 protesters and used tear gas to disperse the crowds. However, the upcoming elections provide a new opportunity for action. Already, a rally, attended by tens of thousands, was held on 21 May in support of Canan Kaftancioglu, an opposition leader of the opposition party, Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi (CHP) who was given a suspended sentence for insulting Erdoğan on social media. While this may suggest the beginnings of mass action, it also illustrates Erdoğans propensity for shutting down his opposition using the legal system. For now, Turkey-watchers are keeping a close eye on the growing socio-economic pressures that could bring with them a requisite catalyst for more sustained unrest.