The Case of the Missing Radioactive Material

THERE'S A MARKET FOR EVERYTHING

Sources of radiation are essential in many industries in over 100 countries. The most well-known use of industrial radiation is in medical applications, with the most potent of these sources being used in radiation treatment for cancer. Aside from medicine, radiological sources are used widely in the extractives industry, where various radiological materials are used for imaging, and testing the integrity of pipelines. Without these radioactive sources, many industries would not be able to perform basic functions that keep those industries running.

However, the security around these sources is generally poor, in particular when being disposed of or transported.

In 2016 alone, there were 189 instances of radiological material being stolen, lost or trafficked.

Whilst the disappearance of iridium-192 in Malaysia has made international news, there are many such instances passing under the international news radar. The UK Health and Safety Executive (HSE), reported that between 2003 and 2013, there were over 30 cases of radioactive sources going missing in the UK, a development branded as “disturbing” by nuclear industry expert, John Large. In higher risk jurisdictions, too, the disappearance of radiological material is a serious concern.

IRAQ

In Iraq, in 2016, an industrial radiograph - a tool used to test oil pipelines for structural problems - was stolen from a contractor working in Basra Province – an area of high criminal and terrorist activity. It was feared that the material was in the hands of militants operating in Iraq, and might be used to construct a ‘dirty bomb’.

KAZAKHSTAN

In 2017, Kazakhstani police arrested four men who were attempting to sell plutonium, which they had acquired from an industrial device. This followed an incident in 2013, in which a group were arrested in Karganda, Kazakhstan after attempting to sell cesium-137 for USD 250,000. They had stolen the material from an enrichment plant belonging to a mining company. This material had been kept by the perpetrators for 22 years.

MEXICO

In 2015, Mexican authorities issued an alert following the theft of an industrial radiograph during transportation. The radiograph contained iridium-192. This followed an earlier incident in 2013 in which a truck transporting a highly radioactive source, used for treating cancer, was stolen, as well as two similar incidents in 2012. These thefts prompted significant concerns that militants, or other extremist groups, might look to buy the materials from the thieves, which could be used in attacks

These examples are representative of only a small portion of the scale of the issue, and the IAEA are unable to determine how many successful transactions involving the sale of stolen radiological materials occur. However, the discovery of such instances clearly demonstrates the existence of a market for these= substances, and subsequently, the threat that presents to international security.

DIRTY BOMBS - A SERIOUS THREAT?

The greatest concern is that industrial radiological material may fall into the wrong hands, and be used to construct a ‘dirty bomb’, a type of RDD. A ‘dirty bomb’ combines a conventional explosive with a radiological source, and once detonated, it spreads the radioactive material across the blast zone, contaminating objects and people in the vicinity. However, in comparison to a nuclear weapon, where the radiological source is the main destructive power, a ’dirty bomb’ is more likely to cause physical damage via the initial explosion of the conventional improvised explosive device (IED) component. In fact, the weapon may not cause significant radiation damage, depending on the amount and potency of the material used, and the conditions of the environment.

Nevertheless, despite the low immediate risk associated with radiation from an RDD, the site surrounding an explosion would likely be contaminated by the radioactive material and require comprehensive decontamination procedures, at ‘significant time and expense’, according to the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission. In addition, compared to a nuclear bomb, a ‘dirty bomb’ would be far easier to construct and use. The fear that militants and non-state actors may acquire such a weapon is not unfounded; in 2003, British intelligence services assessed that Al Qaeda had managed to construct a ‘dirty bomb’ built from medical radiological sources. Whilst the device was never detonated, it has not been recovered. Although, its existence was corroborated by an Al Qaeda informant.

In addition to Al Qaeda, numerous other militant groups have demonstrated interest in acquiring radiological material to use as weapons, including Chechnya-based separatists, Lashkar-e-Taiba, and Aum Shinrikyo. In 2015, the FBI foiled an attempt by a dealer in Moldova to sell cesium-137 to the Islamic State (IS), and in 2013, an Indian army patrol discovered an IED containing 1.5kg of uranium in the Assam district. It is believed the United Liberation Front of Assam (ULFA) rebel group were planning to detonate it in an attack on Indian security forces.

WORST FEARS REALISED - THE CONSEQUENCES

In the event that a ‘dirty bomb’ is detonated in a populated area, it would have an immediate and significant impact on businesses and emergency services.

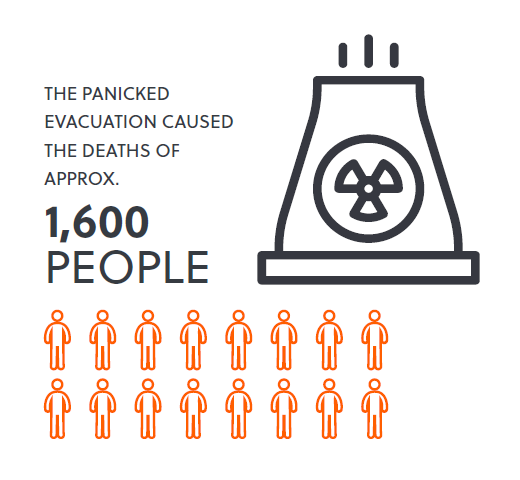

Whilst the detonation of the bomb’s conventional explosive would cause damage and injury, a key element of the radiological weapon is its psychological impact. Knowledge that the explosive contained radiological material would create mass panic in the vicinity and wider population, causing more injury and damage in the process. For instance, following the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant meltdown in Japan in 2011, the World Health Organisation found there were no acute radiation injuries or deaths among the workers or the public due to exposure to radiation. On the other hand, the panicked evacuation caused the deaths of approximately 1,600 people.

Following an attack, hospitals would have to implement screening and access control to prevent contamination of the hospital and its inhabitants. A lockdown of certain hospitals may even be necessary in the event of an influx of contaminated patients. This would severely hamper the treatment effort needed following such an attack.

The longer-term psychological impact of a ‘dirty bomb’ detonation would likely cause apprehension within the wider public to return to the scene, even following decontamination. Business continuity would suffer as a result for companies with operations in the area, as customers and staff are lost. These businesses would also have to be assessed for radiation exposure and potentially undergo a lengthy and costly decontamination process, before reopening (if able to at all).

Should the radiological material used in the attack have been the property of a private company, this would also carry considerable reputational risks and, potentially, punitive actions.

LEARN MORE

If you would like to know how your business could be affected by a CBRN event and how you can increase readiness, AXA XL’s nominated crisis management consultants, S-RM, can help.

S-RM’s Crisis Management services, include:

- CBRN Workshop

- CBRN Crisis Exercises

- Crisis Management Planning

- Business Continuity Support

- Crisis Communications Strategy Consulting