Terrorism in Russia: An enduring phenomenon

"We will pursue them everywhere,” said Vladimir Putin as Russia’s newly-appointed prime minister in September 1999, referring to Islamist militants who had carried out multiple bombings in Moscow, Buynaksk and Volgodonsk that killed over 300 people. The phrase has become symbolic of Russia’s heavy-handed counter-terrorism strategy pursued over the past two decades. On 1 July, for example, the Federal Security Service (FSB) arrested a Russian national in Moscow who was allegedly planning to carry out a bombing in the city. In another incident on 29 June, the FSB arrested an Islamic State (IS) sympathiser in Moscow and killed another in Astrakhan in southern Russia. They were allegedly plotting to stage attacks in crowded areas of both cities using firearms and knives. These incidents, together with the government’s 2020 statistics on terrorism showing an increase in attacks over the past few years, may create the impression that the FSB is struggling to contain the militant threat. However, statistics alone are not sufficient to analyse terrorism trends in Russia.

INTERROGATING THE NUMBERS

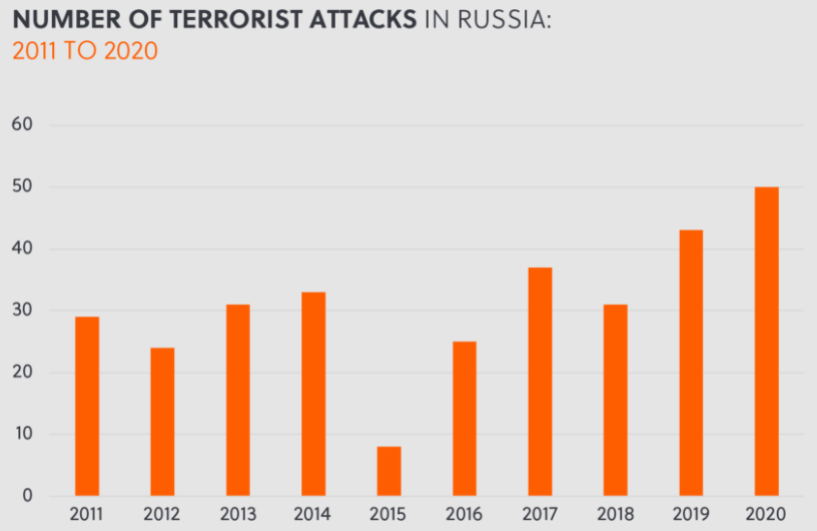

According to the government, there were 50 terrorist attacks in 2020 – the most since 2006 – compared to 43 attacks in 2019 and 31 in 2018. The authorities also recorded 2,342 terrorism-related crimes in 2020, a substantial increase from 1,806 incidents in 2019. Despite the reported increases, there has been an overall improvement in the security situation: while the number of attacks regularly fluctuated between 2011 and 2020, averaging slightly more than 28 attacks per year, this is a marked improvement from the previous decade, when there were around 206 attacks on average per year. The Global Terrorism Index (GTI), which ranks countries based on the impact of terrorism — particularly in terms of casualties – ranked Russia 39th out of more than 160 countries in 2020. It was ranked 9th in the 2011 index.

The rise in terrorism-related crimes also does not necessarily mean that militant groups have become more active. The government often uses anti-terrorism and anti-extremism laws to suppress opposition politicians, activists, and journalists. Such crimes can include a range of activities beyond attacks, such as participating in terror financing or recruitment, justifying terrorism, spreading terrorist propaganda and failing to report a terrorism-related crime considered to be an act of terrorism. But terrorism and extremism are also broadly defined. For instance, in July 2020, a court found freelance journalist Svetlana Prokopyeva guilty of justifying terrorism after she wrote an article on an October 2018 suicide bombing attack in Arkhangelsk. Such incidents can skew statistics as the authorities can label a peaceful dissident in the same manner as an armed militant.

The government often uses anti-terrorism and anti-extremism laws to suppress opposition politicians, activists, and journalists.

There is no indication that militants’ capabilities are improving or that their areas of operation expanding. Most attacks take place in the North Caucasus region – such as the republics of Chechnya and Dagestan – which have a long history of Islamist militancy. Incidents are typically low-impact and militants mainly target security personnel. There has not been a major attack in Moscow since the January 2011 Domodedovo Airport bombing, or in St. Petersburg since the April 2017 Metro bombing.

EFFECTIVE COUNTER-TERRORISM STRATEGY

Longer-term trends indicate that President Putin’s administration has mostly succeeded in bringing the terrorism threat under control. In the North Caucasus this has been achieved through an ongoing robust counter-insurgency campaign. The central government has also promoted pro-Moscow leaders who receive generous financial aid in return for their loyalty to the administration, which has helped to further weaken the insurgency. These strategies will likely continue to suppress militancy in the North Caucasus in the foreseeable future, preventing its expansion into urban centres.

Despite some local militants pledging allegiance to IS, and other cases of isolated IS-inspired attacks, authorities have effectively prevented IS from gaining a major foothold in Russia. In addition to frequent counter-terrorism raids, officials reportedly helped aspiring Russian Islamist militants to travel to Syria and Iraq in the mid-2010s. Many of these militants died on the battlefield, and observers’ fears that returning fighters would pose a threat to Russia have yet to materialise. Compared to several European countries, which did not have a longstanding terrorism problem like Russia, the latter has experienced fewer major IS attacks.

Although recent cases indicate that extremists still seek to attack populations in urban centres, regular FSB operations have targeted militant cells and limited their capabilities.

LIMITED THREAT TO URBAN CENTRES

Terrorism trends in Russia are unlikely to experience any major shifts in the coming months and years. Most attacks will continue to occur in the North Caucasus, and outside of major cities such as Moscow and St. Petersburg, as security forces are generally more proactive in targeting militant capabilities and preventing major attacks in populous urban centres. Despite this, there remain some flaws in Russia’s counter-terrorism strategy. Authorities have largely ignored the root causes of terrorism, like political and socio-economic marginalisation, particularly in the North Caucasus. The excessive use of force, including torture, extrajudicial executions and enforced disappearances enable terrorist propaganda and provides opportunities for militant groups like IS to radicalise and recruit locals. Authorities’ focus on clamping down on Islamist militants and political dissidents may also allow other actors to fly under the radar, like the May 2021 Kazan school shooter or the anarcho-communist Arkhangelsk suicide bomber. Until Putin’s vow to “pursue them everywhere” forms part of a more holistic counter-terrorism approach which also addresses the underlying drivers of terrorism, the threat of militancy will persist in the long term.