Security Challenges in Mexico's Oil and Gas Sector

The Mexican economy is heavily reliant on its lucrative oil and gas sector, with revenue generated by state-owned oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) historically accounting for approximately a fifth of total government income. The first quarter of 2018 saw Mexican oil tenders draw in almost USD100 billion in investments, with a number of heavyweight multinationals securing their position in Mexico’s recently reformed oil and gas sector. More than 100 oil development contracts have been awarded in the country since 2013, following energy sector reforms spearheaded by the Enrique Peña Nieto administration, which opened up the industry to foreign investment for the first time in over seven decades.

Nevertheless, Pemex’s oil output has been in decline, and a depreciating peso has put further pressure on the company’s profitability in recent years. By ending the firm’s monopoly on the sector, President Peña Nieto is hoping to revitalise Mexico’s oil and gas industry by boosting foreign direct investment to the country. Although the success of recent oil tenders demonstrates an appetite for the Mexican market on the part of foreign investors, the industry’s increasingly volatile security environment has raised concerns for new entrants.

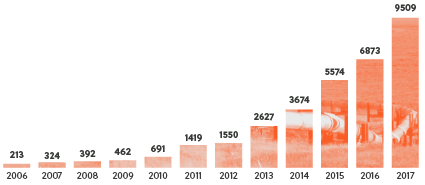

The primary security concern for the sector centres on Mexico’s endemic levels of fuel theft. In 2017 alone, Pemex reported 9,509 cases of illegal tapping along its network of pipelines, an almost twofold increase from 2015 levels, and an exponential increase from a decade prior, when only 324 cases were reported. According to company records, fuel theft has amounted to estimated annual revenue losses of USD1.6 billion, which also includes the cost of making necessary repairs to tapped pipelines. Fuel theft has historically resulted in significant infrastructural damage in this regard, with tapped pipelines catching fire for several hours at a time, or exploding because of tampering.

Although Mexico has been increasingly willing to deploy military personnel to patrol oil thieving hotspots, the scale and terrain of Mexico’s oil pipeline networks makes this a complex, expensive and frequently inadequate security measure.

FUEL THEFT MECHANICS AND MAIN ACTORS Although fuel theft has been a constant characteristic of the Mexican oil sector for decades, it was considered a relatively minor issue until the late 2000s. However, the turn of the decade saw a number of factors significantly boost criminal activity within the sector. Foremost amongst these has been growing interest from organised criminal groups (OCGs) in the fuel theft “trade”, including powerful groups such as the Zetas and Jalisco New Generation cartels. Oil theft has provided a highly lucrative and lower-risk alternative to drug trafficking for a number of OCGs seeking to diversify their revenue sources. Additionally, a heavy-handed government crackdown on organised crime has resulted in the subsequent splintering of a number of OCGs, with fuel theft providing smaller splinter groups with rife opportunities to secure contested financial and territorial resources.

Historically, the general modus operandi of fuel thieves in Mexico – locally known as ‘huachicoleros’ – has been to steal fuel directly from existing pipeline infrastructure using relatively simplistic methods and tools, such as a shovel, a drill, a hose and a fuel drum. Huachicoleros have also been known to steal wholesale from fuel trucks or Pemex storage units. They then sell the fuel with relative impunity to individual users or businesses at about half the price of what is available at local service stations, garnering significant community support in the process.

However, with OCGs now increasingly taking control of the fuel theft criminal enterprise, there has been a tangible escalation in tactics. Local huachicoleros have either been pushed out of their territories or incorporated into more complex criminal networks backed by OCGs. These networks are able to use more advanced machinery and explosives to penetrate oil pipelines, or deploy well-coordinated armed raids to steal from trucks and storage facilities. Furthermore, Pemex employees are increasingly victims of typical OCG intimidation tactics, including threats, extortion and murder. OCG networks are also better positioned to infiltrate and co-opt insiders. Pemex has already dismissed close to 100 employees for complicity in fuel theft, and a number of local politicians and security officials have been found guilty of facilitating, or directly participating in, fuel theft schemes. The scale of coercion and collusion within the oil theft enterprise have made tackling this specific security threat a particularly difficult task for authorities and corporate entities alike.

PIRACY OCGs are not the only criminal elements to expand their operations into the oil sector. Pemex has recently also become a prime target for piracy. According to Mexico’s Navy Secretariat, between December 2016 and January 2018, there were a total of 21 attempts made by oil thieves, often posing as fishermen, to board Pemex offshore oil platforms and ships operating in the Gulf of Mexico. Of these, a reported 11 oil platforms and ten vessels were attacked in the Bay of Campeche. Furthermore, two attacks targeted ships docked in the port of Dos Bocas, in Tabasco, with robberies, or attempted thefts, also taking place on vessels in Ciudad del Carmen, Las Coloradas and Atasta. Other than fuel, pirates have also been known to steal pipework, engines, aluminium, electrical wiring, copper, computers, communication equipment and cash from ships and oil platforms in the region.

GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION OF FUEL THEFT IN MEXICO Fuel theft is most prevalent in the centre and centre-east of the country, where the coastal oil and gas production of Veracruz is transported through the high concentration of pipeline infrastructure to, and through, states around Mexico City. Particular hotspots include the town of Salamanca in the state of Guanjuato, as well as the area known as the “Red Triangle” in the state of Puebla, encompassing the Tepeaca, Palmar de Bravo, Quecholac, Acatzingo, Acajete and Tecamachalco municipalities. Around 40 percent of fuel distributed from Mexico City runs through this zone.

FOREIGN INVESTORS PLACE THEIR TRUST IN MEXICO’S SECURITY RESPONSE, BUT IS IT ENOUGH? Oil theft predominantly impacts the refinery sector in Mexico, which is still wholly controlled by Pemex. However, the latter is increasingly seeking foreign investment to assist with much needed upgrades to its infrastructure. Furthermore, although Pemex has historically covered the costs of fuel theft targeting its pipeline network, some of these costs may be transferred to the private sector in future, as foreign investment accelerates over the coming years. Thus, supplementing local security initiatives with corporate security planning is likely to become a growing necessity for multinationals eyeing the Mexican oil and gas market. The entry of OCGs has seen oil theft in Mexico become an increasingly prevalent, lucrative, and violent component of the country’s black market. Although Mexico has been increasingly willing to deploy military personnel to patrol oil thieving hotspots, the scale and terrain of Mexico’s oil pipeline networks makes this a complex, expensive and frequently inadequate security measure. Furthermore, the deployment of military police has come under criticism following revelations by local media outlets that soldiers were executing suspected oil thieves on site. Meanwhile, OCGs continue to display impunity in the face of mounting security measures. In January 2018, for example, suspected OCG members killed the head of security for one Pemex’s oil refineries in Salamanca.

Companies considering investing in the many opportunities presented by Mexico’s increasingly liberalised oil and gas sector will undoubtedly have to contend with the very real security risks facing both their personnel and infrastructure. Prospective investors should therefore take appropriate steps to ensure a thorough understanding of the threat environment, and – where possible and appropriate – take necessary measures to mitigate these upon market entry.