Results Rejected: Jakarta's May 2019 Riots

Rejected Results Lead to Riots

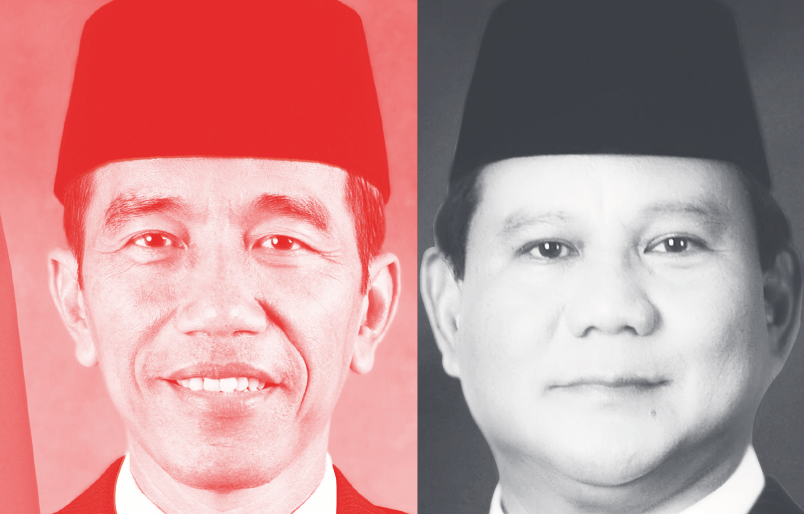

On 21 May, Prabowo Subianto, a former military general and leader of the Partai Gerakan Indonesia Raya (Great Indonesia Movement Party, Gerindra), rejected the election commission’s announcement that incumbent candidate Joko “Jokowi” Widodo won the April 2019 general election by a 10 percent margin.

In response, thousands of Prabowo’s supporters rampaged through central Jakarta for at least two days. Protesters attempted to storm the election commission’s office before setting fire to numerous vehicles, commercial properties, security checkpoints and one police dormitory. Rioters clashed with security forces, throwing bricks, petrol bombs and other debris at law enforcement personnel. Riot police responded with tear gas, water cannons and rubber bullets. The riots resulted in eight deaths, over 900 injuries and 450 arrests.

Eight countries, including the US, UK, Canada, Australia and Singapore, released advisories warning about the potential for further unrest. Meanwhile, Indonesian authorities deployed at least 40,000 soldiers to Jakarta in anticipation of further political protests, which are expected to continue.

Pre-Election Polarisation

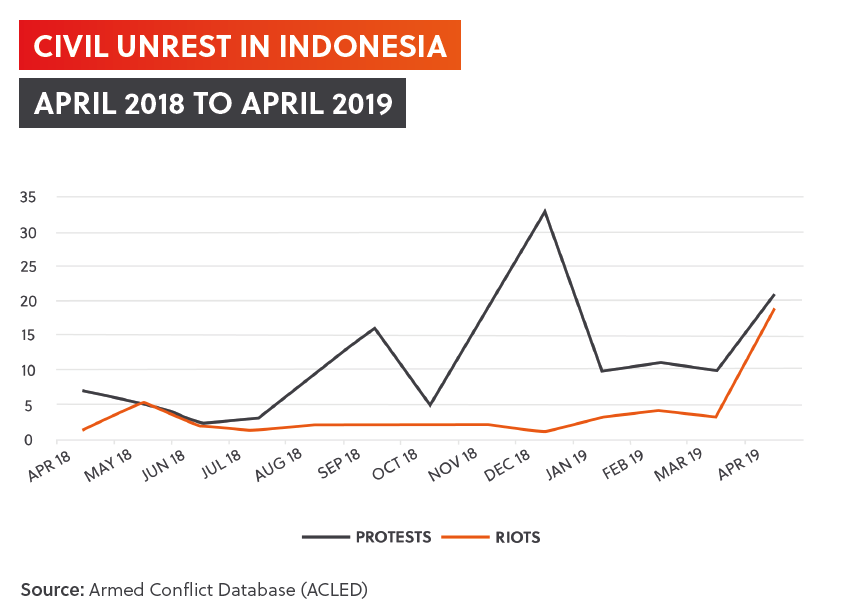

The violence highlights deep societal divisions and political polarisation over issues pertaining to ethnic and religious identity politics. Local media and civil society groups accuse both Prabowo and Jokowi of employing social media “buzzers,” agents pushing political messaging through the spread of hoaxes and fake news online, to rile up their respective bases. For the Prabowo camp, this included a misinformation campaign accusing Jokowi of being anti- Islamic, a communist and a stooge for Chinese economic interests. This polarisation seemingly correlates with an increase in the number of protests and riots over the past year. Notably, while the number of peaceful protests fluctuated depending on the issues of the day, the number of violent riots spiked ahead of the election in April 2019.

Anti-Chinese Sentiment

Xenophobic sentiment towards both Indonesia’s local Chinese minority and foreign Chinese commercial and political interests exacerbates the threat of civil unrest. In the wake of the May 2019 riots, Indonesian authorities suspended access to social media due to a misinformation campaign targeting local and foreign Chinese people and interests

The violence highlights deep societal divisions and political polarisation in the country.

Using photographs of light-skinned security personnel as “proof,” one hoax said Chinese security forces had infiltrated Indonesia disguised as foreign workers employed on Chinese-funded infrastructure development projects, one of Jokowi’s signature policy initiatives. The misinformation campaign added that these alleged “Chinese agents” were responsible for the fatalities during the May 2019 riots, indicating that Chinese development projects will continue to be politicised as the current tensions unfold.

While these claims seem outlandish, many Prabowo supporters have indicated they believe them wholeheartedly. Throughout his political career, Prabowo has tapped into the periodically deadly resentment towards the Chinese-Indonesian minority over perceptions about their relative wealth and suspicions regarding their national loyalty. In the lead up to the election, for example, he formed an alliance with the Front Pembela Islam (Islamic Defenders Front, FPI), the Islamist vigilante group which spearheaded the November 2016 campaign to oust Jakarta’s first ethnically Chinese governor.

Agents Provocateurs?

Compounding the aforementioned threats, Indonesian police claim that Islamist militants and other as yet unidentified interest groups acted as agents provocateurs to incite the crowd to greater violence and potentially radicalise Prabowo’s religious base. The apparent mystery surrounding the riots’ eight fatalities features prominently in these concerns. Four of those killed sustained stab wounds and the remaining four were shot. Police insist that officers did not use live ammunition to disperse protesters which is indeed not in line with the police force’s anti-riot tactics- and allege that Islamist militants were responsible for at least some of the deaths. Two of the rioters detained by police were members of Gerakan Reformis Islam (Islamic Reform Movement, GARIS), a local Islamist civil society group, the leader of which pledged allegiance to Islamic State (IS). The suspects reportedly told investigators that participation in the riots was a way of waging jihad. At least six other suspects were arrested attempting to smuggle weapons, including firearms, into the city ahead of the riots as part of a plot to assassinate senior government officials.

Indonesian police claim that Islamist militants acted as agents provocateurs to incite the crowd to greater violence.

At the time of writing, investigations into the exact nature of Islamist involvement in the riots themselves are ongoing, and it is unclear if the alleged agents provocateurs were acting as part of a broader plot. However, in the days leading up to the riots, Indonesian security forces arrested 31 suspected members of Jemaah Ansharut Daulah (JAD), an IS-aligned group responsible for past attacks on Christians and police officers. JAD militants were allegedly planning to bomb political rallies and demonstrations linked to the election commission’s announcement of the election results.

Regardless of the exact nature of the terrorist threat, post-election Indonesia’s security environment will remain volatile. A combination of political polarisation, toxic identity politics spurred on by long-standing resentment towards the Chinese-Indonesian minority, and potential Islamist violence poses an acute challenge to Jokowi’s second term and will contribute to a worsening of Indonesia’s overall security environment. This includes the potential for further politically motivated protests and violent riots, which will become especially prominent in the coming months as Prabowo’s legal challenge to the election results drags on.