Rajapaksa Returns: Sri Lanka's October 2018 Political Crisis

On 26 October, Sri Lanka’s President, Maithripala Sirisena, suspended parliament and replaced Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe with his old political rival and the country’s former strongman president, Mahinda Rajapaksa. Wickremesinghe resisted the efforts to unseat him and, at the time of writing, has refused to vacate the official prime minister’s residence in Temple Trees, Colombo. Both Wickremesinghe and Sri Lanka’s parliamentary speaker characterise these developments as an undemocratic coup, saying it violates the country’s 2015 constitution, which placed limits on the power of the presidency. The parliamentary speaker further alleges that elevated political tensions could devolve into a “bloodbath.” Given the country’s recent history of violent civil unrest, the speaker’s assessment is worth keeping in mind. With political tensions running high, firms based in, or looking to enter, Sri Lanka are advised to closely monitor these developments in case of an escalation on the ground.

Domestic Drivers of Political Volatility

Relations between President Sirisena and ousted Prime Minister Wickremesinghe deteriorated in recent months. During the January 2015 election, the pair had formed a coalition to defeat former President Mahinda Rajapaksa, whose 2005-2015 tenure was marred by allegations of corruption and human rights abuses. However, relations between the two worsened following the February 2018 local election, in which Rajapaksa’s Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (Sri Lanka People’s Front, SLPP) secured 40 percent of the vote. The deteriorating relationship culminated in Sirisena accusing of Wickremesinghe of conspiring with Indian intelligence services to have him assassinated, prompting him to switch allegiance to Rajapaksa, previously a bitter rival. Both Wickremesinghe and the Indian government have denied these allegations.

Rajapaksa’s sudden elevation to the prime ministership has hastened his re-emergence as a dominant force in Sri Lankan politics. The momentum behind him was already underway before the current crisis, largely spurred on by growing discontent over slow economic growth, ironically hindered by debts accrued under the Rajapaksa administration, and growing Sinhalese Buddhist nationalism. Rajapaksa is seen as a hero among nationalist groups and is largely credited with winning the 1983-2009 Sri Lankan Civil War against ethnic Tamil separatists.

Increased Threat of Civil Unrest

The current political crisis and Rajapaksa’s consequent return to political prominence has already increased the threat of violent civil unrest in Sri Lanka, particularly in the capital, Colombo. Between 26-28 October, Buddhist nationalist protesters loyal to Rajapaksa occupied the offices of several local media companies and forced editors to write up front-page stories announcing Rajapaksa’s elevation to the prime ministership. They also laid siege to the residences and offices of several ministers deemed to be loyal to Wickremesinghe, prompting the bodyguard of the petroleum minister to shoot at protesters, killing one and injuring two more. In turn, tens of thousands of protesters loyal to Wickremesinghe’s United National Party (UNP), as well as civil society groups opposed to the president’s allegedly unconstitutional intervention, protested throughout central Colombo on 30 October. Further protests by both factions are highly likely in the coming weeks as parliament is scheduled to resume its operations on 14 November. There is a degree of uncertainty as to this date, as the scheduled reopening of parliament has already been delayed multiple times since the crisis started. Both sides will attempt to pressure parliamentarians into backing their respective factions and will be eager to demonstrate public support through mass mobilisation of their opposing bases. After November, residual tensions will continue to drive politically motivated unrest in the longer term, especially ahead of the upcoming presidential election, scheduled for an as of yet unconfirmed date in 2019.

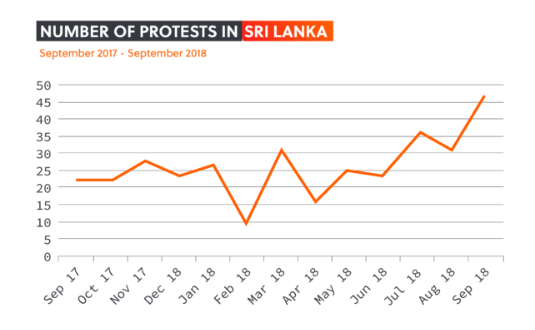

Rajapaksa’s return to power is also expected to further exacerbate Sri Lanka’s existing sectarian and ethnic conflicts, particularly with the country’s ethnic Tamil, due to residual tensions over the civil war, and Muslim minority communities. Incidents of civil unrest are common in Sri Lanka (see Figure 2), and these tensions are likely to further increase the frequency and intensity of future protests. Notably, in March 2018, anti-Muslim sectarian violence by Buddhist nationalist mobs in the central Kandy District prompted Sri Lankan authorities to declare a countrywide state of emergency. At least two people were killed and hundreds of Muslim-owned businesses, residences and mosques were set on fire. Similar incidents are expected as the Buddhist nationalist movement will be empowered should Rajapaksa win the current power struggle, and will likely stage retaliatory riots and attacks should he lose.

With this volatility in mind, foreign firms and personnel based in Sri Lanka should review their crisis management procedures to limit the commercial impact of violent civil unrest, and firms looking to enter the Sri Lankan market should conduct thorough threat assessments prior to entry.

Achieving Resilience Amid Political Instability

By Peter Dolamore, Director, Head of Crisis Preparation, S-RM

When political instability occurs, it places the business leader in an invidious position. You are concerned foremost for the safety and well-being of your people, but also for the preservation of your operations and assets.

Judgement is key in these situations, but your usual ability to make good decisions is impeded by a mire of complexities and heuristics. Your own optimism bias is probably one; perfectly understandable, given your wish to be positive for the people around you. Differing perspective is another. To your colleagues on the ground, who are familiar with the environment, this might be just another day. Your senior management sitting back in Head Office, whose understanding is fuelled by news headlines and social media, might not be so sanguine. You do not want to risk everything by shutting up shop and leaving, but neither do you want to be the proverbial slowly-boiling frog.

S-RM has accumulated know-how on your behalf, after years of supporting clients, both in frontier markets and in those moments when previously reliable commercial environments are suddenly turned on their heads. Our range of services are specifically designed around building resilience into your business, project or operation to ensure they can weather the difficulties that sudden instability can bring. Prevention is always better than cure and Preparation is a close second – but S-RM knows that crises are, by their nature, simply unforeseen. That’s why our Response service is ready to provide close support to organisations in their hour of need – wherever and whenever that is.