Opening up the UAE to foreign ownership: What next for free zones?

Last month, UAE’s Prime Minister Sheikh Mohamed bin Rashid Al Maktoum confirmed that a new investment law, which is to allow foreigners to own up to 100 percent of companies in the UAE, will come into force by the end of 2018. The highly anticipated law comes alongside other reforms that aim to make the UAE’s investment environment more open to foreign finance and further reduce the economy’s reliance on oil; the UAE Ministry of Economy is aiming to increase the non-oil sectors’ share of GNP from 70 to 80 percent by 2021. Other measures include a new 10-year residency visa which will be offered to foreign nationals working in scientific and medical industries – previously visas were valid for just two or three years. Additionally, new bankruptcy laws introduced in 2016 now allowing struggling companies to restructure their debts.

The UAE federal government has warmed to the idea of relaxing foreign ownership restrictions since it sold up to 20 percent of State-owned telecoms operator Etisalat to foreign investors in 2015. Etisalat’s share price subsequently rose by over a third in just six months.

The UAE is also keen to remain the Gulf’s main investment hub as its neighbours in the Gulf step up efforts to woo foreign capital as part of a region-wide strategy to diversify away from oil. Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and Kuwait have all loosened corporate governance laws in recent years in an attempt to attract international capital.

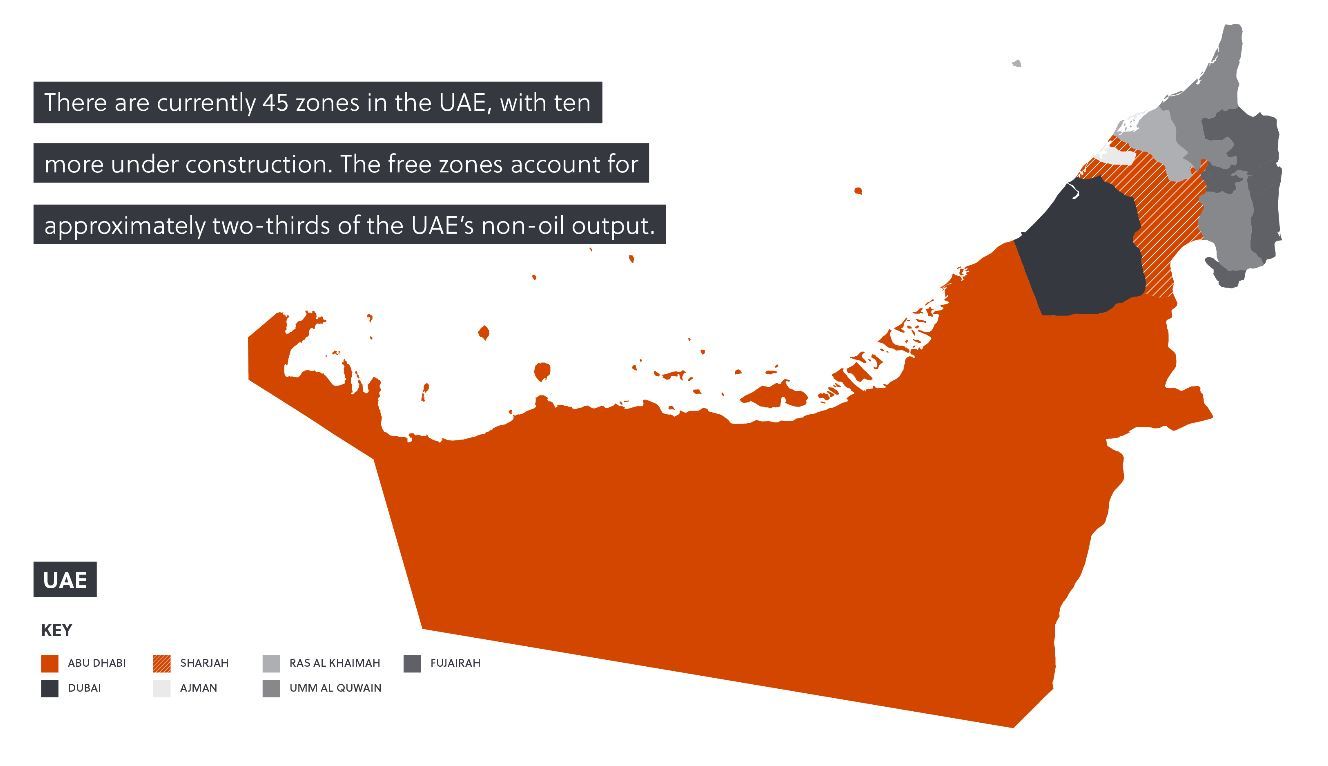

The new investment law calls into question the role of free zones in the UAE. Free zones, typically either based around major transport infrastructure or focused on a specific industry, are free from national regulations and until now have represented the key entry point for foreign investment into the UAE. There are currently 45 zones in the UAE, with ten more under construction. The free zones account for approximately two-thirds of the UAE’s non-oil output.

There is a debate over how much the new investment law will disrupt free zones. If 100 percent foreign ownership is implemented fully in the UAE’s mainland, free zones will have to rely on other advantages. They will continue to rely on financial sweeteners such as waiving corporation and income taxes or allow for the full repatriation of profits. But this alone may not deter investors wanting to set up in the mainland and develop their businesses there; lucrative government tenders are generally out of reach for free zone companies, except in Abu Dhabi.

The more established free zones boast superior physical and legal infrastructure and have reached critical mass. The UAE’s oldest free zone, the Jebel Ali Port and Free Zone speedily connects its occupants to the largest port in the Arab region and the Al Maktoum International airport, whose current USD 36 billion development is to make it the largest airport in the world. It is home to 7,000 businesses and 150,000 workers.

Likewise, the Dubai International Financial Centre, home to 17 of the world’s 25 largest banks, has brought its financial regulations in line with international norms. These are enforced by independent DIFC courts, nominally insulated from the political tendencies of the national government.

Less established free zones may be more vulnerable. In particular sectors such as healthcare, retail and education, in which companies need local branches to access their consumer base in the mainland, would be most likely to move away from free zones. Which sectors will be exposed to the new investment law has yet to be disclosed. The government has hinted that the tourism, real estate, manufacturing, education and financial sectors will be included.

Free zone authorities should also look at the size of the businesses they wish to retain. Free zones’ cheap access to energy and simplified administrative procedures may be most appealing to start-ups and SMEs, whereas the opportunity to conduct business in mainland UAE will perhaps favour large multinationals as well as firms involved in industries like healthcare, which receive high-value government tenders that are only available to mainland UAE.

There are still many opportunities for free zones to adjust to the new investment conditions. Uncertainty remains over elements of the new law; for example, foreign investors may have to meet certain capital requirements to keep their 100 percent stakes on the mainland. The actual timeline for implementing the new law is similarly unclear. These factors provide free zone authorities with a window to bolster their offerings with increasingly business-friendly regulations or improved infrastructure.