On the rise? The role of crime in Libya's political crisis

There is growing optimism among international and domestic stakeholders that Libya is reaching a resolution to the conflict between the Government of National Accord (GNA) and the self-declared Libyan National Army (LNA). Yet, a decade of political instability since the October 2011 ousting of Muammar Ghaddafi has brought with it a complex security environment characterised by criminal networks that operate freely. Increasingly challenging is the fact that the true nature of crime in Libya remains obscured by official government statistics severely impacted by underreporting and the overlap of conflict and crime-related violence.

UNDERREPORTING

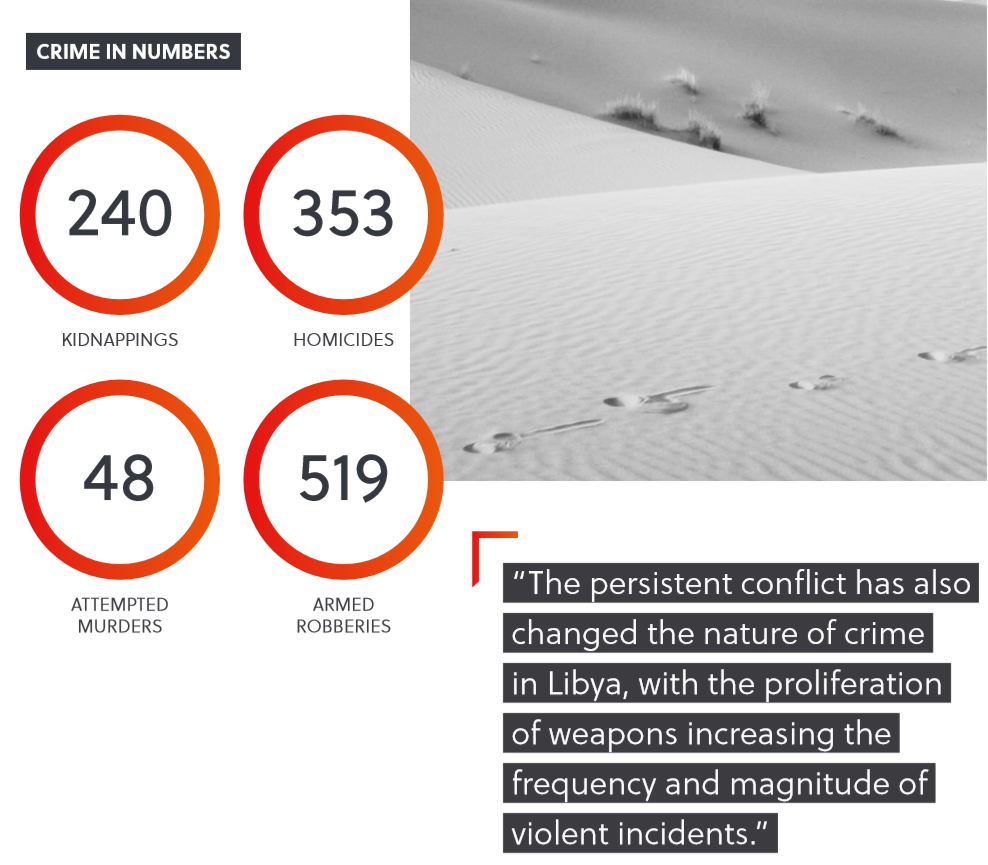

In January this year, the GNA released its national crime statistics for 2020. According to the UN-backed body, 353 homicides, 519 armed robberies and 240 kidnappings were recorded nationally. The homicide figures translate into a homicide rate of 5.2 homicides per 100,000 people. While the GNA was clear to paint this as a high incidence of crime in the country, these figures are a far cry from known global crime hotspots like South Africa (36 homicides per 100,000 people), placing Libya alongside countries such as Zambia and Argentina at 5.0 homicides per 100,000 people. And, while this could translate into a perception of moderate crime levels in the country relative to the global stage, a more likely reality is that this brings into question the veracity of these figures.

Since the LNA’s April 2019 offensive on Tripoli, at the time controlled by the GNA, Libya has been on the brink of a new civil war. While the LNA, backed by Egypt, Russia, and the UAE, initially gained considerably territory in western Libya, Turkish military support for the GNA allowed it to push back against the offensive. By June 2020, the LNA lost almost all the territory it captured since April 2019 and by October the two sides had agreed to a ceasefire. While the increased political will for peace remains high, the need to prioritise, at first a military advance, and subsequently, peace and political stability, has meant state responsibilities have been disrupted or delayed. Accordingly, there is no official or independent inventory regarding indicators of crime in Libya. While the GNA has released occasional figures for the areas under its control in western Libya and has warned of high crime rates, authorities aligned with LNA in the east claim that security services here are working effectively, and that while crime occurs, it is at a lower rate. These divergent narratives add to the lack of clarity over the state of crime in the country. Meanwhile, proxy measures, such as the ENACT Organised Crime Index for Africa 1, rank Libya as among the highest scoring countries in Africa regarding criminality, with Libya ranked 7 out of 54 on the index.

CONFLICT AND CRIME RELATED VIOLENCE

Understandably, protracted conflict in Libya since 2011 has contributed not only to a precarious security situation but an environment easily exploited by criminal actors. This has most prominently translated into a higher incidence of organised crime activity and associated violence. There are numerous entrenched criminal markets in Libya, including human trafficking and human smuggling, as well as arms and narcotics trafficking. Furthermore, Libya has a diverse array of mafia-style militia groups operating in the country, controlling territory and who are heavily involved in the many criminal markets making organised crime pervasive.

Dr. Jazia Shaiter, a professor of criminal law at the University of Benghazi, claims the persistent conflict has also changed the nature of crime in Libya, with the proliferation of weapons increasing the frequency and magnitude of violent incidents. According to Shaiter, “weapons are in every house and every car, and consequently the type of crimes has changed. Thefts have become armed robbery, and quarrels have come to end with murder or attempted murder.”

Since 2011, there have been an estimated 21,200 conflict related deaths, 4,700 of which include civilian deaths from direct targeting. However, given the increased intersection between conflict and crime in a security environment that includes some 280 armed groups, it is highly likely that figures detailing conflict-related fatalities also include criminally-motivated deaths. And, while law enforcement in Libya, which has largely been outsourced to various militias, is moderately effective in certain areas, the overwhelming majority of the institutional and regulatory frameworks required to effectively tackle the threat of organised and violent crime remains ineffective.

SYSTEMIC INSECURITY

Many are hopeful that the October 2020 ceasefire between the LNA and GNA and ensuing appointment of an interim government in January 2021 will pave the way to peace in Libya. However, as the newly established interim government seeks to organised parliamentary elections in Libya by December 2021, the new government body and incoming administration will inherit a highly fractured security environment characterised by entrenched criminal activity and transient militant and criminal groups. In the absence of a clear picture of the state of crime within the country, it will take time to understand and then effectively address this systemic insecurity. The path to peace will be a bumpy one and threats such as organised and violent crime will remain key challenges in a new Libya.