Disappearing act: Virtual kidnappings in North America

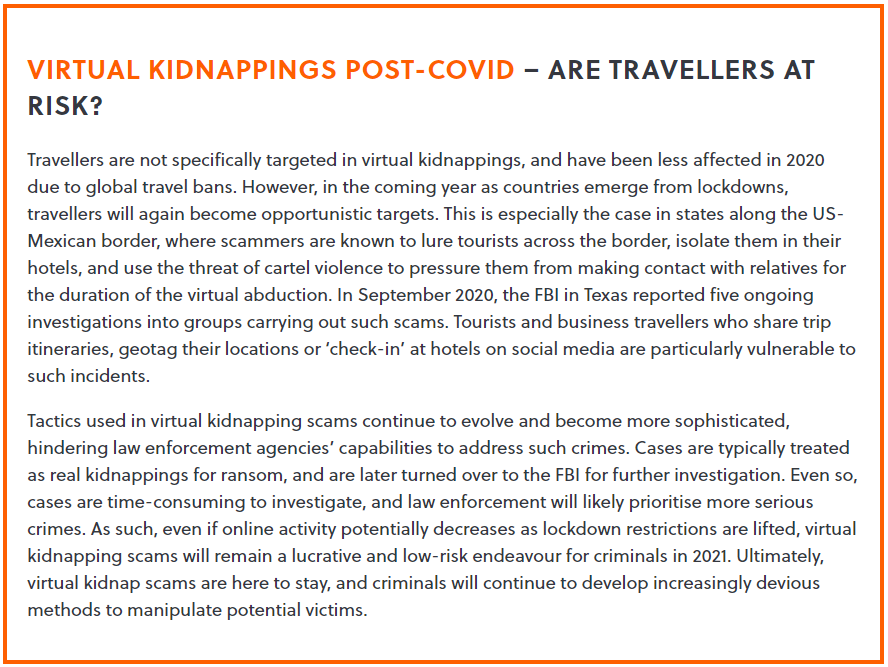

Virtual kidnappings – in which the perpetrator convinces family members that a loved one has been taken, and then extorts a ransom demand – have increased globally in the past few years, although cases in North America remain comparatively rare. However, in 2020, both the FBI and police in some areas warned the public that reports of fake abductions have increased. These law enforcement warnings reflect a growing concern that the pandemic may have created a permissive environment for criminals to carry out more virtual kidnappings. While local nationals and resident foreign nationals have been the main victims, such incidents could also pose a threat to travellers as cities begin to encourage tourism to bolster their economies following lockdowns.

WHO IS TARGETED?

Criminals commonly target locals. Victims are usually elderly people who may be more vulnerable to online scams, parents of missing children, or individuals with relatives who live in other states or countries, and who cannot easily be reached. In such scams, criminals use personal information gleaned from the victim’s social media profiles to tailor their attack. For example, in Washington, police reported a virtual kidnap scam in which criminals search social media sites for people who have reported missing children or other relatives. They then target these individuals by claiming to have taken the missing person, and demand ransoms in the form of wire transfers and gift cards. In one case, scammers had obtained court documents submitted by parents of a missing teenager in the Spokane area in January. Using a burner phone, they demanded an unspecified ransom from the family for their son’s release. Following a police search, the teen was later found unharmed.

COMMON TACTICS USED IN VIRTUAL KIDNAPPINGS

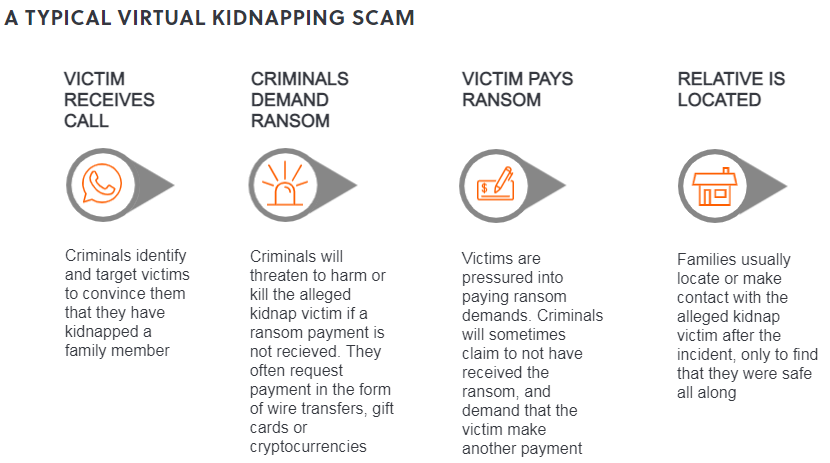

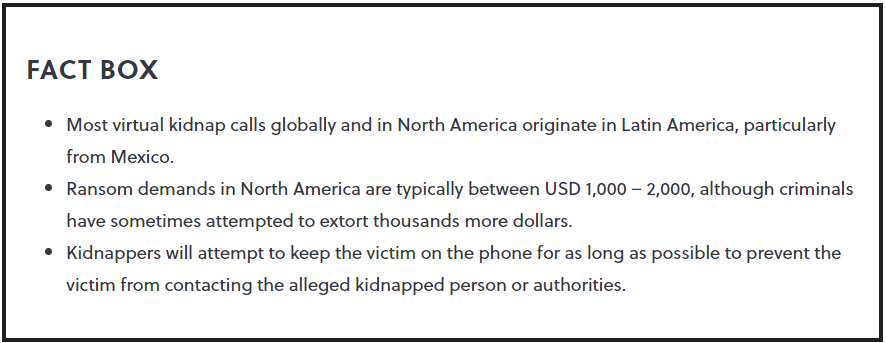

Some virtual kidnappings are carried out indiscriminately, and commonly involve gang members in Latin American prisons cold-calling hundreds of local US numbers to increase their chances for success. According to David Lawson, Deputy Head of S-RM’s Crisis Response team, such calls follow a similar pattern globally, with callers convincing people that they have kidnapped their relatives, and pressuring them to stay on the line while they make quick electronic transfers to the alleged kidnapper’s account. The perpetrators keep the victim on the line for as long as possible to instil a sense of panic and to prevent them from contacting authorities. Lawson says that a it is critical for the kidnapper to illicit a “swift, ‘unthinking’ and emotional response from the target.” In October Oregon police reported such a generic virtual kidnap scam in the Salem area in Massachusetts, where multiple victims reported that they had received calls demanding a ransom to release a kidnapped family member. The callers pressured the victims to remain on the phone while they withdrew and wired the ransom money to Mexico. Victims reported hearing screams in the background, which were likely pre-recorded.

Occasionally, criminals stage targeted two-way virtual abductions, in which both the alleged kidnap victim and their relatives are extorted. Perpetrators obtain personal information from the first victim, and use it to target their relatives. In April and May, Canadian police warned of virtual kidnap scam targeting the Chinese community on Vancouver Island. In one case, a woman was contacted by a Mandarin-speaking individual claiming to be with the Chinese police. The perpetrator convinced her to send money and personal information to secure the safety of her family in China. The scammer then used the information to convince her family that she had been kidnapped, and attempted to extort a ransom demand.

KIDNAP IN A TIME OF COVID

Although the FBI and Canadian police claimed that reports of virtual kidnappings increased in 2020, they have also admitted that such incidents are significantly underreported. If the extortion attempt fails, or when the supposed kidnapped individual is discovered to be safe, victims of the scam often do not report the incident, particularly if the ransom demand was small.

There is no clear evidence to suggest that virtual kidnappings have increased as a result of the pandemic and its associated lockdown measures. However, the lockdown period likely created permissive conditions in which criminals could target potential victims. As more people began to spend time online due to social distancing practices, this exposure would have increased opportunities for criminals to target a more engaged and available online audience – criminals particularly targeted social media users.

US law enforcement officials have reported that some US-based street gangs have recently begun to stage virtual kidnappings by masquerading as Mexican cartels to increase the credibility of their threat. This indicates that petty criminals and smaller gangs in the US have sought to diversify their operations during lockdown, as restrictions on movement may have decreased their profit typically obtained from drug trafficking and other forms of racketeering. It is feasible that they will continue to stage such scams in the coming year to make up for any financial losses.

LIMITED THREAT OF VIOLENCE

By their nature virtual kidnappings are not typically violent. Although criminals rely on the threat of violence to pressure victims into paying ransom demands, or not contacting family members, no reported incidents of virtual kidnappings in North America in the past few years have involved physical harm to the victims. The alleged abductee and the targeted persons usually do not come into physical contact with the criminals orchestrating the fake abduction, as perpetrators are usually far away from where the scam takes place.