Companies vs. Communities: Indigenous Activism Around the World

Indigenous people argue that such operations have negatively affected their way of life; as pollutants and chemical spills seep into the land and water, health concerns emerge due to drinking water and soil pollution, and sustainable fishing and subsistence agriculture becomes increasingly untenable. Another grievance centres on land rights, as indigenous groups have accused governments of granting drilling and mining concessions without consulting communities who inhabit the area. These concerns are exacerbated by the effects of climate change, which continue to reduce arable land and natural resource supplies.

In 2019, amid global protests denouncing climate change and environmental exploitation, indigenous communities’ opposition to extractive operations have manifested in various ways. Their methods have ranged from legal action and peaceful protests to more aggressive tactics, aimed at forcing companies to suspend operations – or even close project sites entirely – in order to preserve vital resources. These actions often have an adverse commercial impact on the affected companies, and in some cases, presents a safety threat to staff. Such opposition will likely continue in the coming years, as worsening environmental conditions and commercial projects continue to complicate their way of life.

Indigenous opposition to extractive sector operations will likely continue in the coming years, as worsening environmental conditions and commercial projects continue to complicate their way of life.

PEACEFUL PROTESTS

Indigenous opposition to mining or oil drilling operations most frequently takes the form of peaceful protests – a trend which continued in 2019. Groups such as the Xolobeni community, who protest titanium mining in South Africa’s Eastern Cape Province, or the Xinka people who denounce silver mining in southern Guatemala, continued to hold peaceful protests in recent years, aimed at raising awareness of their grievances with minimal disruptions to commercial activities. However, protests can occasionally attract significant attention from the media, activists and other civil society groups, increasing pressure on governments to prevent or limit drilling or mining operations. Peaceful protests by the Didipio community in Nueva Vizcaya, Philippines, led to global rallies in October 2019, calling for the non-renewal of a gold mining company’s contract in the area.

Even in the case of peaceful protests, incidents of civil unrest that have obstructed extractive operations have often drawn a robust – and sometimes violent – security response, with security personnel employing teargas, water cannons and occasional live ammunition to disperse protesters. In 2019, such crackdowns have continued, as states have sought to allay investor fears amid growing climate activism worldwide. Yet, such crackdowns increase the threat of clashes between protesters and security personnel, which can further anger demonstrators, adding to their list of grievances and prolonging protests.

SABOTAGE

In recent years, indigenous protesters have occasionally engaged in acts of sabotage, damaging machinery and infrastructure in an effort to force disruptions to extractive activities. Sabotage tactics most commonly affect oil pipelines, which are often more exposed and less secure than oil drilling facilities. Such exposure enabled members of the Yoemi group, of the Yaqui community in Loma de Bacum, Dakota, to destroy an 8-meter section of a USD 400 million natural gas pipeline forming part of the contentious Dakota Access pipeline in August 2017.

BLOCKADES

Indigenous groups often erect barricades or block the entrance of the targeted facility with the aim of frustrating staff access, or stopping vehicles transporting materials and equipment. In October 2019, indigenous communities from the Chilean Atacama salt flats blocked access to lithium mines operated by the world’s top-two lithium producers, reportedly forcing the mines to suspend operations.

Such protests can last several days to several weeks. In 2016, residents of the Peruvian Amazon basin launched a flotilla which blocked oil transportation on the Lot 8 oil field located on the Marañón River for four months. Similar sustained demonstrations took place between September and November 2017, when indigenous activists peacefully blockaded 50 oil wells at Lot 192, Peru’s largest oil concession. The overall production loss across the lot amounted to a reported 12,000 barrels per day for the duration of the blockade. As such, blockades can significantly delay commercial operations while indigenous representatives negotiate a solution with the company and the government.

OCCASIONALLY AGGRESSIVE MEASURES

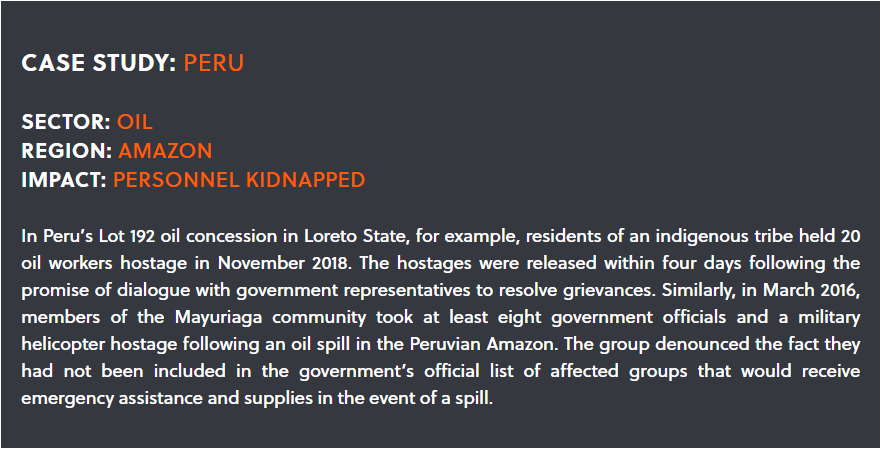

In isolated cases – mainly in South America, and occasionally in Sub-Saharan Africa – indigenous communities affected by ongoing extractive activities in the Amazon region have engaged in aggressive measures. Tactics in the past few years – including isolated occasions in 2019 – have sometimes included holding government officials and extractive workers hostage until their grievances are addressed. Such measures will likely become more attractive if indigenous communities’ grievances remain unaddressed amid the ongoing effects of climate change.

A PERSISTENT IMPASSE

As global efforts to counter the environmental impact of extractive activities grow due to concerns over climate change, clashes of interest between mining companies and indigenous groups will likely persist in the coming months. Indigenous activism – exacerbated by worsening environmental conditions, and emboldened by support for indigenous communities – will continue to drive potentially disruptive acts of civil unrest against oil and mining operations, with Latin America likely to remain the most affected region.

Read our 2020 Political Violence Special Edition for more global security insights.