Breaching the Defences: Europe Rocked by Danske Bank's EUR 200 Billion Money Laundering Scandal

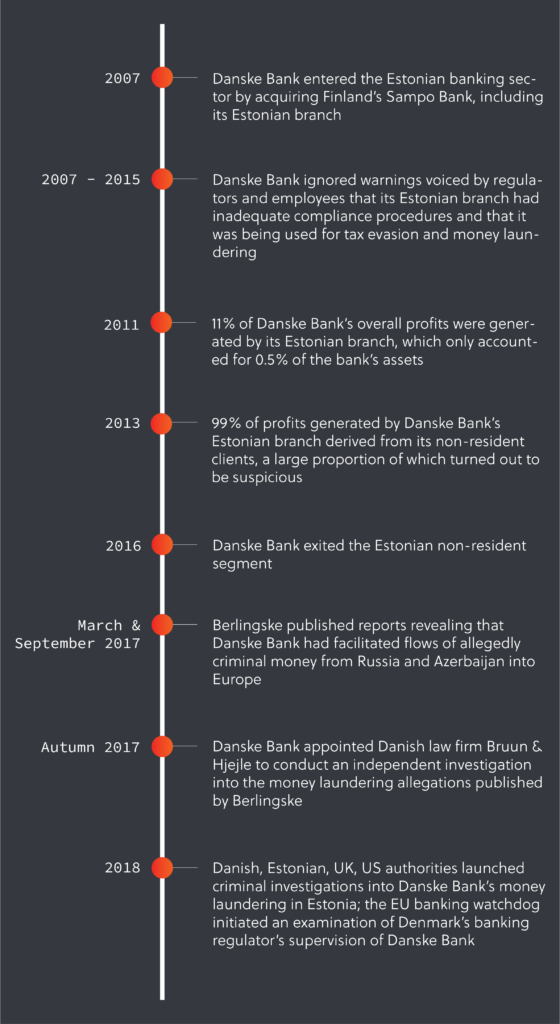

Since March 2017, Denmark’s Danske Bank has been embroiled in scandal over its reported failures to prevent money laundering at its Estonian branch between 2007 and 2015. Allegations made by Danish daily Berlingske, as part of a wider body of international media reporting into money laundering by European banks, have culminated in criminal inquiries into Danske Bank led by Danish, Estonian, UK, and US authorities. The case may do irreversible damage to Danske Bank’s reputation, despite the relative insignificance of its Estonian branch to the bank as a whole – as at 2011, the branch accounted for only 0.5% of Danske Bank’s assets.

The case against Danske Bank centres on allegations that the bank facilitated the flow of €200 billion of non-resident money through its Estonian arm. The majority of these funds are suspected to have been the proceeds of criminal activity and tax evasion committed in the former Soviet Union, most prominently Russia and Azerbaijan. Danske Bank’s Estonian branch is accused of failing to identify these suspicious flows despite signs of illegal activity.

In the wake of these criminal investigations, Danske Bank’s CEO Thomas Borgen resigned in September 2018. Chairman Ole Andersen has since also announced his intention to resign. The bank’s share price also dropped 6 percent in September 2018 alone and it is likely to face fines in the billions of US dollars.

While media reports generally hold the Estonian branch’s management responsible for these lapses, investigations launched by EU and US authorities have suggested that the reality is more complex. Evidence increasingly indicates that while Danske Bank’s central management failed in its duty to prevent money laundering, Estonian and Danish financial regulators could have intervened sooner and much more forcefully.

A DEFECTIVE BALTIC BANKING SECTOR

Since the mid-2000s, Estonia and the other Baltic States have positioned themselves as a private banking centre, effectively serving as a go-between for money from the former Soviet Union seeking to head West. Their offering has, however, differed from that of the traditional private banking sector through its greater focus on expediting transactions, often at the expense of KYC procedures.

One of the most infamous examples of the Baltic banking sector acting as a financial ‘Wild West’ to the benefit of money launderers is the so-called ‘Russian Laundromat’, a money laundering scheme through which an estimated $20 billion to $80 billion was moved from Russia to Europe between 2010 and 2014. Investigations into the Laundromat pointed the finger at a number of financial institutions, most notably the use of Latvia’s Trasta Komercbanka in the large-scale laundering of Russian money, and the lack of scrutiny they applied to the source of capital flows.

In a similar fashion, Danske Bank’s Estonian branch has been accused of facilitating large-scale money laundering activities. An independent investigation commissioned by Danske Bank, which was carried out by Danish law firm Bruun & Hjejle after the publication of Berlingske’s findings, determined that “branch management was more concerned with procedures than with identifying actual risk”.

Yet the Estonian branch’s management did not only deliberately fail to identify risky customers; it actively encouraged them. 50 current and former employees of Danske Bank’s Estonian branch are suspected of having colluded with clients to circumvent AML requirements, and 26 employees, including the branch’s CEO, are under investigation by the Estonian authorities for facilitating the laundering of alleged proceeds of crime originating in Russia.

A FAILURE OF INTEGRATION

It is a little too simplistic, though, to leave the blame there. Although the Bruun & Hjejle report cleared Danske Bank’s management of legal wrongdoing, there are suggestions that it was ultimately the Danish bank’s failure to integrate its Estonian branch fully that precipitated the alleged money laundering activities.

Danske Bank has been accused of doing little to ensure staff at its newly acquired Estonian branch adopted its culture and, especially, its attitude to AML. The bank’s Estonian branch mainly maintained KYC documents in Estonian or Russian, and Danske Bank, instead of insisting that these documents be translated into Danish or English to increase its oversight of the branch, simply assumed that its Estonian branch was following appropriate AML procedures.

Further, in 2008, Danske Bank took active steps towards limiting its oversight of its Estonian branch by deciding against extending the use of its more rigorous compliance software to the branch. Given its failure to fully integrate a newly acquired branch, exacerbated by the fact that for most of 2013 it did not even have a specifically-appointed central AML officer, Danske Bank’s head office has a lot to answer for.

A FAILURE OF REGULATION

Estonian and Danish financial regulators also need to shoulder significant responsibility for Danske Bank’s current plight. In the first instance, Estonia’s financial regulator criticised Danske Bank for inadequate compliance processes in Estonia in 2007, but failed to insist on improvements to the branch’s processes.

In 2012, the Danish regulator limited its follow-up to AML complaints voiced by its Estonian counterpart to a mere request for information from Danske Bank. Even after the Berlingske investigations were published and the regulator reprimanded Danske Bank for its inadequate compliance procedures in May 2018, no meaningful action was taken. The Danish regulator’s inaction, even after allegations of Danske Bank’s facilitation of money laundering gained media prominence, suggests an institutional absence of will, which could explain why it failed to act on earlier warnings voiced by regulators and whistle-blowers.

REGULATORS OF THE WORLD, UNITE

Prosecutors in several countries have filled the vacuum left by the Estonian and Danish banking regulators by conducting their own criminal investigations. Since 2018 Estonian and Danish prosecutors have launched criminal investigations, swiftly followed by the US Department of Justice and the UK’s National Crime Agency, with the latter examining British shell companies that banked with Danske Bank’s Estonian branch. The EU, meanwhile, has begun examining Denmark’s banking regulator for its poor supervision of Danske Bank.

This all casts the Estonian and Danish national regulators in a poor light. Opportunities were certainly missed by both regulators to insist on improvements to Danske Bank’s compliance procedures, though it is of course impossible to know whether these measures would actually have prevented any impropriety at the bank. Either way, Danske Bank appears set to bear the consequences of its actions, most notably in the form of a hefty fine from the US Department of Justice, estimated to be anywhere between $2.3 billion and $8.3 billion. The outcome of the EU investigation for Denmark’s banking regulator, meanwhile, remains unclear.

Responsibility for combatting money laundering is not limited to individual banks or even individual branches, with national banking regulators also having a duty to be proactive in their supervision of banks and to provide AML guidance. The Danske Bank scandal will go down in history as one of the largest examples of its kind – the scale of the money laundering which is reported to have taken place over 8 years is truly enormous. However, if there is one lesson to take from this case it is perhaps that preventing money laundering requires a number of parties to work closely and diligently with one another, and that European defences against such malfeasance are only as strong as their weakest link.