An Old Agenda Renewed: Boko Haram's Territorial Ambitions in Nigeria

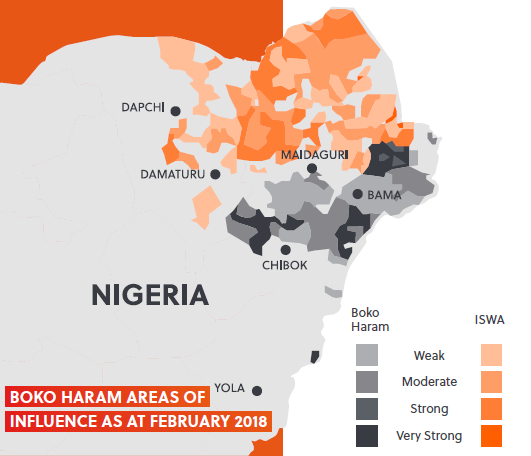

On 7 September, suspected Boko Haram militants briefly captured the town of Gidimbali, Borno State, in one of the first displays of a successful territorial gain in over two years. The group was able to hold onto the town for several hours before being pushed out by Nigerian military forces. The Islamic State-backed faction of the group, led by, Abu Mus’ab Al Barnawi and commonly referred to as Islamic State’s West African Province (ISWAP), has since claimed responsibility for the attack. Despite being successfully repelled, the incident, coupled with growing fatigue and frustration among Nigeria’s security forces, has raised concerns that the group could be positioning itself for a resurgence, again aimed at seizing territorial control in northeastern Nigeria.

Boko Haram has previously displayed the intent and capability to seize control of large areas of territory in Nigeria’s north. Between 2014 and 2015, at the height of its insurgency, Boko Haram reportedly maintained control, or at least strong influence, over 30,000 km2 of land. The group was subsequently pushed out of its territorial strongholds by the Nigerian military, together with the support of the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF), a combined multinational formation comprising military units from Benin, Cameroon, Chad, Niger, and Nigeria. Following this territorial defeat, Boko Haram was quick to adapt its strategy, by embarking on a violent guerrilla campaign characterised by a marked increase in the use of suicide bombings. Yet, this campaign of increasingly indiscriminate violence found little favour with the group’s subsequent backer, the Islamic State (IS), who pushed back on the targeting of Muslim communities in Nigeria. This change in campaign also occurred at a time of increasing rifts concerning ideology and tactics within the group. In an apparent reprisal, in August 2016, IS sought to replace then-Boko Haram leader, Abubakar Shekau, with Al Barnawi, catalysing the ultimate split of the group. Although Shekau has continued to lead his faction in a guerrilla campaign attacking soft targets in Nigeria, Al Barnawi’s ISWAP appears to have gained new momentum this year in its fight against the Nigerian military

ISWAP continues to prioritise military targets in its campaign, and its latest operations in Gidimbali and Bama demonstrate the intent to engage militarily with Nigerian forces and to secure territorial gains. According to local reports, during the 7 September Gidimbali attack, the group employed more sophisticated weaponry, including the use of rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs) and anti-aircraft guns. ISWAP is also believed to be responsible for the July attack against Bama in which the Nigerian military lost 13 vehicles to ISWAP forces, and the subsequent attack on a military base in Jili, near the Chadian border, among several other attacks on strategic military bases. Greater territorial control on the part of ISWAP will benefit its more conventional, military engagement, and such a strategy is likely to encourage further attempts to secure terrain by ISWAP fighters.

Furthermore, ISWAP’s efforts to distinguish itself from Shekau’s faction, often referred to as Jama’atu Ahlissunnah Lidda’awati Wal Jihad (JAS), have also had some success in winning a degree of support within communities. Local media reports indicate that the group has sought to punish fighters responsible for crimes against local communities as well as engage in community projects such as well-digging, to bolster trust among local community members. It is also in the group’s interest to maintain control over these communities to facilitate its taxation networks, while simultaneously gaining access to key commodities like fish and peppers in the Lake Chad Basin. This agenda will further encourage the group’s territorial campaign.

Despite this demonstrated intent to increase the group’s territorial control, the absence of significant gains in this regard demonstrates that ISWAP still has only limited capabilities to achieve this. However, the group is now facing an increasingly fatigued and underresourced Nigerian military, which could pave the way for new opportunities to seize towns. Already, soldiers deployed to combat Boko Haram protested outside Maiduguri Airport, Borno State, in August this year, against unpaid wages and the potential for redeployment to the conflict. Furthermore, as Nigeria enters an election year in 2019, and insecurity burgeons elsewhere, including the growing rifts in the Middle Belt, security forces will become increasingly stretched.

Overall, ISWAP is well positioned to leverage these pending security weaknesses, and it already appears to be testing the waters. In this regard, Boko Haram is far from being “technically defeated” as the Nigerian government is keen to convey. Rather, both factions of the militant group will remain at the forefront of insecurity in Nigeria’s northeast, a vulnerability Nigeria can ill afford ahead of the February 2019 vote. Although a territorial campaign is not new for Boko Haram, the counterinsurgency force combating the group now faces two emerging and divergent campaigns: on the one hand territorial and, on the other, a guerrilla force engaged in indiscriminate violence. This is likely to elevate the complexity of the insurgency in northern Nigeria, and increase the challenges of resolving it.