Agroterrorism

The deliberate targeting of agricultural land as a means of attacking a perceived enemy is not new. Thescorched earth tactics of WWII and the Vietnam War left large swathes of agricultural land devastated. More recently, Islamic State have been lighting crop fires in Iraq since 2019, resulting in food shortages, as well as demanding extra resources to enable more effective guarding of crops. Such attacks can have drastic effects on food supplies, causing widespread destruction of crops and famine. However, in most cases, the lasting effects of fire are limited; depletion in nitrogen levels may reduce fertility for a number of years but, in most cases, replanting can occur the following growth cycle. The significance of a CBRN attack on agricultural land could be both more widespread as well as more enduring, with reduced soil fertility for years after exposure and poisonous toxins contaminating the land for decades.

As far back as 2002, the United States has been investigating the risk to its food supply from agroterrorism. A report by the Council of State Governments noted that, based on the relative ease of conducting such an attack, it raised the question as to why no large-scale attack had yet been perpetrated.

CBRN VULNERABILITIES IN AGRICULTURE

The most significant vulnerability faced by the agricultural sector is its status as a soft target with a large footprint. In the case of traditional terrorism, targets such as nuclear power stations, military sites and government buildings are usually concentrated in a relatively small area where security measures can be put in place to monitor and prevent threats. Agricultural land, by its nature, covers large areas of land (over 350,000 acres in the US Midwest alone) making it impractical to deploy similar security measures. But it’s not only agricultural land that’s at risk; livestock presents a similarly vulnerable target. Overuse of antibiotics, sterilization programmes and dehorning have all contributed to the increased vulnerability of livestock to disease. The movement toward larger herds and breeding operations largely precludes the option of attending to animals individually, making it more likely that emerging diseases will be overlooked.

Given the relative ease with which a perpetrator could commit a CBRN attack against agricultural land or livestock, it is likely that the predominant reason why a significant one has not occurred is its attractiveness as a target. As terrorist attacks traditionally aim to cause mass human casualties and have a particular shock factor about them, agricultural damage doesn’t present the same opportunities as an attack on say a busy shopping centre or sports stadium. However, it may present a viable secondary target for an attack.

WHAT WOULD AN ATTACK LOOK LIKE?

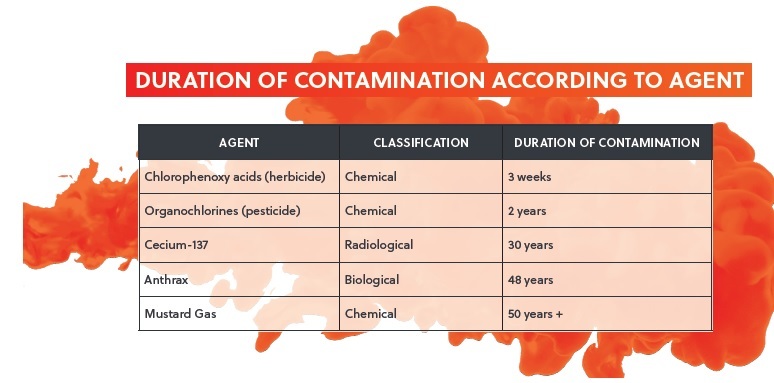

Chemicals have been used on agricultural land for thousands of years. Most are designed to protect crops from pests and keep agricultural land free of weeds. However, their lasting effects on both soil quality and food contamination are a source of contention. This is particularly concerning when considering the potential effects of a chemical agent, such as mustard gas. While the longevity of chemicals in agricultural land is dependent on various environmental factors, mustard gas can to persist in land for up to 50 years. The chemical significantly reduces soil fertility but, being freely soluble, is also absorbed by any food grown on contaminated land preventing its use for crop production.

The most likely method of a deliberate chemical attack would be via aerial distribution – a method traditionally used for disseminating pesticides. This method was used by US forces during the Vietnam War to spray the chemical, Agent Orange, over land in Vietnam. In addition to causing long-term contamination issues, the chemical also resulted in millions of deaths, illnesses and birth defects amongst the Vietnamese population. More recently, there have been allegations by Palestinians against Israel, whom they accuse of having sprayed herbicides from the air to deliberately damage Palestinian crops. These accusations have been attested by the Red Cross.

Radionuclides persist in soil until they decay; for some isotopes this can be decades. Over 30 years after the nuclear disaster at Chernobyl, particles of caesium, strontium, even some plutonium are still found in the soil around the site, making the land too dangerous to farm. The effects of radiation when ingested can cause birth defects and cancer. The Exclusion Zone put in place to contain the effects of the radiation was 2,600 km².

The most likely form of a radiation-based attack on agriculture would be through the use of a dirty bomb – a conventional explosive used to spread radioactive material. Whilst the severity and spread of contamination of a dirty bomb would be much less than that of a nuclear explosion, the enduring impact the attack would have on agricultural land makes it a credible threat.

A biological agent could be introduced into a livestock population with relative ease given the lack of effective preventive measures and the nature of the industry. For instance, livestock are frequently concentrated in confined locations and transported or commingled with other herds, making transmission quick and widespread. The threat posed by biological agents is increased because the livestock won’t show symptoms immediately, meaning they will infect other animals before the disease has been detected. Naturally occurring outbreaks, such as Foot and Mouth (FMD) in the UK in 2001 saw the destruction of 6.1 million animals at a cost of over GBP 3.1 billion. Such instances tend to follow a predictable pattern in terms of consistency with previous occurrences. However, an intentional introduction of a pathogen could differ in that agroterrorists have the potential to release pathogens in several locations in an attempt to initiate multiple simultaneous outbreaks. To that end, a study by the Extension Disaster Education Network concluded that, even with a swift and effective reaction to an outbreak, up to 23.6 million animals could be lost in one attack.

Pathogens such as viruses, bacteria or fungi could be used in such an attack. Weaponisation of FMD, rinderpest or swine fever could see intensified and more targeted outbreaks of the diseases than we’ve seen in the past. History has also seen the development of more innovative means of committing such attacks, such as in WWII when British forces developed five million ‘‘cattle cakes’’ using with anthrax spores, which were to be dropped on German pastoral land.

Biological agents that affect livestock or poultry are more readily available and difficult to monitor than agents that infect humans. However, vulnerability has been reduced due to the development of Differentiating Infected from Vaccinated Animals (DIVA) vaccines during the past 10 to 15 years. The vaccines have strengthened the response to intentional animal disease outbreaks. However, while this has reduced vulnerability to agroterrorism, it hasn’t provided immunity – the ongoing outbreak of swine fever in Asia is said to be the biggest animal disease outbreak we’ve ever had on the planet and experts suggest there is no way of stopping its spread.