Unbroken cycle: Kidnapping dynamics in Nigeria

In late July and early August, bandit groups kidnapped more than 150 people in Zamfara State in a series of mass abductions, the latest indication that Nigeria’s kidnapping crisis shows no sign of easing. The country’s ongoing economic hardships, including rising living costs, have reinforced the perception of kidnap for ransom as a lucrative enterprise in an otherwise struggling economy, while also reshaping its dynamics. For example, ransom demands have climbed in response to the naira’s devaluation. At the same time, the government’s inadequate response and the growing normalisation of kidnapping have emboldened groups to adopt increasingly brazen tactics. What was once an opportunistic exploitation of security gaps has, for many, evolved into a more sophisticated and deliberate strategy for sustaining their operations.

Lay of the land

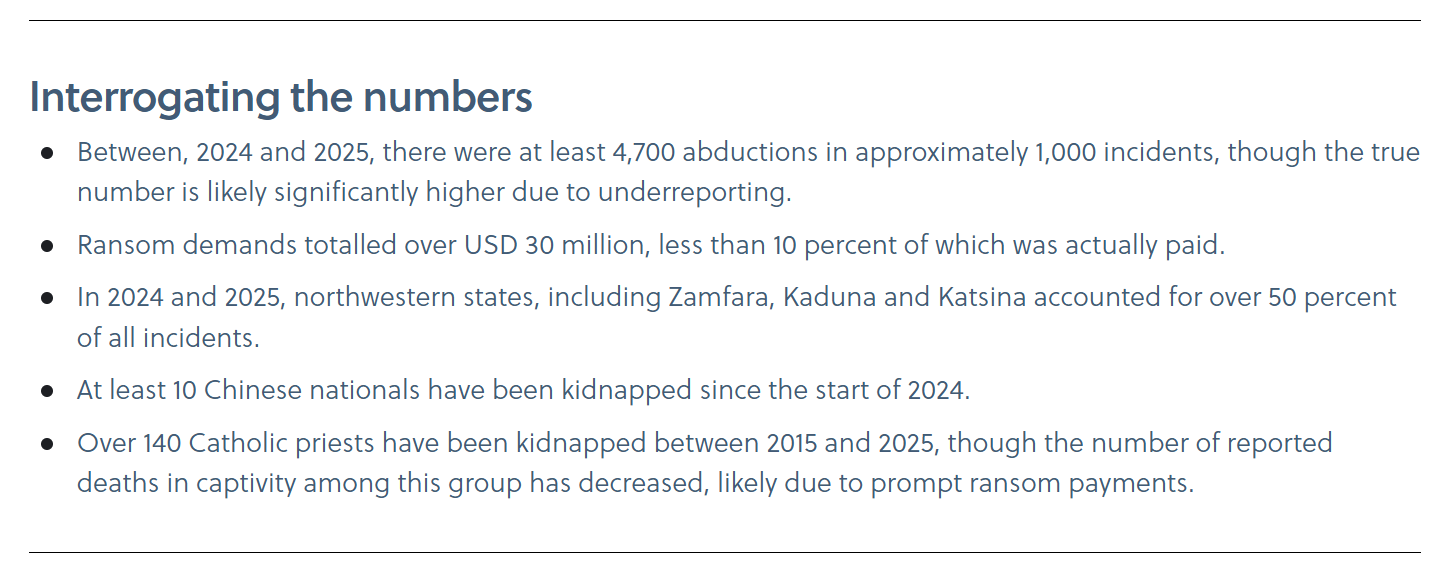

For years, Nigeria has been one of the world’s kidnap-for-ransom hotspots, with a wide range of perpetrators operating across the country. Bandit groups dominate in the northern and central regions, Islamist militants remain entrenched in the northeast, and Biafran separatist factions are active in the southeast, while gangs in the south and southwest contribute to a smaller share of cases. Most victims are local residents, with mass kidnappings occurring predominantly in remote areas of northern states such as Zamfara, Kaduna, and Katsina. However, employees of local and foreign companies have also been targeted, including Chinese nationals working on construction projects in the Middle Belt, who have faced sporadic abductions in recent years. Members of the Catholic Church have likewise been affected, particularly in the northeast, with some cases also reported in the southeast. While kidnappers sometimes pursue broader objectives, such as securing prisoner releases, attracting media attention, or undermining government authority, the principal motivation remains financial gain as the practice becomes a crucial pillar of the Nigerian illicit economy.

All about the money

One of the key dynamics shaping Nigeria’s kidnapping landscape is the country’s ongoing socioeconomic strain. Amid acute financial pressures driven by rising debt, declining oil revenues, and persistent governance challenges, the government introduced a series of reforms in 2023 and 2024. These included scrapping fuel subsidies and devaluing the naira, which dropped from NGN 450 to the US dollar in June 2023 to NGN 1,600 in January 2024. The measures have fuelled stubbornly high inflation, now above 20 percent, and driven up living costs, compounding long-standing issues such as poverty and unemployment.

Against this backdrop, kidnap for ransom has become an increasingly entrenched and profitable enterprise within an otherwise struggling economy. Established groups have grown bolder, while the financial incentives continue to draw new recruits into their ranks. Economic pressures have also shaped ransom dynamics: while demands denominated in US dollars have remained relatively static, requests in naira terms have surged in recent years due to the devaluation of the currency. This has left many families and local employers unable to meet escalating demands, forcing kidnapping groups to strike a delicate balance between overpricing and ensuring that abductions remain profitable.

Escalating audacity

The growing impunity of kidnappers has also fuelled new and increasingly dangerous tactics. Nigeria’s security and intelligence services continue to struggle with chronic problems such as underfunding, corruption, and weak legislation governing responses to kidnapping. These shortcomings have reinforced the perception among kidnapping groups that the crime is 'low risk, high reward,' encouraging more brazen methods. For example, individuals delivering ransom payments are increasingly being targeted and kidnapped themselves, with gangs collecting the original ransom and then issuing fresh demands for the new victims. In other cases, hostages have been killed after ransom payments were made or further demands issued even after the initial payment was secured.

Looking ahead

With kidnap for ransom driven by a complex interplay of factors, there is no quick solution. Even if Nigeria’s slowly recovering economy eventually delivers improved living standards, greater job opportunities, and reduced poverty, the absence of a coordinated and effective security response will leave little incentive for armed groups to abandon the practice, which has become an increasingly reliable source of revenue. In the near term, kidnapping appears caught in a self-sustaining cycle: prevailing socioeconomic pressures and weak security capacity have allowed the crime to evolve into a more sophisticated and lucrative enterprise, making it harder for overstretched agencies to contain and further emboldening the groups involved.