Muzzling the media in Ethiopia's conflict zones

On 22 February, police arrested French journalist Antoine Galindo in Addis Ababa along with his interviewee Bate Urgessa, the spokesperson of the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) opposition party. Authorities accused Galindo - who was in the country to cover the coinciding African Union Summit - of being part of a “conspiracy to create chaos.” Although Galindo was subsequently released on 29 February, his detention generated considerable international scrutiny as it marked the first arrest of a foreign journalist in the country in more than three years. Amid a wider trend of the government clamping down on dissent in the country, facilitated by an ongoing state of emergency and associated stringent laws, Galindo’s arrest is a stark reminder of the threat to journalists as well as opposition voices and human rights activists operating in or commenting on Ethiopia’s conflict zones.

Hypersensitivity in Oromia

The arrest of Galindo and Urgessa reiterates the difficulty of reporting on the highly sensitive and protracted Oromo conflict between ethnic Oromo militias and the Federal Government of Ethiopia. The failed attempts to broker peace in Oromia in 2018 and 2023 has coincided with an increased crackdown on journalists who report on the OLF and its breakaway military wing – the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA), putting them in a difficult position of navigating between providing accurate, fair reporting and avoiding government reprisal. Covering issues related to the OLF and the OLA, which remains engaged in a low-level insurgency, now runs the risk of fuelling perceptions of sympathising with the group or indeed opposing the Ethiopian government. Journalists who cover incidents involving the OLF and OLA or, as demonstrated by Galindo’s arrest even engage in conversations with members of these organisations, face the threat of arrest and broadbrush accusations of inciting unrest or supporting terrorism.

The arrest of Galindo and Urgessa reiterates the difficulty of reporting on the highly sensitive and protracted Oromo conflict between ethnic Oromo militias and the Federal Government of Ethiopian.

Censorship in Tigray and Amhara

The operating environments for journalists in Tigray and Amhara are equally precarious. During the conflict between the Ethiopian military and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) in 2020-2022, at least 63 journalists and media workers were arrested. Two journalists are also suspected to have been killed over this period. The government specifically clamped down on journalists and media outlets that were perceived as sympathetic to the TPLF or critical of the government’s actions in the region. While foreign journalists were not as severely impacted when compared to their local counterparts, this was in large part because their entry into the region was heavily restricted by the authorities. Journalists in Amhara experienced similar treatment. In May 2022, for example, authorities arrested at least 19 journalists during mass raids when Fano, an ethnic Amhara militia group which fought alongside the Ethiopian military in Tigray, began to turn against the federal government. After major clashes between Fano and government forces in April 2023, at least 11 journalists were detained for reporting on the situation; they faced an array of “anti-state” and other undisclosed charges. Four of those journalists were held in detention for several months before charges were formally filed against them.

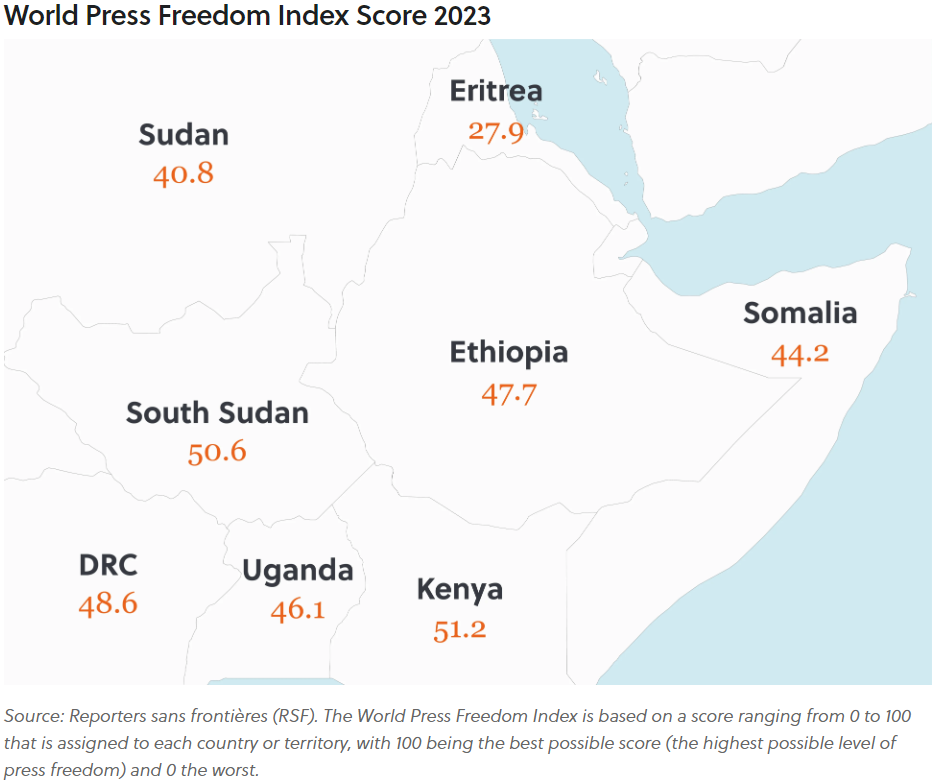

In 2023, the US-based Committee to Protect Journalists advocacy group designated Ethiopia as the second-worst jailer of journalists in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Difficult path ahead for media workers

Although media censorship is not a new phenomenon in Ethiopia, there had been a sense of optimism among many observers that the leadership of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2019, would pave the way for greater political and press freedoms in the country. However, ethnic and political divisions as well as armed conflicts have culminated in increased government clampdowns against journalists, under the purported banner of national security interests. With the tensions between the Federal Government and the OLF, TPLF and other non-state groups persisting, the threat of arbitrary detention for journalists, particularly in conflict-ridden areas, is here to stay. Although local journalists will remain at the forefront of the wrongful detention threat due to their continuous presence and active involvement in these regions, the case of Galindo underscores that foreign journalists are far from exempt.