Divestment and diplomacy: Israel’s strategic calculations under increasing international pressure

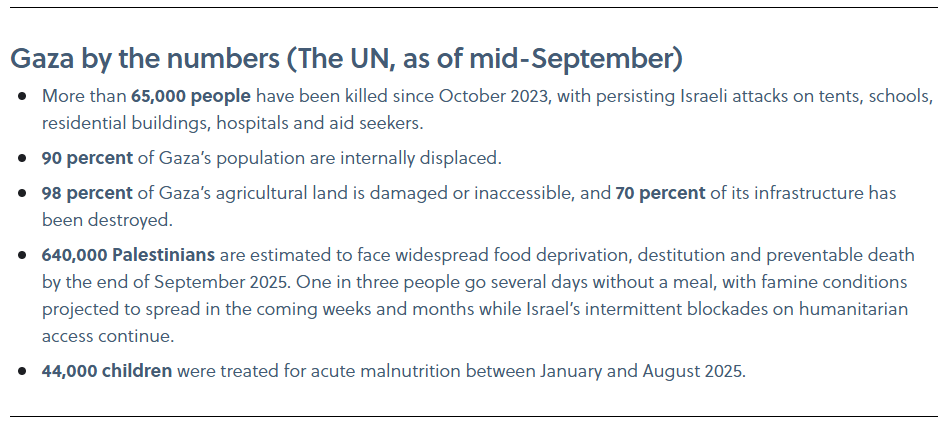

Long a state accustomed to backing from powerful allies, Israel now faces a rising tide of global criticism over its military campaign in the Gaza Strip. With Israel’s military operation against Hamas reaching the two-year mark this October, several developments in recent months – including Israel’s military offensive to occupy Gaza City, the declaration of famine conditions in the territory, and Israel’s attack on Hamas’s headquarters in the heart of Doha – have led to a stronger response from some of Israel’s closest allies. 10 Western countries, including Australia, France, Portugal, Belgium and Canada, recognised Palestine as a state – either in full or in part – during the UN General Assembly (UNGA) in late September, joining others (Ireland, Norway and Spain) that had taken the step a year prior. Germany, too, one of Israel’s most stalwart defenders in Europe, has wavered under increasing public and political pressure to reassess its position. While still reluctant to support stronger measures like EU-wide sanctions, Germany has shown an increasing willingness to criticise Israel’s actions in Gaza and the West Bank.

The most notable diplomatic pressure, however, has come from the US. Provoked by Israel’s September strike on its ally, Qatar, and wary of Israel’s increasingly isolated position on the global stage, the US has taken an increasingly firm stance towards its longtime ally. On 3 October, the US demanded that Israel end its war in Gaza and that Hamas release the remaining hostages, and has pushed both sides to agree to a 20-point ceasefire agreement. Public opinion has noticeably shifted in many countries too; in the US, disapproval of Israel’s actions in Gaza has become increasingly open (from both sides of the political aisle), and in Europe, Australia and New Zealand, tens of thousands of people have joined successive marches in recent months, demanding an end to the war in Gaza.

Pressure on the private sector

The recent statements in the UNGA are largely symbolic – with formal recognition of Palestinian statehood requiring approval by the UN Security Council, which would certainly be vetoed by the US – and it remains highly uncertain if these latest talks will facilitate long term peace. But these moves nevertheless signal a significant shift in global attitude that could cause challenges for some commercial operators. Israeli and Israeli-linked companies are facing increasing scrutiny, regulatory barriers, and cuts to funding streams from foreign governments, with particular scrutiny on those with links to Israel’s defence, construction, finance and technology sectors. To date, only a few Western countries have altered course in terms of official foreign policy, but they are nevertheless notable; Spain has imposed an arms embargo on Israel, and banned ships and aircraft carrying fuel and weapons to Israel from calling at Spanish ports or entering its airspace, for example, and Scotland has suspended government funding for any defence contractors connected to Israel’s military.

Some private banks and investment funds, too, are re-evaluating their stance on Israel. In June, for instance, Norway’s largest pension fund broke ties with two companies – one US and one German – that sell equipment to the Israeli military. Weeks later, Norway’s sovereign wealth fund followed suit, divesting its stake in a major US machinery manufacturer and five Israeli banks, over concerns around those companies’ “serious violations of the rights of individuals in situations of war and conflict.” Pro-Palestine activism presents a further concern for companies, with barricades and encampments at universities across several countries, and blockades and vandalism targeting commercial companies, over demands that institutions cut ties with Israel.

Limits of external leverage

The extent to which international pressure – and subsequent commercial disruptions – might affect Israel’s strategic security calculations, however, remains uncertain. Israel has won undeniable momentum in its security objectives over the past year, having severely eroded both Hamas in Gaza and Hezbollah in Lebanon, destroyed nuclear and military facilities in Iran, expanded its buffer zone into Syria, and struck the Houthis’ leadership in Yemen. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu further faces significant pressure from his right-wing coalition partners to pursue this line of foreign policy. Additionally, despite recent US success in bringing Israel and Hamas to the negotiating table, the two sides remain diametrically opposed in their objectives, and it remains unclear to what extent the US would be willing to utilise stronger leverage, such as reducing military support, to ensure sustained, long term progress. Scrutiny on international business ties to Israel will therefore surely continue, and perhaps ramp up in the coming months, in reaction to further developments in the Middle East. But cuts in funding, divestments, sanctions, and other punitive measures are likely to remain uneven and limited while most Western countries tread a careful line between value-based considerations and their geopolitical alliances.