When lifesavers' lives are at risk: Growing threat to aid workers in Sub-Saharan Africa

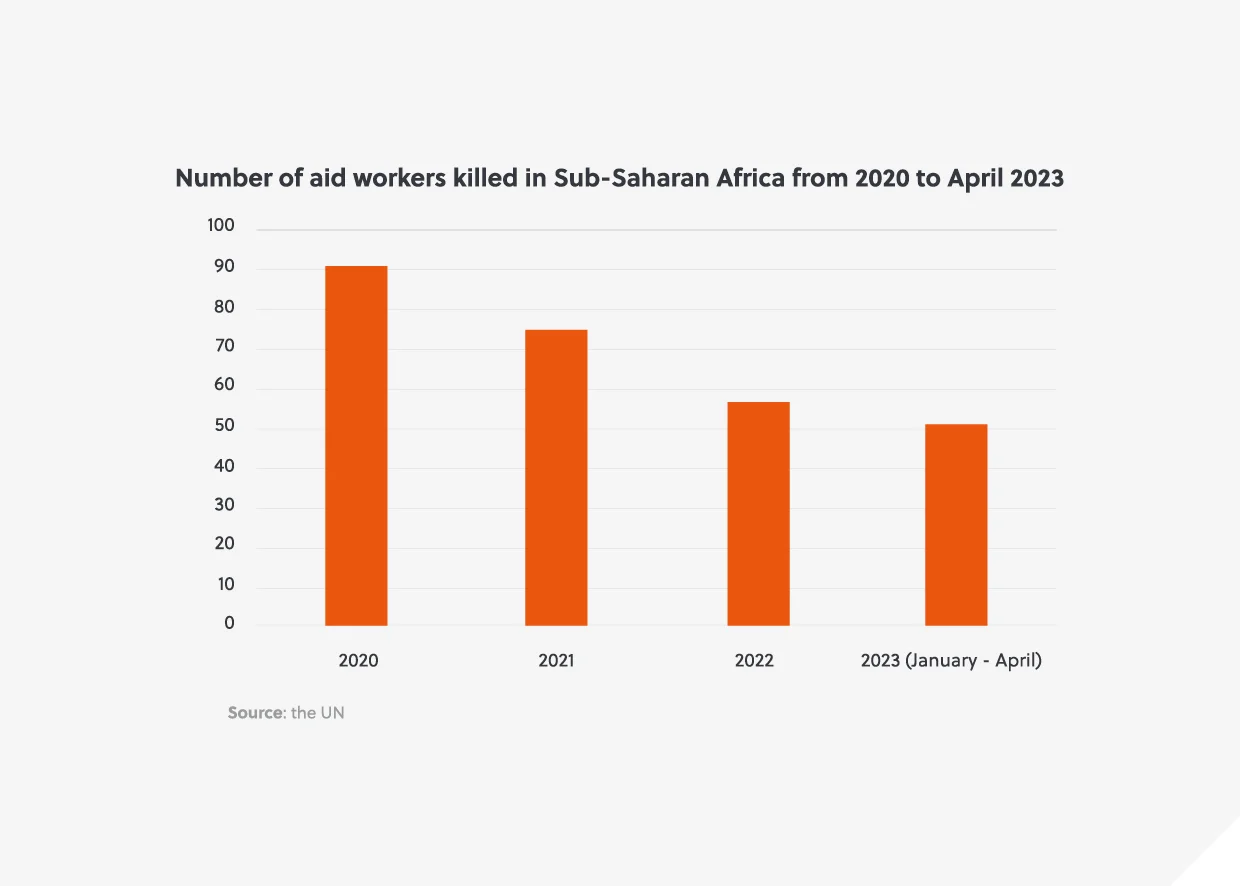

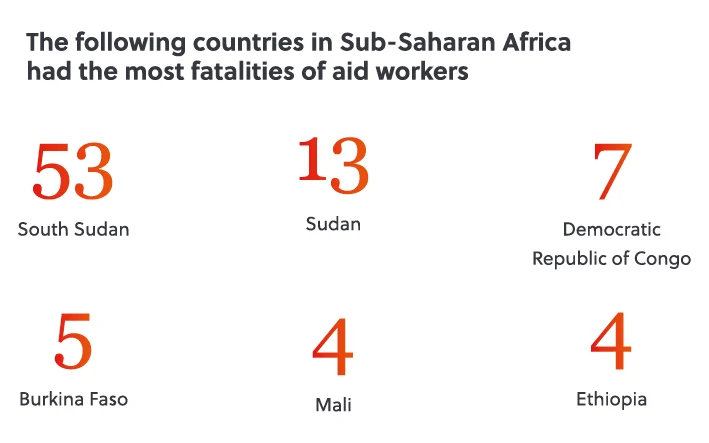

In the first four months of 2023, 51 aid workers were killed in Sub-Saharan Africa, compared to 57 victims in the whole of last year – a worrying trend for humanitarian organisations and those who are most dependent on their services. Operating in some of the most dangerous countries in the world, aid workers are targeted by rebel groups, terrorists and criminal elements driven by their narrow political, security and financial objectives. In South Sudan, for example, the failure of the 2018 peace agreement between the central government and multiple rebel groups is sustaining the longstanding civil war. Armed groups regularly attack humanitarian workers and organisations, often for cash, food supplies or other aid, equipment, and vehicles.

Militants also attack aid workers to undermine government authority and exert control over local communities. Burkina Faso, for example, has become the epicentre of the conflict in the Sahel, which has coincided with a rise in deliberate attacks on aid workers by Islamist militant groups. The fact that humanitarian workers operate in conflict-prone areas also means that they are often victims of collateral damage. In Sudan, for instance, the ongoing civil war between the Sudanese Armed Forces and the Rapid Support Forces have claimed the lives of many civilians and several aid workers in indirect attacks. In one incident in mid-April, clashes between the two sides in North Darfur killed three employees of the UN World Food Programme (WFP), prompting the WFP to halt operations in the country.

Below, we look at several key trends and dynamics relating to aid worker security.

1. INADEQUATE HUMANITARIAN AID

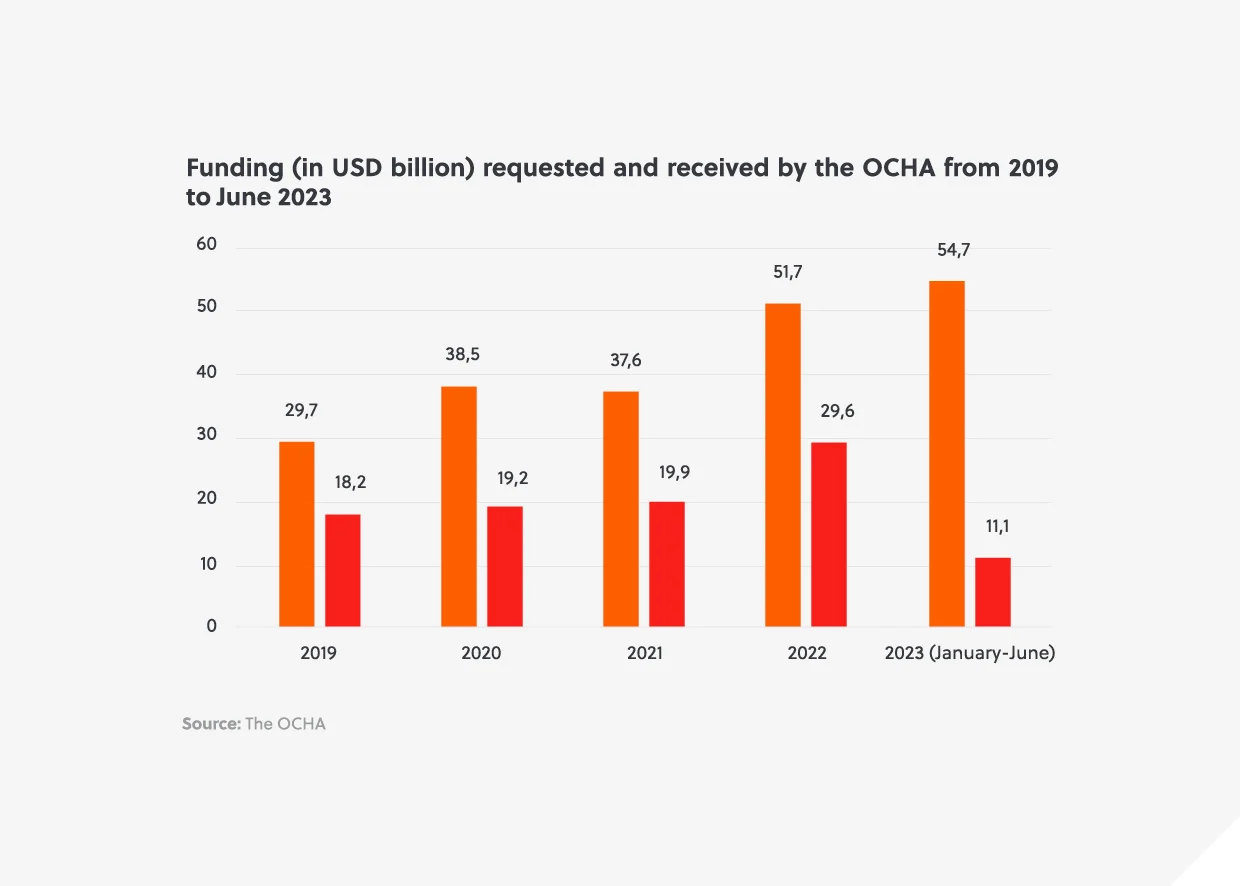

Each year, the UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) makes an appeal to donor countries and organisations for funding. The OCHA requested an unprecedented USD 54 billion for 2023, to help a record 349 million people in need. However, the OCHA typically never receives the amount of funding it requests, while high inflation and other pressing domestic challenges have contributed to several countries (such as the UK, Norway and Sweden) reducing or planning to reduce their foreign aid budgets. In fact, despite the dire humanitarian situation in many parts of the world, in 2023, the OCHA is at risk of reporting the highest percentage of unmet funding. This will not only affect people who are desperately in need of aid, but also create conditions for militant or extremist groups to exploit community grievances, potentially further worsening the security situation in places in which aid workers operate.

2. KILLING OF AID WORKERS

The number of aid workers killed in Sub-Saharan Africa 2023 will highly likely surpass the 2022 figure. While armed conflict has de-escalated in Mozambique and Ethiopia, for example, it has intensified in Sudan, Burkina Faso and the Democratic Republic of Congo. There is also no indication of an imminent de-escalation in South Sudan, where 29 aid workers were killed in the first four months of 2023.

3. ABDUCTION OF AID WORKERS

The considerable increase in the abduction of aid workers in 2022 compared to the previous year is a major concern for humanitarian organisations. Although 2023 appears to be a comparatively better year, abduction trends are difficult to predict, especially in conflict-prone countries. With limited opportunities to target foreign nationals, who are usually targeted for ransom or propaganda purposes, local aid workers remain the overwhelming majority of victims in the region. In most cases, intimidation, rather than ransom, is the primary objective of behind such kidnappings.

MOST VIOLENT COUNTRIES FOR AID WORKERS

Data collected by the UN shows that from January 2022 to April 2023, approximately 148 aid workers were killed around the world, of which more than 70 percent were killed in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Case study: Abduction of aid workers in Mali

There has been a considerable increase in the abduction of aid workers in Mali since 2017, with almost 60 percent of incidents taking place in the Mopti Region, which is the centre of the Islamist insurgency. In most cases, militant groups abduct humanitarian workers for 1-30 days over various grievances or efforts to establish authority over local communities. Kidnap for ransom incidents are rare, and are usually directed against foreign nationals or employees of major humanitarian or donor organisations. In 2022, the Malian government backed by the Russian private military company Wagner Group, launched, launched a new offensive against rebels, which has not only deteriorated the security situation but also made it more difficult to negotiate the release of aid workers in custody. More recently, in mid-June 2023, the Malian government called on the UN to withdraw its 13,000-strong peacekeeping force from the country, with rebel groups warning that their departure will pose a significant threat to peace and stability in the region. The withdrawal of UN peacekeepers will expose aid workers to greater violence and uncertainty.