Unintended consequences: Is Russia's aggression driving Nordic NATO expansion?

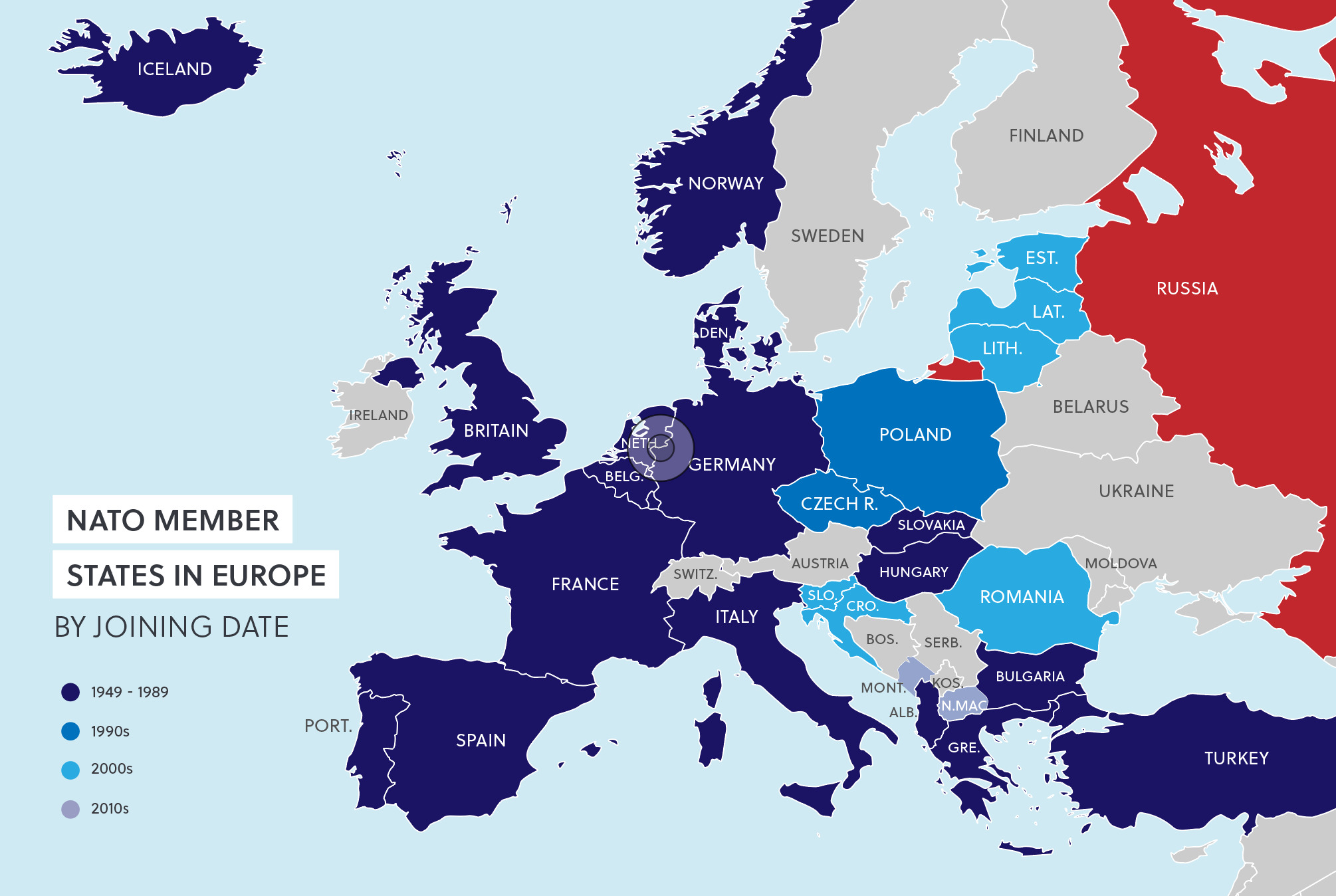

NATO’s expansion in Europe looks set to gather pace. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has prompted Sweden and Finland to reconsider their positions of military non-alignment. In fact, very few European countries – particularly those who share a border with Russia – remain outside NATO. With Belarus firmly on Russia’s side, and Ukraine at war with Russia, the delineation of Europe into rival camps appears to be solidifying.

A BIG SWING

Russia’s willingness to adopt increasingly risky strategies to counter perceived security threats at its borders has pushed European countries, including historically neutral Finland and Sweden, to bolster their defences. For the two Nordic countries, NATO membership is increasingly seen as the best route to protect themselves from future Russian aggression. In practice, both countries are already about as close to NATO as they can be without being full members. They actively cooperate with NATO across a range of initiatives, and both are Enhanced Opportunity Partners under NATO’s Partnership Interoperability Initiative (PII). But full membership, with the benefits and obligations it brings, would be a momentous change in the security policies of both countries.

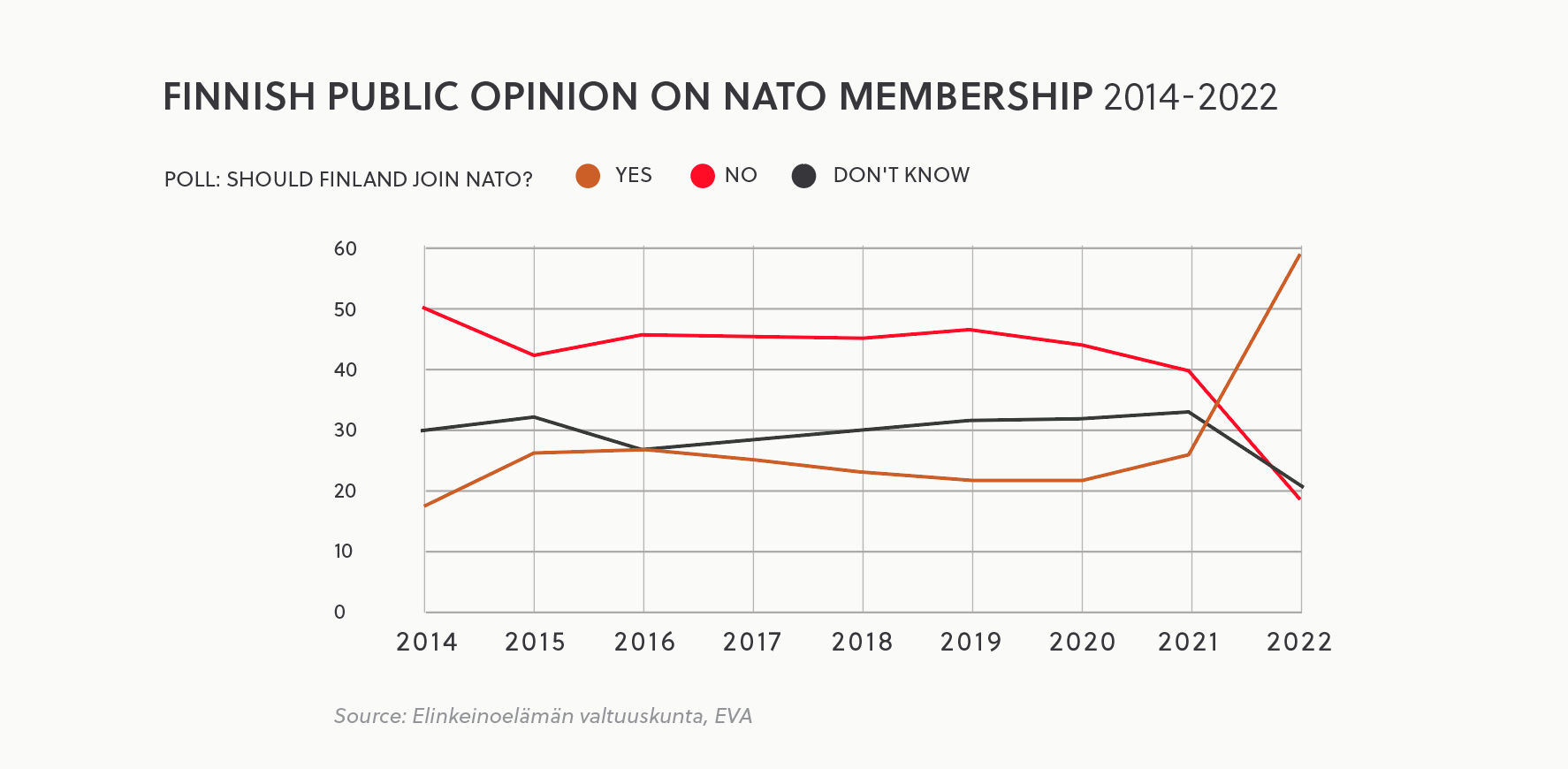

Finnish popular support for NATO membership has seen a dramatic about-turn, with the latest polling showing 60% of Finns in favour of accession to the alliance, and only 19% opposed to it. As recently as the autumn of 2021, 40% of Finns were opposed to joining, with 26% in favour. New polling in April shows that in Sweden, too, a majority now support NATO membership, with 51% of respondents in favour of joining, rising to 64% should Finland apply at the same time.

FINLAND: A DONE DEAL?

Finland’s former Prime Minister, Alexander Stubb, has been a vocal critic of Russia’s aggression, and now sees Finland’s joining of NATO as an inevitability: “The train has left the station. Finland is moving towards full NATO membership.” Most sitting Finnish politicians, including current Prime Minister Sanna Marin, have understandably been more circumspect in their public assessments, choosing instead to let parliamentary procedures run their course. The deliberative approach reflects the institutional culture of Finland, but hints also at due caution being applied in a country that shares a 1,300 km border with Russia.

Finland has worked to maintain amicable ties with its eastern neighbour since the end of World War II, more out of pragmatic than ideological consideration – Russia is a significant export market for Finland, but a wariness borne out of experience remains. The Soviet Union’s invasion of Finland during the war – under pretexts not entirely dissimilar to those Russia employed in its invasion of Ukraine – is still firmly ingrained in popular memory. And while Sweden has steadily scaled back its military spending since the 1960s – even temporarily ending mandatory conscription between 2010 and 2018 – Finland has retained a sizeable reservist force of close to 900,000 troops, and consistently maintained a relatively higher GDP share on military spending.

How much of the rapid shift in public opinion over the NATO question can be explained by Finland’s historic experience, as opposed to the dictates of the realpolitik of the day, is unclear. Either way, both among the political leadership and the general public there is now a diminishing minority who hold reservations about NATO membership. But even if the metaphorical train is headed in that direction, Finland’s accession to NATO will not be immediate – on the one hand, the Finnish government will want to ensure a solid parliamentary mandate before taking any formal steps, and on the other, they will also want to get at least implicit assurances from all current NATO members that their application would be approved. NATO member countries all hold veto power over new members, and Finland would find itself in a geopolitically precarious position should it apply to join and be rejected.

SWEDEN: ONLY FOOLS RUSH IN?

Sweden has not fought a war for more than 200 years. Unlike Finland, it does not share a land border with Russia, and the impetus to counter the Russian threat has historically been less acute. This is not to say Sweden has been complacent to the realities – for instance, in response to the Russian troop build-up ahead of the Ukraine invasion, Sweden deployed troops to the island of Gotland in the Baltic Sea. But the instinct for defaulting to neutrality runs deep, particularly within the ruling Social Democratic Party. Still, Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 appeared to rekindle Sweden’s interest in strengthening its military capabilities, with the case further bolstered by the invasion of Ukraine. This has, for instance, now prompted the editor of the Aftonbladet, one of Sweden’s biggest daily newspapers, to admit the paper has changed its editorial position to favour NATO membership, albeit “a little reluctantly”.

Much was made in the Swedish press of Marin’s visit to Stockholm in mid-April, in which she appeared to be courting her counterpart Magdalena Andersson and her government to join Finland in its NATO bid. Sweden will be completing a security policy review before the end of May, and Andersson is duly waiting for the outcome of the review before making a formal decision. But for Sweden as well as for Finland, a simultaneous application for membership would be advantageous. Were Sweden to refrain from a membership bid, it would be isolated as the only Nordic country, and only country on the Baltic coast, outside NATO. It would also, to a degree, place Finland in a strategically more difficult position as a key frontline state.

STANDING FIRM

For Russia, Finland and Sweden’s NATO membership would be a blow, if not militarily, then at least in terms of its capacity to project power internationally. A concerted bid to undermine the process is already underway: both in terms of official Russian rhetoric warning of dire consequences, as well as attempts to influence proceedings through subterfuge, such as directed cyberattacks and military posturing. These are unlikely to weigh much – the Nordic states have made it clear that they, and they alone, will be the deciders in this matter.

The formal approval process in individual member states varies, and in practice this means Finland and/or Sweden’s entry to the alliance will take anything between 4-12 months to be ratified. The interim period between applying to join and being accepted arguably opens them up to further Russian aggression. While the Nordic states have effectively shrugged off Russian threats over the matter, they will still be wary of provoking Russia without some assurances that they would not be left alone in the time between the membership application and full membership. Formally, NATO cannot extend security guarantees to non-members, but given that it would be in NATO’s own interest to support prospective members, it is likely that certain deterrent measures would be put in place to dissuade external interference to the process. To this end, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg has suggested NATO would “find ways to also address the concerns”.

Russia’s foray into Ukraine has come at a great cost to Ukraine, to Russia, and to the world. Sanctions and other isolating mechanisms against Russia are unlikely to be rolled back for some time to come. But from Russia’s perspective, Finland and Sweden’s accession to NATO might prove to be one of the more significant long-term consequences of the war. And one that Putin would almost certainly not have anticipated.