Polls under pressure: Political stability concerns in Malawi, Tanzania and Cote d’Ivoire’s upcoming elections

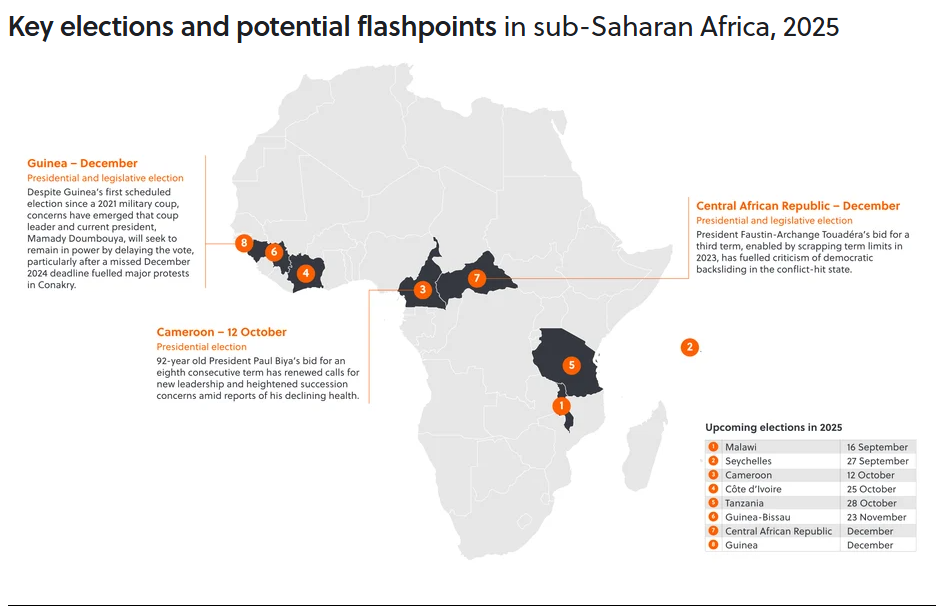

The remaining months of 2025 will be a busy election period in Sub-Saharan Africa, with voting across the region taking place amid increasingly restrictive political climates where incumbents and, in some cases, military juntas are looking to tighten their grip on power. In Côte d'Ivoire, Malawi and Tanzania, resistance has grown in response to perceived democratic backsliding, which has involved crackdowns on opposition groups, activists and candidates. In Malawi and Côte d'Ivoire (the latter of which has struggled with peaceful transitions of power since 1995), this has driven violent unrest that could intensify ahead of and after the polls. Despite continued investor optimism driven by some business-friendly reforms and signs of positive growth, these three countries also face questions over the potential for political dynamics to drive a decline in wider political, social and regulatory stability in the coming years.

Côte d’Ivoire

History repeats itself?

With 83-year-old incumbent President Alassane Ouattara seeking a fourth term in October, Côte d’Ivoire’s pre-election climate is marked by deep public disillusionment. Despite low approval for the ruling Rassemblement des Houphouëtistes pour la Démocratie et la Paix (RHDP), Ouattara remains the overwhelming favourite after four prominent opposition candidates, including former President Laurent Gbagbo, were disqualified. This has triggered regular demonstrations in Abidjan in 2025 against the government, the Electoral Commission and the judiciary, including in August. Tensions are further fuelled by the political elite’s ongoing efforts to entrench their power, exemplified by the removal of presidential term limits in 2016. With precedent for election violence – as in 2020 when Ouattara’s controversial third term bid sparked clashes and casualties – unresolved issues drive political and ethnic tensions that threaten to again devolve into potentially violent unrest in the upcoming election period.

While the Ouattara administration will likely remain in place, and Côte d’Ivoire’s economy is expected to sustain steady growth, political grievances are poised to persist beyond the election. Of concern is the age of Ouattara and senior RHDP leadership, whom opposition parties and civil society increasingly criticise as out of touch in a country where over 75 percent of the population is under 25. This has fuelled sentiment among some online “pan-African” influencers who have lauded Burkina Faso’s interim president Ibrahim Traoré, a former military officer who has advocated for a more nationalistic economic agenda, and have criticised Ouattara’s pro-Western posture. Significant uncertainty persists over the direction a successor may take in terms of political and economic reforms, and whether they will continue the current administration’s – and wider region’s – pursuit of stronger autonomy over resources and security, particularly as French troops withdraw from the country. With the potential for continued tensions over the country’s political trajectory, unrest and instability will remain a concern in the longer term.

Malawi

Broken promises, fraying patience

Malawi’s 2025 general election takes place amid acute economic strain and political turbulence, with the optimism for reform that followed the 2020 transfer of power from Peter Mutharika to Lazarus Chakwera having largely dissipated. Inflation hovers around 30 percent, driving unrest in major cities, while corruption and high unemployment remain unaddressed. Politically motivated violence has escalated since 2023 and has intensified in the run-up to the election, including attacks on protesters, opposition campaigners, and civil society leaders by assailants with suspected ties to the government. In June 2025, dozens of suspected youth militia members linked to the ruling Malawi Congress Party (MCP) attacked and injured activists during anti-government demonstrations in Lilongwe over alleged bias by the Malawi Electoral Commission (MEC) in its handling of the electoral process.

With trust in institutions such as the MEC eroding, and the prospect of a close contest growing as Mutharika emerges as a major challenger and Chakwera’s polling weakens, the MEC’s ability to deliver credible results will face scrutiny. Any disputed outcome risks triggering post-election unrest in an already volatile setting. Looking beyond the polls, entrenched institutional weaknesses will likely prevent meaningful reforms to address persistent economic challenges or political tensions, further raising the likelihood that public discontent and unrest will continue into 2026.

Tanzania

Old habits die hard

After rising to power in 2021, incumbent president Samia Suluhu Hassan’s initial reformist agenda has given way to more authoritarian tactics under the long-ruling Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) party. Though public opinion had been positive early into Hassan’s tenure due to rolling back the former administration’s ban on opposition rallies and media censorship, many of those reforms were functionally undone leading up to the 2024 local elections, which saw hundreds of arrests, and allegations of violence and extrajudicial killings of opposition supporters. The pre-2025 election atmosphere has been fraught as opposition rallies were once more banned, activists detained, and over 370 members of the main opposition party, Chama cha Demokrasia na Maendeleo (Chadema), arrested. Now, with key opposition candidates from Chadema and Tanzania’s second-largest opposition party barred from participation, and the remaining opposition too fragmented to field a viable candidate, CCM and President Hassan are almost certain to maintain their positions in October.

While widespread, disruptive unrest is unlikely during the election due to the government’s strong-handed suppression of opposition, internal factionalism and power struggles within the ruling CCM party will continue to shape the political landscape beyond the vote. Political tensions have remained elevated during President Hassan’s tenure, as her unexpected ascension after Magufuli’s abrupt passing limited her ability to consolidate power early on. This has resulted in some policy inconsistency, with elements of Magufuli-era nationalism still championed by parts of the party. Nevertheless, broad economic indicators for Tanzania remain positive and investor sentiment remains stable. An increasingly dominant ruling party will likely continue efforts to stifle opportunity for popular resistance in the coming months, but this could, in the longer term, further erode institutional credibility and drive uncertainty in the wider political and regulatory environment.