No simple solutions: Tackling Islamic terrorism in France

On 16 October, Abdoullakh Abouyedovich Anzorov beheaded schoolteacher Samuel Paty in the Parisian suburb of Conflans-Sainte-Honorine. In the weeks preceding the attack, Paty had showed his students cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad during a class on the freedom of expression. Some students and their parents had taken exception to Paty’s actions, complaining that the images were insulting to Islam, and had filed a complaint with police and staged protests at the school. On the day of the attack, the 18-year-old Anzorov sought out Paty at the end of the school day, and after following him a short distance killed him. Police responded within a few minutes, and after Anzorov threatened them, they shot and killed him.

A HISTORY OF VIOLENCE

The nature and circumstances surrounding Paty’s murder attracted widespread attention to the seeming incompatibility between secularism in France – jealously-guarded and codified in its constitution since 1905 – and accommodating the sensitivities of Muslims offended by images such as those on display in Paty’s classroom. The underlying issue is not a new one. Perhaps the most prominent incident of this nature was the 2015 shooting at the French satirical weekly newspaper Charlie Hebdo in Paris in which 12 died and 11 were injured. Charlie Hebdo had drawn the ire of Muslims since 2006, when it first published controversial images of the Prophet. Indeed, the trial of 14 people charged with aiding in that attack started just a few weeks prior to Paty’s murder.

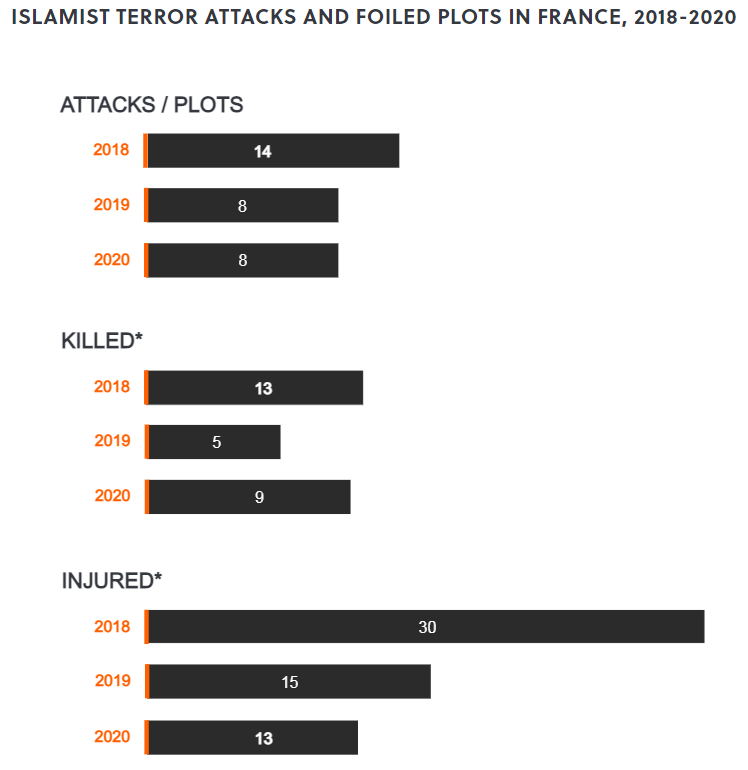

While not all are related to this specific issue, Islamist terror attacks in France have taken place at a steady rate in recent years. S-RM has recorded eight attacks or foiled Islamist terror plots in 2020 and 2019, and 14 in 2018. A total of 27 people have been killed, and further 58 injured.

Following Paty’s murder, thousands demonstrated across France to denounce the attacks. Condemnation was not only secular: on the Friday following the attack, the French Council of the Muslim Faith (CFCM) sent imams a proposed text for their sermons with the opening text: “The horrible assassination of our fellow citizen Samuel Paty… reminds us of the scourges which sadly mark our reality: that of the outbreaks, in our country, of radicalism, violence and terrorism which claim to be Islam making victims of all ages, all conditions and all convictions.” While the vast majority of French Muslims reject these incidents, many nonetheless feel they are being pushed to the margins in effectively having to choose between being French and being Muslim. Tellingly, the unemployment rate among Muslim youth in France is estimated to be four times higher than that of non-Muslim youths. While there are a number of contributing variables, it speaks to a (growing) divide within France – one that extremists on both sides are attempting to exploit. They may be succeeding: a poll in the immediate aftermath of Paty’s murder showed that 87% of respondents agree secularism is under threat and 79% feel “Islamism” has “declared war” on France.

DAMNED IF YOU DO, DAMNED IF YOU DON’T

The French government is seemingly being asked to achieve the impossible in standing up for freedom of expression, placating nationalists without emboldening the far-right, while at the same time creating a national identity that doesn’t alienate French Muslims. If the 16 October attack fell into a pattern of Islamist terror attacks in France, so did the French government’s difficulty in spelling out an effective message and response to defuse tensions. Already earlier in October, President Emmanuel Macron had come under fire over his pronouncements about Islam, calling it a “religion in crisis” and suggesting steps to “reform” Islam in France.

Macron’s domestic critics have accused him of being soft on terror, with polling suggesting just 37% of people approve of his handling of the fight against extremism. Internationally, Macron has faced even harsher criticism: Prime Minister Imran Khan of Pakistan accused Macron of “attacking Islam.” Turkish president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, said Macron had a “problem with Islam”, and suggested he “needs mental treatment.” While others may not have been quite as abrupt, leaders across the Muslim world expressed their displeasure at France’s treatment of Islam.

The French government is seemingly being asked to achieve the impossible in standing up for freedom of expression, placating nationalists without emboldening the far-right, while at the same time creating a national identity that doesn’t alienate French Muslims.

In the wake of the recent attacks Macron might have chosen some of his words more carefully, but he has been at pains to point out that it is only a minority of Muslims in France that pose a threat, and that he understands why some see the cartoons featuring the Prophet as offensive or Islamophobic. But voicing this distinction may not matter, and in some respects the damage has been done. Large protests in Bangladesh and Palestine, and a French consumer goods boycott in Qatar and Turkey point to some of the fallout from recent events. Authorities have already warned French citizens travelling to Muslim countries to adopt additional security measures in anticipation of potential backlashes. For the French government, and for French companies operating in Muslim countries, the year ahead may be challenging.

There are no simple solutions, and disputes between Europe and Muslim-majority countries such as Turkey extend beyond a debate about cartoons. France has the largest Muslim population of any European country – and that population is diverse, rather than a singular bloc with shared religious and political perspectives. While simple messages may be politically expedient in times of crisis, European governments will neither navigate their domestic challenges, not present satisfactory solutions internationally without adopting a nuanced approach. At least for the time being, the growing rift between Europe and the Muslim world is likely to remain unbridged.