Enemies of enemies turn friends: Ethiopia and Eritrea’s complex conflict

In late July, Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki accused Ethiopia's Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed of stoking conflict, particularly for amassing forces along the countries’ shared border and making claims over a portion of Eritrea to secure Red Sea access for Ethiopia. Though tensions have remained a feature of the countries’ relations, the diplomatic landscape has proven especially fraught following the Tigray War in the early 2020s, elevating concerns over a possible re-emergence of open conflict and its ramifications for the Horn of Africa. Inter-state war, however, remains an unlikely progression, with both countries instead more likely to engage in a combination of posturing, proxy conflicts and political jostling to pursue their respective goals.

Breathing new life into old enmity

The nexus of the currently elevated tensions is long-held mutual distrust between Asmara and Addis Ababa, a dynamic which has sustained their rivalry since Eritrea’s 1993 independence from Ethiopia. Their brief alliance during the 2020–2022 Tigray War – between the Eritrean government and Ethiopia’s federal forces under the newly formed Prosperity Party (PP) led by Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed – against the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) was an anomaly in an otherwise fraught relationship. At the time, both Eritrea and the PP shared hostility toward the TPLF, which had dominated Ethiopian politics for decades and was seen by Asmara as responsible for perceived and real slights against Eritrean sovereignty. After the war, the rivalry resumed, as Eritrea was further angered by its exclusion from the November 2022 Pretoria Agreement that ended the conflict, a move Asmara saw as a sharp rebuff in favour of its sworn enemy, the TPLF.

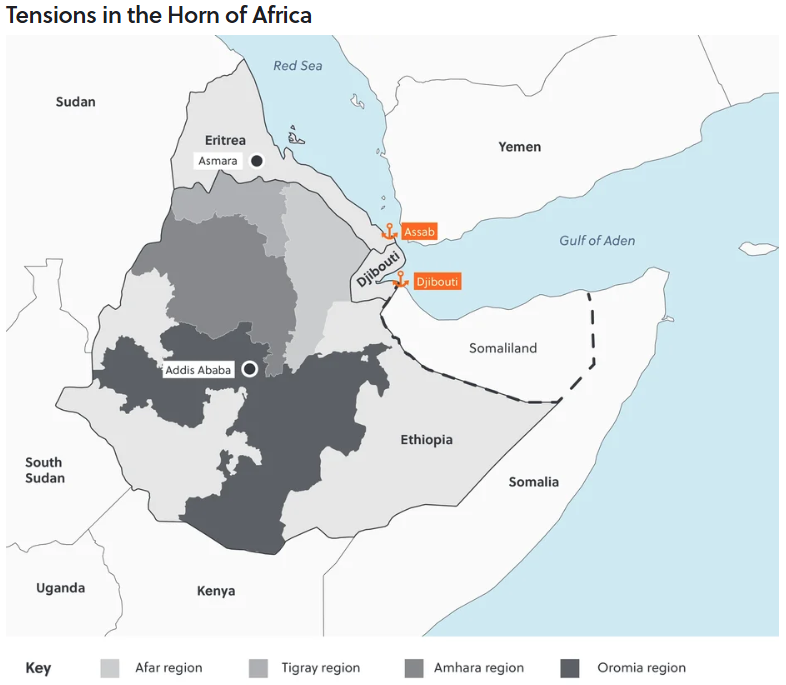

Relations have recently frayed further after Abiy signalled his intent to acquire a port for Ethiopia along the Red Sea, raising concerns over whether it might be seized by force. Reports dating back to March indicate a buildup of Ethiopian troops along the border in the eastern Afar region, positioned less than 100 km from the Eritrean coastal city of Assab. Capturing this location, which Addis Ababa has reportedly earmarked for Ethiopia’s planned Red Sea port, would likely require an open conflict. For Abiy, gaining access to the Assab port would be seen as rectifying a historical wrong following Ethiopia’s loss of direct sea access after Eritrea’s independence. Ethiopia’s ambitions have intensified recently, especially after Somalia used diplomatic and legal measures to block a port agreement between Ethiopia and Somaliland. As a result, Ethiopia remains almost entirely reliant on Djibouti’s ports, which currently handle around 90-95 percent of its trade. Asmara, however, views these moves as an existential territorial threat from its former ruler and has likewise been amassing forces near Assab. Unsurprisingly, concerns over another conflict between the two troubled neighbours have grown, particularly as such a conflict could destabilise not only Ethiopia’s already fragmented domestic landscape but the wider Horn of Africa region.

The path of least resistance

However, open conflict remains unlikely in the coming year, with proxy clashes and posturing more probable. Despite hostile rhetoric, both countries are likely to avoid interstate war due to constraints on both sides of the border. Open conflict would require military and diplomatic resources that neither can afford, particularly as Eritrea faces international sanctions and Ethiopia continues fighting a civil war in Amhara and Oromia while also grappling with significant economic challenges, including high public debt. While military buildup in Afar remains a concern, Addis Ababa’s February withdrawal from major towns in Tigray further signals a desire to avoid hostilities, at least until its plans for Assab are more feasible.

This is not to say that current tensions will simply recede. Both sides are likely to draw on their long history of supporting proxy groups to undermine one another. Asmara maintains ties to Fano militias, a loose but currently fragmented Amhara alliance rebelling against the Ethiopian government, while Addis Ababa continues to provide support and operational space to the Red Sea Afar Democratic Organisation (RSADO), an Eritrean Afar group which has accused the Eritrean government of ethnic cleansing. With both sides highly suspicious of each other’s intentions, they are likely to continue leveraging these proxies to stoke unrest and disrupt their intended targets.

A key area of concern, however, is whether these proxy dynamics could take root within the deeply factionalised TPLF, which has lost much of the organisational resilience and popular support that sustained it during the Tigray War. Factionalism has increasingly weakened the TPLF, which is now divided into two main camps: one led by Getachew Reda, president of the Tigray Interim Administration (TIA) and post-conflict authority, and another led by Debretsion Gebremichael, who rejects the TIA and controls the central and northwestern parts of Tigray. As a result, the TPLF now functions less as the unified force that fought in the early 2020s and more as a collection of competing factions, heightening the potential of internal escalation. Although these factions have yet to signal concrete alliances with either Eritrea or Ethiopia, the degree of disunity increases the likelihood that a third party could exploit the splits, or that the TPLF factions themselves could become tools in the broader proxy conflict.

No exit

There remains no clear path out of this situation, with Asmara and Addis Ababa likely to not only maintain their long rivalry, but also dig their heels in over the question of Red Sea access. Until Addis Ababa secures access to another port, Abiy’s rhetoric is unlikely to budge, driving persistent mistrust and political posturing. This dynamic, intensified by the unresolved aftermath of conflict in Tigray, will continue to sustain elevated tensions and potential for proxy conflict over the coming year as both countries remain unequipped for open conflict.