Counternarcotics in the Caribbean: The geopolitical implications of the US campaign against transnational organised crime

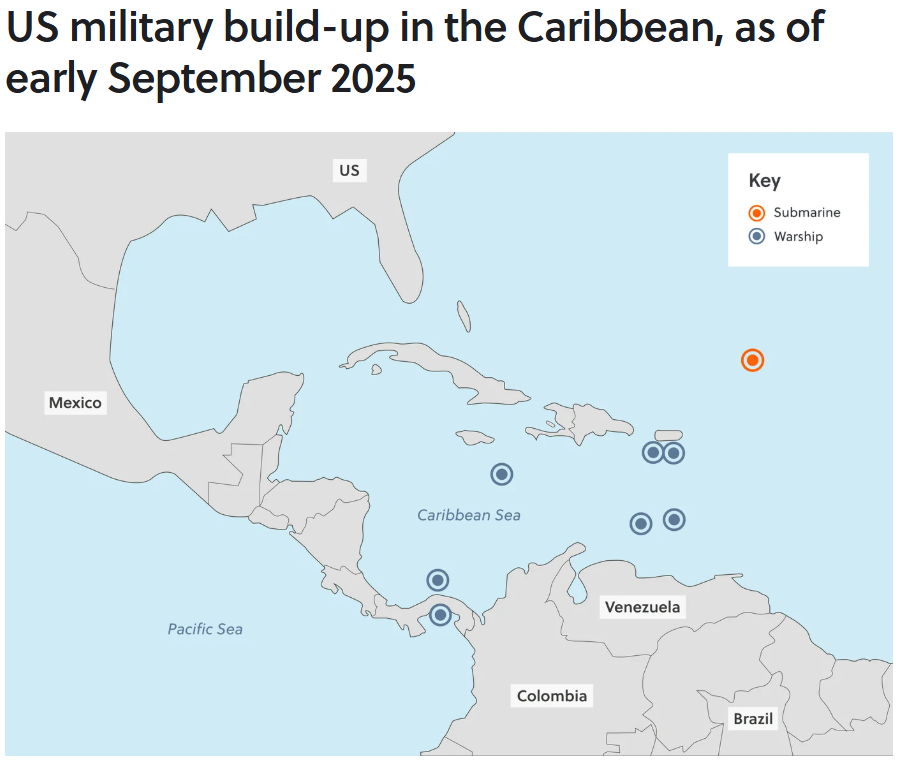

“Earlier this morning, on my Orders, US Military Forces conducted a kinetic strike against positively identified Tren de Aragua Narcoterrorists,” wrote US President Donald Trump on 2 September. The military strike reportedly killed 11 people on board a suspected drug-smuggling boat in the southern Caribbean, and two weeks later, three more were reportedly killed in a second attack on a similar vessel, setting a new precedent for US military action against the regional drug trade. The US has framed these efforts as a ramping up of its campaign against transnational organised crime, following its designation of the Venezuela-based Tren de Aragua (TdA) gang and six Mexican cartels as terrorist organisations earlier in the year. Additionally, the US deployed thousands of troops, several warships, amphibious vessels, fighter jets, drones and patrol aircraft to the Caribbean in August, reportedly accompanied by a directive authorising the use of military force on foreign soil against cartels, setting the stage for the attacks that followed. While the September strikes drew criticism and questions over their legality, they indicate a clear US intent to shift towards a policy of lethal force against these groups.

Alongside this show of force, the US administration has increased pressure on Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, declaring him the alleged head of the Cartel de los Soles crime group, designating it a terrorist organisation, and issuing a USD 50 million bounty for information leading to Maduro’s arrest. Additionally, Maduro has accused the US of attempting to provoke regime change in Venezuela through military pressure, a claim that the US administration has denied. There is significant uncertainty over the extent of Maduro’s role – or that of his government – in drug trafficking, and around ultimate US intentions in the region. Nevertheless, in either case, US military and counternarcotic manoeuvres have real repercussions for security in the region, and will pose tangible challenges for regional governments.

Security in the Caribbean

Venezuela has responded in kind to the US military deployment; Maduro has mobilised the civilian reserve Bolivarian Militia, deployed the navy to patrol Venezuelan territorial waters, banned drone flights, and sent 15,000 troops to the Colombian border. Whether the US or Venezuela intend open conflict or not, the current proximity of military forces carries with it the risk of an unintended escalation; on 6 September, for instance, Trump threatened to shoot down Venezuelan jets after they allegedly approached a US warship.

US military and counternarcotic manoeuvres have real repercussions for security in the region, and will pose tangible challenges for regional governments.

It is also unclear whether the current action will improve the efficacy of the US counternarcotic campaign. There is evidence to implicate the upper echelons of the Venezuelan government in the regional cocaine trade; including US convictions of two members of Maduro’s family in 2016, and another against Hugo Carvajal, a former high-ranking official, in June 2025. However, with most cocaine produced in Colombia, Peru and Bolivia, and trafficked via the Pacific coast rather than the Caribbean, Venezuela plays a comparatively minor role in the trade. Additionally, drug cartels are highly adaptable, and are likely to shift trafficking routes in response to new security measures. The targets of enhanced US actions so far – such as trafficking boat crews – are low-level criminals within larger organisations, and easily replaceable. As a result, it is unlikely that the latest US campaign will effectively erode these cartels’ overall operational capabilities.

Challenges facing other countries

Meanwhile, the increasing militarisation in the Caribbean, and the intensifying US focus on the region’s broader narcotics trade, will pose challenges for other regional governments. This may include military intervention within their borders, US sanctions and other punitive measures, and impacts from mass migration.

Colombia: On 16 September, the US government partially decertified Colombia as a US security partner, reflecting US frustration with the current Colombian government’s mediative approach to narcotrafficking. While the US stopped short of cutting aid or imposing sanctions, these measures remain possible if relations continue to deteriorate. In the interim, the downgrade will negatively affect Colombia’s credit and investment outlook, and will likely increase the salience of law and order issues in the upcoming Colombian presidential election.

Mexico: President Trump has, on several occasions, threatened military intervention against the cartels in Mexico, “with or without the consent of the Mexican government.” The US military has deployed nearly 10,000 troops to the border. Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum has rejected the prospect of a US military presence in Mexico, but the US is likely to continue pressuring Mexico to clamp down on cartels, including by imposing new trade tariffs, revoking visas for political leaders, and deploying targeted sanctions against Mexican financial institutions it deems to be compromised.

Brazil: President Trump and Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva have been at odds for months over the trial and conviction of Brazilian ex-president and Trump ally Jair Bolsonaro. In retaliation, Trump has raised tariffs on Brazil and imposed sanctions on Brazilian judges, although the two leaders reportedly had a positive dialogue at the recent UN General Assembly. At the same time, the US has threatened to designate the Brazilian criminal organisations Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC) and Comando Vermelho (CV) as terrorist groups, which would greatly increase compliance and sanctions risks for foreign companies operating in Brazil, given these groups’ widespread penetration of the private sector. Additionally, the military build-up in the Caribbean could cause disruptions to the Brazilian shipping sector, and security challenges in the event that Venezuela-US tensions trigger increasing immigration flows into northern Brazil.