Civic disobedience: Extortion rackets masquerading as social organisations in Indonesia

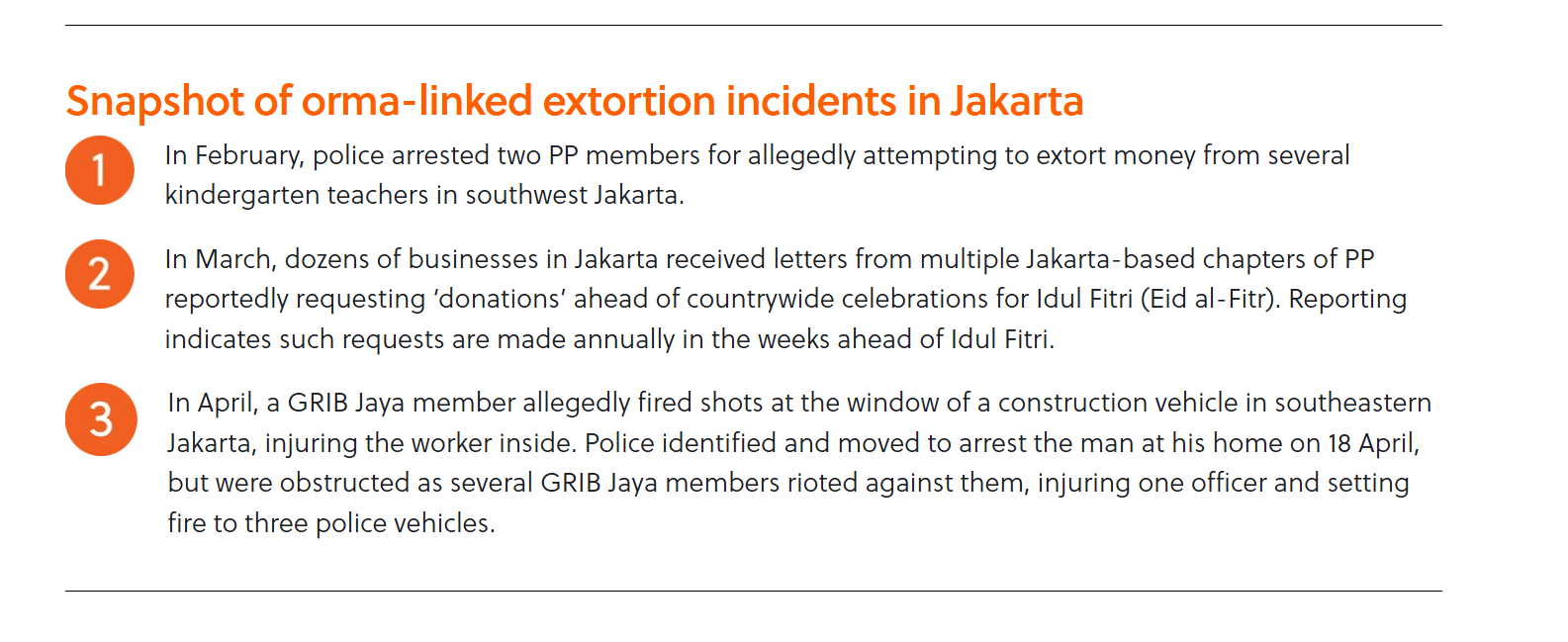

In early May, authorities launched a countrywide crackdown on premanisme (thuggery) offences, resulting in the resolution of over 3,300 related cases in the first few weeks, with extortion emerging as the most widely reported crime. Of the nearly 1,200 suspects arrested in Jakarta alone, at least 141 belonged to civic organisations (locally known as ormas), some of which have maintained a prominent role in extortion and other organised crime-related activities across Indonesia for several years. Such groups, which include Gerakan Rakyat Indonesia Bersatu (United Indonesian People's Movement, GRIB Jaya) and Pemuda Pancasila (Pancasila Youth, PP), are a minority of Indonesia’s over 550,000 civic organisations. Despite this, their operations continue to sustain accusations of cartel-like behaviour including systematic harassment and extortion, as well as inter-gang rivalries escalating to clashes over territory, underscoring the threat they pose to both commercial operations and personnel safety.

Same culprits, new routines

Though civic organisations have engaged in extortion racketeering for several years, they have drawn increased scrutiny amid a rise in violent extortion countrywide in recent months. Despite existing amid a much broader net of extortionists in Indonesia, such groups – including GRIB Jaya and PP – are of particular concern to local and foreign companies alike, notably in hotspots like Banten and West Java provinces, as well as Jakarta. Targeting a range of sectors, from manufacturers (particularly those operating in industrial zones) to public services, the widespread nature of such offences, as well as broad reach of GRIB Jaya and PP specifically, has led to many business owners treating the extortive fees as a form of corporate social responsibility. With such incidents being especially frequent in Indonesia’s business hubs, the Himpunan Kawasan Industri (Indonesian Industrial Estate Association, HKI) estimates that the country has lost out on hundreds of millions of dollars in investment due to the ormas, highlighting how the groups have given rise to a fraught operational environment for companies looking to set up shop.

While perpetrators are frequently caught during anti-organised crime operations, the quasi-legal nature of ormas’ activities enables the larger group to maintain plausible deniability. For instance, members often stage ‘protests’ – obstructing commercial operations or goods transportation – to extract protection fees from victims or secure ‘donations.' Another increasingly common tactic involves compelling companies to procure services – such as security and catering – or directly employ personnel from the ormas, with these contracts often valued in the billions of rupiahs. Additionally, ormas also continue to partake in less ambiguous forms of organised crime, such as clashes over territory, and there have been numerous allegations of targeted assault and theft, extending the threat of physical violence to individuals as well. Due to these practices, and their large numbers, ormas pose a significant threat to operational continuity and personnel safety, particularly as several of the groups’ historical extortion activities have also included violence against targeted victims.

No let up in sight

The institutional response has been mixed, with police conducting several operations targeting ormas yet often stopping short of treating them as organised crime syndicates. This is largely attributed to their quasi-legal tactics as well as links between prominent government officials and ormas’ leadership, both of which provide them with a degree of immunity from decisive government action. Consequently, the police’s response to extortion will likely continue on a case-by-case basis, allowing the broader organisations to operate in the background, able to recruit for each member it loses to the law.